Translate PaperArtículo originalPotencial de plantas aromáticas en la entomofauna y calidad del rambután (Nephelium lappaceum L.)

Francisco Javier Marroquín-Agreda [1]

Magdiel Gabriel-Hernández [1]

Humberto Osorio-Espinoza [1] [*]

Ernesto Toledo-Toledo [1]

[*] Autor para correspondencia. hosorio2503@yahoo.com

RESUMENEl rambután en el

Soconusco, Chiapas, México, alberga una superficie mayor a las 2000

hectáreas; área que aloja sistemas de monocultivos, fundamentados bajo

esquemas de insumos externos. El presente estudio se desarrolló durante

agosto 2013 - junio 2014, en una plantación de cuatro años de

trasplantada, localizada en el municipio de Huixtla, Chiapas, México;

con el objetivo de evaluar el potencial alelopático y atrayente de

plantas aromáticas sobre la entomofauna y calidad comercial del

rambután. Se evaluaron tres especies de plantas: Origanum vulgare, Ocimum basilicum y Tagetes erecta,

asociadas al cultivo de rambután; bajo un diseño experimental en

bloques al azar con cuatro tratamientos y cinco repeticiones; donde se

midieron indicadores de la abundancia, habito alimenticio de insectos y

calidad de frutos de rambután. Los resultados demostraron que las

plantas aromáticas incrementan la abundancia de insectos, con un total

de 13 481 individuos distribuidos en 13 órdenes y 87 familias; el 32,00 %

corresponde a insectos asociados a Ocimum basilicum, 30,03 % Origanum vulgare, 21,07 % al testigo y el 16,88 % a Tagetes erecta. Ocimum basilicum presentó el porcentaje más alto de insectos benéficos (2,08 %), O. vulgare (1,15), Tagetes erecta (1,11), siendo inferior el testigo (0,85 %); no obstante, O vulgare

presentó el mayor número de piojo harinoso. En la fase reproductiva

existen diferencias en las fechas de floración y antesis; donde, O. basilicum

presenta una precocidad de 17 días con respecto al sistema tradicional.

Los parámetros de calidad comercial (peso y solidos solubles) se ven

mejorados con la asociación de plantas aromáticas, principalmente con Tagetes erecta.

INTRODUCCIÓNEl rambután (Nephelium lappaceum L.) en México se cultiva en cinco entidades federativas: Chiapas, Oaxaca, Tabasco, Michoacán y Nayarit 1. El Soconusco, Chiapas, enfatiza por superar las 2000 ha 2,

superficie que se distribuye en 716 productores de esta exótica fruta;

siendo así el sistema hortícola de traspatio y el pilar económico de

numerosos núcleos familiares. Sin embargo, los métodos y técnicas

productivas se fundamenta en decisiones del control químico y bajo una

estructura de monocultivo; el cual favorece el deterioro de la

productividad y calidad del fruto, además de la incidencia de insectos,

como es el caso del piojo harinoso (Planococcus lilacinus)

hemíptero de la clase insecta, considerado una plaga; no obstante,

Estados Unidos de Norteamérica tiene esta plaga en cuarentena, afectando

con ello la exportación de frutas para países como Japón 3.

Ante el deterioro agroproductivo, incidencia de plagas en los huertos frutícolas y los resultados promisorios de Tagetes erecta sobre el crecimiento y calidad de Cedrela odorata; la asociación de especies aromáticas como el orégano (Origanum vulgare), albahaca (Ocinum basilicum) y flor de muerto (Tagetes erecta)

podrían ofrecer un potencial en la alelopatía de plagas o atrayentes de

insectos polinizadores, o bien como fitomejoradores en la calidad o

inductor floral de especies de frutales 4.

Ante esa premisa, el presente trabajo centra sus objetivos en la

evaluación del potencial alelopático y atrayente de plantas aromáticas

sobre la entomofauna y calidad comercial del rambután.

MATERIALES Y MÉTODOSLa

investigación se realizó durante el periodo productivo agosto 2013 -

junio 2014, en una parcela cultivada con rambután de 4 años de

establecida, con distanciamiento de 10 x 10 m. Ubicada en el municipio

de Huixtla, Chiapas, México, en los paralelos 15°10´23.00´´ latitud

norte y 92° 32´02.00´´ longitud oeste, a una altitud de 27 m s.n.m. Las

condiciones ambientales prevalecen con temperatura media anual de 28 °C,

mínimas de 14 °C y máximas de 42 °C. La precipitación pluvial oscila

entre los 2 500 y 3 000 mm anuales. Los suelos predominantes son del

tipo cambisol, de textura ligera franco-limoso. Durante el experimento

se evaluaron las interacciones individuales de tres especies de plantas

aromáticas (Origanum vulgare, Ocimum basilicum y Tagetes erecta)

asociadas con un sistema de producción de rambután, todas ellas en

comparación con el testigo (sin asociación). El arreglo espacial de las

especies aromáticas fue en surcos en contorno al límite exterior de área

de goteo de los árboles de rambután, con distancia de 40 cm entre

surcos y 30 cm entre plantas. Cuando las especies aromáticas alcanzaron

una altura ±50 cm se realizaron podas vegetativas con frecuencia de 15

días, estrategia para la liberación de metabolitos secundarios y

promover la producción de biomasa. Los tratamientos fueron aleatorizados

bajo un diseño experimental de bloques completos al azar, con cuatro

tratamientos (tres asociaciones + testigo) y cinco repeticiones (árbol

de rambután), en un área total de 4 200 m2.

Para

la captura de los insectos se utilizó una red entomológica de 50 cm de

diámetro, se hicieron 10 golpes dobles de red de ellas, cinco sobre las

plantas aromáticas y cinco sobre los árboles de rambután, durante el

periodo noviembre 2013 - junio 2014 (floración del rambután). La

clasificación se realizó en el laboratorio de biología de la Faculta de

Ciencias Agrícolas de la Universidad Autónoma de Chiapas, con el apoyo

de un microscopio estereoscopio digital binocular modelo ED-1805 y

claves taxonómicas 5, tomando como

referencia una guía de insectos benéficos. Se clasificó de acuerdo al

orden y familia, así como a sus hábitos alimenticios (depredadores,

parasitoides y polinizadores) (6.

Asimismo, durante el desarrollo de los frutos de rambután se realizaron

evaluaciones de abundancia del piojo harinoso y en la madurez

fisiológica visual de los frutos, se colectaron de los árboles 25 frutos

por tratamiento, a los cuales se les determinó los parámetros de

calidad: peso del fruto (g), diámetro del fruto (cm), longitud del fruto

(cm), peso del arilo (g), diámetro del arilo (cm), longitud del arilo

(cm), sólidos solubles (°Brix), pH y acidez titulable.

Los

resultados fueron analizados con el software estadístico Statgraphics

centurión versión XVI.I, con el cual se realizó un análisis de varianza

de clasificación simple y aplicación de la prueba de rango múltiple de

Tukey para los casos de significación a un 95 % de probabilidad de

error.

RESULTADOS Y DISCUSIÓNLa

abundancia de insectos hace referencia a la riqueza de individuos que

se presentan en una dimensión espacio-temporal definido, resultante del

conjunto de interacciones entre especies que se integran. La abundancia

de insectos total acumulada durante el desarrollo del experimento fue de

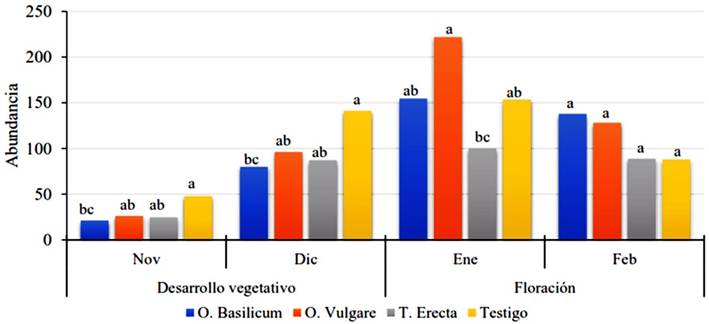

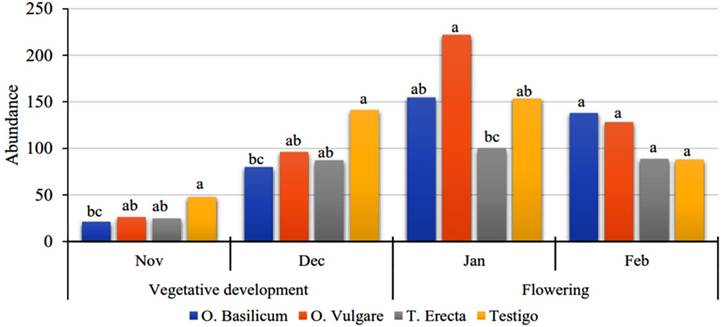

13 481 individuos en una superficie de 4 200 m2; de acuerdo con el análisis estadístico y la prueba de Tukey. Las asociaciones con mayor abundancia total fueron O. basilicum con 4 315 individuos, representando el 32 % del total de insectos colectados; O. vulgare con 4 049 (30 %) y el testigo 2 841 (21 %), comparados con T. erecta 2 276 (17 %); esta última fue estadísticamente inferior a O. basilicum (Figura 1).

*Letras diferentes presentan diferencia estadística según Tukey al 95 % de confiabilidad

Abundancia de insectos en un huerto de rambután intercalado con especies aromáticas

Las fluctuaciones de la abundancia de

insectos asociada a las plantas aromáticas, se fundamenta por ser fuente

de néctar, polen, biomasa y metabolitos secundarios que actúan como

atrayente o repelente de individuos de la clase insecta, principalmente

de los órdenes Diptera, Coleoptera y Hemiptera. Por lo tanto, T. erecta contiene Piretrinas y Tiofenos, que son los metabolitos responsables con propiedades alelopaticas contra insectos y gusanos 7. Sin embargo, las propiedades volátiles de O. basilicum no producen repelencia para algunos insectos, de igual forma otros autores 8,

encontraron que al aplicar extractos de albaca, ají, salvia y anamú

determinaron una mayor incidencia de insectos, mostrando daño en frutos

de banano; por lo que los productos no fueron eficientes para el control

de Colaspis sp., concluyendo que la aromática O. basilicum

es fuente de alimento y hospedero para una amplia diversidad de

insectos. En estudios similares se encontró la presencia de 18 familias y

22 especies asociadas a O vulgare, algunas alimentándose de

tallos y hojas y otros sobre la planta sin definir la relación con la

misma. Los Tetraniquidos o arañas rojas (Tetranychidae) fueron los más

abundantes, seguido por dos especies de hormigas (Formicidae) y de una

especie de chapulín (Orthoptera), así como la chinche Fulvios sp (Miridae), que se alimenta de larvas de coleópteros 9.

La

población de insectos asociados a la inflorescencia del rambután se

distribuyó en tres grupos: fitófagos, enemigos naturales y

polinizadores. Dentro de los fitófagos se observó con mayor abundancia y

frecuencia a la familia Formicidae y con menor frecuencia a las

familias Cicadadellidae, Membracidae, Cercopidae, Otitidae,

Droshophilidae, Brentidae, Staphylinidae. Dentro los enemigos naturales

colectados destacan la familia Therevidae, Sphecidae, Culicidae,

Termitidae, Reduviidae y Chysopidae 10.

Los polinizadores en orden de importancia fueron: Apidae y Vespidae. Sin

embargo, en el agroecosistema rambután - plantas aromáticas, los

fitófagos con mayor abundancia fueron la familia Formicidae, los cuales

se encontraron sobre las plantas aromáticas causando defoliación.

Insectos de hábitos parasitoides y depredadores destacan las familias

Sirphydae, Culicidae, Vespidae, Braconidae, Pteromalidae, Tachinidae y

Muscidae. Los polinizadores en orden de importancia fueron: Apidae y

Syrphidae. Algunos autores reportan que la familia Vespidae puede ser un

insecto polinizador y otros como depredador 11.

Del total de insectos colectados (13 481), los agrupados según su

actividad asociados al agroecosistema rambután representan el 10,37 %,

el resto (89,63 %) no se ha reportado con alguna actividad específica

para el cultivo.

Las cochinillas o piojos harinosos (Planococcus lilacinus)

son insectos de la familia Pseudococcidae, pertenecientes al Orden

Hemiptera, limitando la comercialización de diversos cultivos y

frutales. Es una plaga cosmopolita, en México se considera de

importancia cuarentenaria 12. Durante el

desarrollo de esta investigación, esta plaga se presentó en la etapa de

desarrollo y madurez del fruto de rambután; sin embargo, el porcentaje

de infestación (Tabla 1), fue mayor en O. vulgare (0,77 %) y O. basilicum (0,31 %), siendo menor la presencia en T. erecta (0,25 %) y el testigo (0,15 %). Por lo tanto, O. vulgare y O. basilicum se comportaron como plantas atrayentes del piojo harinoso (Tabla 1). Otras especies como menta americana (Lippia alba Mill), salvia (Lippia geminata Kunth) y albahaca morada (Ocimum sanctum L.), son hospederas de piojo harinoso, por lo que las familias más apetecidas son las malváceas, leguminosas y moráceas 13.

El ciclo reproductivo del rambután para la

costa del Soconusco, Chiapas, fluctúa de 100 a 130 días, el periodo de

floración está comprendido entre los meses de enero - abril y el periodo

de cosecha junio - julio. Asimismo, para otros países como Honduras y

Costa Rica el ciclo de esta exótica fruta varia de 105 a 130 días. La

producción temprana (mayo) de frutas de rambután adquieren altos

precios, provocando que la calidad de la fruta se deterioré por las

cosechas de frutos inmaduros (verdes). Con base a los resultados de la

investigación, la floración del rambután en las asociaciones con O. vulgare, O. basilicum y el testigo dio inicio en la primera quincena del mes de febrero y T. erecta

a finales del mes de enero, teniendo así la cosecha durante los meses

mayo - junio. Siendo el testigo con el mayor número de días desde

floración (DDF) hasta la madurez comercial de los frutos con 127 DDF,

siguiendo T. erecta con 121 DDF, posteriormente O. vulgare a los 120 DDF y O. basilicum

con 110 DDF reduciendo el número de días para la cosecha de rambután en

Chiapas, bajo las condiciones edafoclimáticas presentes en el área de

investigación. De acuerdo a algunos investigadores 14,

uno de los responsables de este suceso es el ácido salicílico,

metabolitos secundarios mejor estudiados en cuanto a su distribución

natural y función, este fenol simple está presente en las estructuras

reproductivas y en las hojas de especies aromáticas empleadas en la

agricultura como las que se usaron para este trabajo. Éste ácido induce

la floración, participa en la regulación del potencial de las membranas

celulares y la resistencia de enfermedades 15.

Existen reportes que mencionan el efecto del ácido salicílico en la

inducción de la floración del crisantemo, 37 días después de trasplante

(ddt) en comparación con el testigo en donde ocurrió a los 43 ddt.

Asimismo, el ácido salicílico reduce la síntesis de etileno y en algunas

especies esto origina un retardo de la senescencia de flores o

inducción de la floración 16, como es el caso de O. basilicum que se cosechó con 17 días de diferencia en comparación con el testigo. Según otros autores 17,

el cultivo de rambután se cultiva en zonas que van desde los 0 hasta

los 800 m s.n.m.; rango de altitudes, donde las especies aromáticas

ofrecen una importante alternativa para la precocidad de la cosecha, ya

que la producción de fruta fresca temprana adquiere un valor de USD$

1,10 por kg, mientras que 15 días después, el precio se fija a USD$

0,55.

El rambután es una fruta no climatérica,

razón por la cual la fruta debe cosecharse cuando ha alcanzado las

óptimas condiciones de calidad comestible y apariencia visual. La

comercialización de frutos de rambután se basa en las normas de calidad

(CODEX STAN 246-2005) 18. De acuerdo a los

resultados obtenidos en la asociación de plantas aromáticas en contorno

al área de goteo de árboles de rambután, se observó que T. erecta tiene una marcada influencia sobre la calidad comercial de frutos (Tabla 2),

sin embargo, no se alcanza la calidad en el peso de frutos para la

comercialización internacional. Aun cuando la calidad de los frutos se

encuentre dentro de los rangos comprendidos en las normas de

exportación, se deben considerar otras prácticas agronómicas como: la

poda, anillado, estrés hídrico y sus combinaciones, que en conjunto

determinan la vida del así como la calidad de lo0s frutos y su

poscosecha 19. Así mismo, un estudio sobre

polinización entomófila y raleo de frutos en rambután, mencionan que la

libre polinización del rambután influye en el peso del fruto (25 g),

seguido por el tratamiento raleo de frutos con 18,2 g, comparado con los

tratamientos donde se controló la visita de insectos en las

inflorescencias del rambután 20. De la

misma forma, el amarre de frutos fue mayor con la libre polinización

(7,35 %) comparado con el tratamiento con flores cubiertas (2,85 %).

CONCLUSIONES

Las asociaciones con O. basilicum y O. vulgare

en el cultivo de rambután favorecen la atracción de insectos,

aumentando la abundancia entomológica en el cultivo; asimismo, responden

positivamente a la infestación del piojo harinoso

(Planococcuslilacinus) hemíptero de la clase insecta. Son excelentes

plantas para la atracción de formícidos, insectos considerados como

fitófagos asociados a la inflorescencia del rambután; sin embargo, O. basilicum, fue la mejor asociación en la atracción de insectos benéficos; parasitoides (0,92 %) y depredadores (0,24 %).

T. erecta fue la mejor asociación que actúa como repelente de insectos.

La calidad comercial del fruto se ve favorecida por la asociación de aromáticas, especialmente con T. erecta.

Traducir DocumentoOriginal ArticlePotential effect of aromatic plants on insect population and fruit quality in rambutan (Nephelium lappaceum L)

Francisco Javier Marroquín-Agreda [1]

Magdiel Gabriel-Hernández [1]

Humberto Osorio-Espinoza [1] [*]

Ernesto Toledo-Toledo [1]

[1] Universidad

Autónoma de Chiapas. Entronque Carretera Costera y Estación Huehuetán;

Apdo. Postal 34; Huehuetán, Chiapas, México. CP 30660

[*] Author for correspondence. hosorio2503@yahoo.com

ABSTRACTRambutan acreage in

the Soconusco, region of Mexico, Chiapas is over 2000 hectares, mostly

under monocultural agrosystems based on the high use of external inputs.

The experiment was carried out from august 2013 to june 2014 in a four

year-old plantation (from planting), located in the Huixtla

municipality, Chiapas; with the objective of evaluating the allelopathic

and attractive potential of aromatic plants on the entomofauna and

commercial quality of rambutan, three plant species were evaluated: Origanum vulgare, Ocimum basilicum and Tagetes erecta,

associated with the cultivation of rambutan; under an experimental

design in random blocks with four treatments and five repetitions where

indicators of abundance, food habit of insects and quality of fruits of

rambutan were measured. The results showed that the aromatic plants

increase the abundance of insects, with a total of 13 481 individuals

distributed in 13 orders and 87 families; 32.00 % corresponds to insects

associated with Ocimum basilicum, 30.03 % Origanum vulgare, 21.07 % to the control and 16.88 % to Tagetes erecta. Ocimum basilicum had the highest percentage of beneficial insects (2.08 %), O. vulgare (1.15), T. erecta

(1.11), the control being lower (0.85 %); however, O vulgare presented

the highest number of mealy bugs. In the reproductive phase there are

differences in the dates of flowering and anthesis; where, O. basilicum

has a precocity of 17 days with respect to the traditional system. The

parameters of commercial quality (weight and soluble solids) are

improved with the association of aromatic plants, mainly with Tagetes erecta.

INTRODUCTIONThe rambutan (Nephelium lappaceum L.) in Mexico is cultivated in five states: Chiapas, Oaxaca, Tabasco, Michoacán and Nayarit 1. The Soconusco, Chiapas, emphasizes to overcome the 2000 ha 2,

surface that is distributed in 716 producers of this exotic fruit;

being thus the backyard horticultural system and the economic pillar of

numerous family nuclei. However, production methods and techniques are

based on decisions of chemical control and under a monoculture

structure; which favors the deterioration of the productivity and

quality of the fruit, in addition to the incidence of insects, such as

the case of the mealybug (Planococcus lilacinus) hemiptera of the

insect class, considered a pest; however, the United States of North

America has this pest in quarantine, thereby affecting the export of

fruits to countries such as Japan 3.

In the face of agroproductive deterioration, the incidence of pests in fruit orchards and the promising results of Tagetes erecta on the growth and quality of Cedrela odorata; the association of aromatic species such as oregano (Origanum vulgare), basil (Ocinum basilicum) and dead flower (Tagetes erecta)

could offer a potential in allelopathy of pests and attractants of

pollinating insects, or as plant breeders in quality or floral inductor

of fruit species 4. Given this premise, the

present work focuses its objectives on the evaluation of the

allelopathic and attractive potential of aromatic plants on the

entomofauna and commercial quality of rambutan.

MATERIALS AND METHODSThe

investigation was carried out during the productive period August 2013 -

June 2014, in a plot cultivated with rambutan of four years of

established, with distancing of 10x10 m. Located in Huixtla

municipality, Chiapas, Mexico, in the parallels 15° 10'23.00'' north

latitude and 92° 32'02.00'' west longitude, at an altitude of 27 m

a.s.l. The environmental conditions prevail with average annual

temperature of 28 °C, minimum of 14 °C and maximum of 42 °C. Rainfall

ranges between 2.500 and 3.000 mm per year. The predominant soils are of

the cambisol type, with a light loam-silty texture. During the

experiment the individual interactions of three species of aromatic

plants (Origanum vulgare, Ocimum basilicum and Tagetes erecta)

associated with a system of rambutan production were evaluated, all of

them in comparison with the control (without association). The spatial

arrangement of the aromatic species was in contour grooves to the outer

limit of the drip area of the rambutan trees, with a distance of 40 cm

between rows and 30 cm between plants. When the aromatic species reached

a height ±50 cm vegetative pruning was carried out with frequency of 15

days, strategy for the liberation of secondary metabolites and to

promote the production of biomass. The treatments were randomized under

an experimental design of randomized complete blocks, with four

treatments (three associations+control) and five repetitions (rambutan

tree), in a total area of 4 200 m2.

For

the capture of the insects, an entomological net of 50 cm diameter was

used, 10 double hits of the net were made, five on the aromatic plants

and five on the rambutan trees, during the period November 2013 - June

2014 (flowering of rambutan). The classification was carried out in the

biology laboratory of the Faculty of Agricultural Sciences of the

Autonomous University of Chiapas, with the support of a binocular

digital stereoscope model ED-1805 and taxonomic keys 5,

based on a guide of beneficial insects. , was classified according to

order and family, as well as their eating habits (predators, parasitoids

and pollinators) 6. Also, during the

development of the fruits of rambutan, abundance evaluations of the

mealybug were carried out and in the visual physiological maturity of

the fruits, 25 fruits were collected from the trees for treatment, to

which the quality parameters were determined: fruit weight (g), fruit

diameter (cm), fruit length (cm), aryl weight (g), aryl diameter (cm),

aryl length (cm), soluble solids (°Brix), pH and titratable acidity.

The

results were analyzed with the statistical software Statgraphics

centurion version XVI.I, with which a variance analysis of simple

classification and application of the Tukey multiple range test was

performed for the cases of significance at a 95 % probability of error.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONAbundance

of insects refers to the wealth of individuals that present themselves

in a defined spatio-temporal dimension, resulting from the set of

interactions between species that are integrated. The total insect

abundance accumulated during the development of the experiment was 13

481 individuals in an area of 4 200 m2; according to the statistical analysis and the Tukey test. The associations with the highest total abundance were O. basilicum with 4 315 individuals, representing 32 % of the total of insects collected; O. vulgare with 4.049 (30 %) and control 2 841 (21 %), compared with T. erecta 2 276 (17 %); the latter was statistically lower than O. basilicum (Figure 1).

* Different letters show statistical difference according to Tukey at 95 % reliability

Abundance of insects in a rambutan orchard with interspersed aromatic species

The fluctuations of the abundance of insects

associated with aromatic plants, is based on being a source of nectar,

pollen, biomass and secondary metabolites that act as attractant or

repellent of individuals of the insect class, mainly of the orders

Diptera, Coleoptera and Hemiptera. Therefore, T. erecta contains

Pyrethrins and Thiophenes, which are the responsible metabolites with

allelopathic properties against insects and worms 7. However, the volatile properties of O. basilicum do not produce repellency for some insects, likewise other authors 8,

they found that when applying extracts of basil, pepper, sage and

guinea henweed they determined a higher incidence of insects, showing

damage in banana fruits; so the products were not efficient for the

control of Colaspis sp., concluding that the aromatic O. basilicumes

source of food and host for a wide diversity of insects. Similar

studies found the presence of 18 families and 22 species associated with

O vulgare, some feeding on stems and leaves and others on the

plant without defining the relationship with it. Tetraniquids or red

spiders (Tetranychidae) were the most abundant, followed by two species

of ants (Formicidae) and one species of grasshopper (Orthoptera), as

well as the bug Fulvios sp (Miridae), which feeds on coleopteran larvae 9.

The

population of insects associated with the inflorescence of rambutan was

divided into three groups: phytophages, natural enemies and

pollinators. Among the phytophages, the Formicidae family was more

abundantly and frequently observed, and less frequently, the families

Cicadadellidae, Membracidae, Cercopidae, Otitidae, Droshophilidae,

Brentidae, Staphylinidae. Among the natural enemies collected are the

family Therevidae, Sphecidae, Culicidae, Termitidae, Reduviidae and

Chysopidae 10. The pollinators in order of

importance were: Apidae and Vespidae. However, in the agroecosystem

rambutan-aromatic plants, the phytophages with the greatest abundance

were the Formicidae family, which were found on the aromatic plants

causing defoliation. Insects of parasitoid habits and predators include

the families Sirphydae, Culicidae, Vespidae, Braconidae, Pteromalidae,

Tachinidae and Muscidae. The pollinators in order of importance were:

Apidae and Syrphidae. Some authors report that the Vespidae family can

be a pollinating insect and others as a predator (11.

From the total of insects collected (13 481), the grouped ones

according to their activity associated with the agroecosystem rambutan

represent 10.37 %, the rest (89.63%) has not been reported with any

specific activity for the crop.

The mealybugs (Planococcus lilacinus)

are insects of the family Pseudococcidae, belongs to Hemiptera order,

limiting the commercialization of diverse crops and fruits. It is a

cosmopolitan pests and in Mexico it is considered of cuarentenary

importance 12. During the development of

this research, this pest was presented in the stages of development and

maturity of rambutan fruits, however, the percentage of infesting (Table 1), was higher in O. vulgare (0.77 %) and O. basilicum (0.31 %), being samller in presence of T. erecta (0.25 %) and the control (0.15 %). Furthermore, O. vulgare and O. basilicum behave as attracting plants of mealybugs (Table 1). Other species like spearmint (Lippia alba Mill), salvia (Lippia geminata Kunth) and basil (Ocimum sanctum L.), are hosted of mealybugs, for this, the families more delicious for it are son las malváceas, leguminous y moráceas 13.

The reproductive cycle of rambutan for the

coast of Soconusco, Chiapas fluctuates from 100 to 130 days, the

flowering period is comprised between the months of January - April and

the harvest period June - July. Likewise, for other countries such as

Honduras and Costa Rica, the cycle of this exotic fruit varies from 105

to 130 days. The early production (May) of rambutan fruits acquire high

prices, causing the quality of the fruit to deteriorate due to the

immature (green) fruit harvests. Based on the results of the research,

the flowering of rambutan in the associations with O. vulgare, O. basilicum and the witness started in the first half of February and T. erecta

at the end of January, thus having the harvest during the months

May-June. Being the witness with the largest number of days from

flowering (DFF) until the commercial maturity of the fruits with 127

DFF, following T. erecta with 121 DFF, later O. vulgare at 120 DFF and O. basilicum

with 110 DFF reducing the number of days for the harvest of rambutan in

Chiapas, under the edaphoclimatic conditions present in the research

area. According to some researchers 14,

one of the responsible for this event is salicylic acid, secondary

metabolites best studied in terms of its natural distribution and

function, this simple phenol is present in the reproductive structures

and leaves of aromatic species employed in agriculture like those used

for this work. This acid induces flowering, participates in the

regulation of cell membrane potential and the resistance of diseases 15.

There are reports that mention the effect of salicylic acid in the

induction of flowering of the chrysanthemum, 37 days after

transplantation (DAT) compared to the control where it occurred at 43

DAT. Likewise, salicylic acid reduces the synthesis of ethylene and in

some species this causes a delay in the senescence of flowers or

induction of flowering 16, as is the case of O. basilicum that was harvested 17 days apart in comparison with the control. According to other authors 17,

the cultivation of rambutan is cultivated in zones ranging from 0 to

800 m a.s.l.; altitude range, where the aromatic species offer an

important alternative for the precocity of the harvest, since the

production of early fresh fruit acquires a value of USD $ 1.10 per kg,

while 15 days later, the price is set at USD $ 0.55.

The

rambutan is a non-climacteric fruit, which is why the fruit must be

harvested when it has reached the optimum conditions of edible quality

and visual appearance. The commercialization of rambutan fruits, it is

based on the quality standards (CODEX STAN 246-2005) 18.

According to the results obtained in the association of aromatic plants

in contour to the area of trickling of rambutan trees, it was observed

that T. erecta has a marked influence on the commercial quality of fruits (Table 2),

Even when , the quality in fruits are established ranges in export

standards, another agronomic practice should be considered such as:

pruning, banding, water stress and their combinations, that permits

shelf life, fruits quality and the post-harvest 19.

Likewise, a study on entomophilous pollination and thinning of fruits

in rambutan, mention that the free pollination of rambutan influences

the fruit weight (25 g), followed by the treatment of fruit thinning

with 18.2 g, compared with treatments where the visit of insects in the

inflorescences of rambutan was controlled 20.

In the same way, the mooring of fruits was greater with the free

pollination (7.35 %) compared with the treatment with covered flowers

(2.85 %).

CONCLUSIONS

The associations with O. basilicum and O. vulgare

in the cultivation of rambutan favor the attraction of insects, thus

increasing the entomological abundance in the crop; likewise, they

respond positively to the infestation of the mealybug

(Planococcuslilacinus) hemiptera of the insect class. They are excellent

plants for the attraction of formicids, insects considered as

phytophagous associated to the inflorescence of the rambutan; however, O. basilicum, was the best association in the attraction of beneficial insects; parasitoids (0.92 %) and predators (0.24 %).

T. erecta was the best association that acts as an insect repellent.

The commercial quality of the fruit is favored by the association of aromatics, especially with T. erecta.