La palma de cocotero (Cocos nucifera L.) es un cultivo tropical perenne de gran utilidad, que crece en alrededor de 80 países. En Cuba, el cultivo ocupa aproximadamente 13 186 ha, con un rendimiento promedio de 4,5 t ha-1 (1, siendo de gran importancia la producción de posturas que garanticen el material necesario para la renovación y el fomento de nuevas áreas. Un estudio diagnóstico llevado a cabo en el Centro de Desarrollo de la Montaña de la provincia Guantánamo mostró que en los viveros se obtienen bajos índices de germinación, así como posturas poco vigorosas que provocan alta mortalidad de las mismas, al ser trasladadas al campo. Esto pudiera estar asociado a diferentes factores como el empleo de semillas con embriones inmaduros, unido a factores limitantes de los suelos como aireación, retención de humedad y baja fertilidad 2.

El empleo de un sistema de abonado orgánico que tenga en cuenta el uso del humus de lombriz, combinado con biofertilizantes permitiría asegurar condiciones favorables para la germinación y posterior crecimiento de las plantas 3. Se conoce que la adición del humus de lombriz a los suelos y a los sustratos, incrementa considerablemente el crecimiento y la productividad de una gran cantidad de cultivos, mediante la mejora significativa en las propiedades físicas, químicas y biológicas de los mismos 4.

Las rizobacterias promotoras del crecimiento vegetal (RPCV) constituyen uno de los biofertilizantes de amplio uso por los mecanismos directos e indirectos de promoción del crecimiento 5,6; siendo, Azotobacter chroococcum uno de los géneros bacterianos fijadores de nitrógeno, más empleados 7,8. El empleo de esta especie permite el acortamiento del período de permanencia de las plantas en los semilleros y favorece el incremento en los parámetros morfológicos de las plantas 9, lo que las convierte en una alternativa a evaluar en el crecimiento de las posturas de cocotero. En Cuba, desde 1990, se desarrolla un programa de producción y aplicación de A. chroococcum con cepas seleccionadas, dentro de las cuales se destaca la cepa INIFAT-8 10. La presente investigación se desarrolló con el objetivo de determinar la influencia de un sistema de abonado orgánico e inoculación de A. chroococcum sobre la germinación de semillas y el crecimiento de las posturas de cocotero en un vivero convencional.

El experimento se desarrolló en los viveros “Playa Duaba” y “Cabacú”, ubicados en el municipio Baracoa, provincia Guantánamo, sobre los suelos Arenosol háplico (ARh) y Gleysol Flúvico háplico (GFLh), respectivamente 11. El experimento se repitió durante dos años consecutivos, en el cual se estudiaron las combinaciones de tres niveles del sustrato Suelo: Humus de lombriz: Fibra de Coco (S:HL:FC) (10:1:1, 4:1:1, 2:1:1, v/v/v) 12 con tres cepas de A. chroococcum (CDM-1, CDM-2 e INIFAT-8).

Las cepas de A. chroococcum, procedieron de la colección del Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Fundamentales de Agricultura Tropical “Alejandro de Humboldt” (INIFAT). Las cepas CDM-1 y CDM-2, fueron aisladas de los suelos presentes en los viveros “Playa Duaba” y “Cabacú”, respectivamente. Los bioproductos confeccionados poseían una concentración de 9 x 1010 UFC por g de soporte 13) y se aplicaron por aspersión directa al suelo y la semilla a una dosis de 1 kg ha-1 (14.

Se utilizaron, adicionalmente, tres controles constituidos por fertilización mineral (NPK 100 %) para lo que se empleó la fórmula completa 9:13:17 a razón de 45 g por semilla fraccionado al 33 % a los 30 días posteriores a la siembra (dps) y el resto a los 90 dps 15, el sustrato S:H:FC 1:1:1 v/v/v y el suelo. En todos los casos para la elaboración del sustrato se utilizó el suelo presente en el vivero.

Las semillas fueron obtenidas de plantas madres sanas, pertenecientes al ecotipo domesticado de cocotero “Indio Verde-1” 16. Se empleó un diseño en bloques al azar con arreglo bifactorial (3x3) y tres réplicas. Cada parcela experimental dentro del bloque contenía 20 semillas, sembradas a una distancia de 0,05 x 0,20 m.

El experimento tuvo una duración de 180 días. A los 120 dps se calculó el índice de velocidad de germinación (IVG) mediante la fórmula 17, donde n es el número de semillas germinadas y el intervalo de tiempo en que germinaron las semillas. Se evaluaron las semillas germinadas en los tiempos 30, 60, 90 y 120 días. A los 180 dps se muestrearon 15 plantas por réplica y se evaluó la altura del vástago (cm) y el diámetro en la base del vástago (cm) 18. Se realizó, además, el conteo de poblaciones de A. chroococcum en la rizosfera 19.

Los datos de la variable conteo de poblaciones de A. chroococcum en la rizosfera se transformaron por la fórmula log(x). Los resultados para todas las variables evaluadas mostraron un comportamiento similar en los dos años estudiados, por lo que se analizaron los datos correspondientes a la media de los dos años. Para el procesamiento estadístico de los tratamientos se utilizó el Análisis de Varianza factorial y la Prueba de Rangos Múltiples de Duncan (p(0,05). Para comparar los controles con cada uno de los tratamientos se realizó un ANOVA de clasificación doble, se determinó el EE, con el cual se calculó el intervalo de confianza (IC) para los controles con un nivel de significación del 95 % y se verificó si las medias de cada tratamiento estaban contenidas dentro del intervalo de confianza. Se empleó el paquete estadístico STATGRAPHIC versión 15.2.

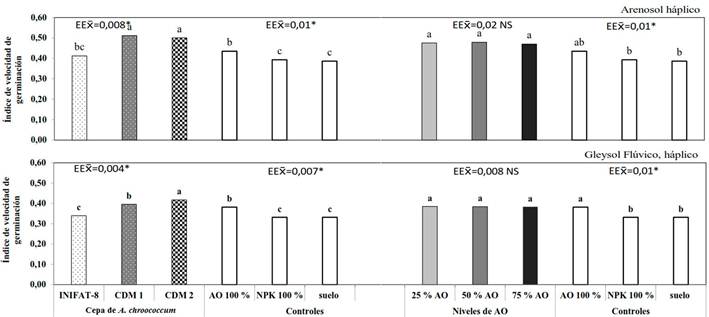

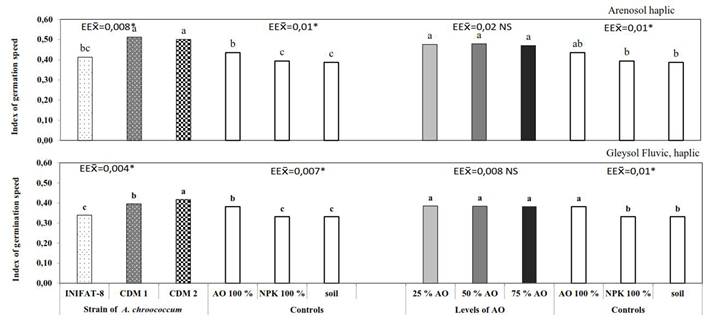

El análisis realizado mostró interacción de los factores en los dos suelos en estudio, para todas las variables evaluadas, excepto para el IVG. No se encontró efecto de los niveles de abono orgánico sobre el IVG, no siendo así para el factor cepas de A. chroococcum, el cual sí tuvo significación.

Se observó que en el suelo ARh las cepas aisladas de los suelos estudiados (CDM-1 y CDM-2) no mostraron diferencias entre sí y fueron superiores a la cepa INIFAT-8 y a los controles, con valores promedios entre 0,50 y 0,52, mientras que en el suelo GFLh los mejores valores correspondieron a la cepa CDM-2, con un valor de 0,42 (Figura 1). En los tratamientos inoculados con ambas cepas no se observó diferencias significativas entre los tres niveles de los abonos orgánicos y el control S:HL:FC (1:1:1).

Con respecto al control S:HL:FC (1:1:1), en el suelo ARh ,el tratamiento donde se empleó la cepa CDM-1 con S:H:FC (4:1:1), mostró una reducción en cuatro días el inicio de la germinación, mientras en el suelo GFL, disminuyó en 12,8 días (datos no mostrados).

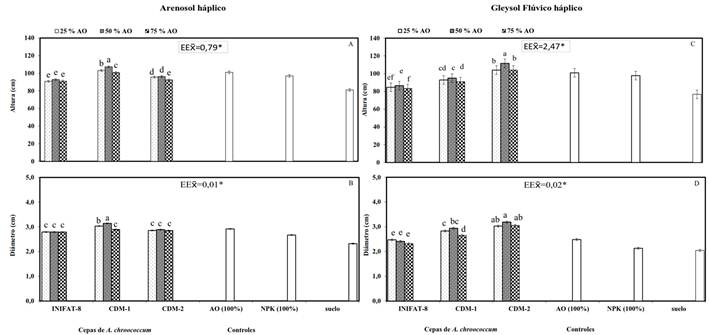

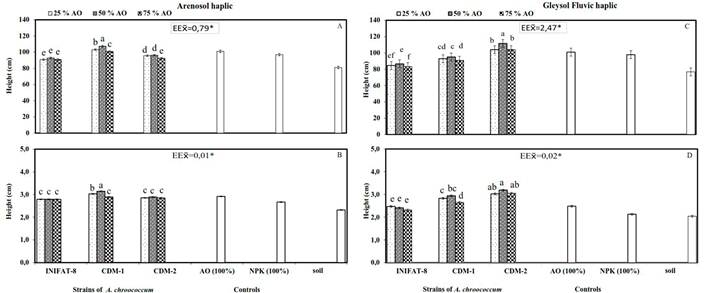

En la variable altura del vástago, el mejor comportamiento en el suelo ARh se observó, cuando se empleó la cepa CDM-1 con S:HL:FC (4:1:1), la cual difirió de los restantes tratamientos y de los controles de referencia (Figura 2A). De forma general, las variantes donde se inocularon las cepas de A. chroococcum combinadas con los tres niveles de los abonos orgánicos, resultaron superiores cuando fueron comparadas con el control suelo.

Al analizar los resultados en el suelo GFLh se encontró, que al combinarse A. chroococcum con los tres niveles de abono orgánico, la cepa CDM-2 influyó en la obtención de los mejores valores para la altura en la base del vástago (Figura 2C), seguida por CDM-1 y por INIFAT-8, con la cual se obtuvieron los valores más bajos. La cepa CDM-2, combinada con S:HL:FC (4:1:1), favoreció la mejor respuesta para esta variable, con diferencia del resto de los tratamientos y de los controles.

El análisis del diámetro en la base del vástago en el suelo ARh, mostró los mejores resultados al combinarse la cepa CDM-1 y S:HL:FC (4:1:1), con diferencia de los restantes tratamientos y los controles. Por otra parte, los tratamientos donde se empleó CDM-2 con los tres niveles de abono orgánico, mostraron similitud al compararse con los tratamientos inoculados con la cepa INIFAT-8. Se obtuvo, además, que estas últimas variantes mencionadas mostraron similitud con el control S:HL:FC (1:1:1) y diferencias con los controles NPK 100 % y el suelo (Figura 2B).

Para los tratamientos realizados con el suelo GFLh (Figura 2D) los mejores resultados se obtuvieron, con la combinación de la cepa CDM-2 y los tres niveles de abono orgánico, los que mostraron diferencias con los controles.

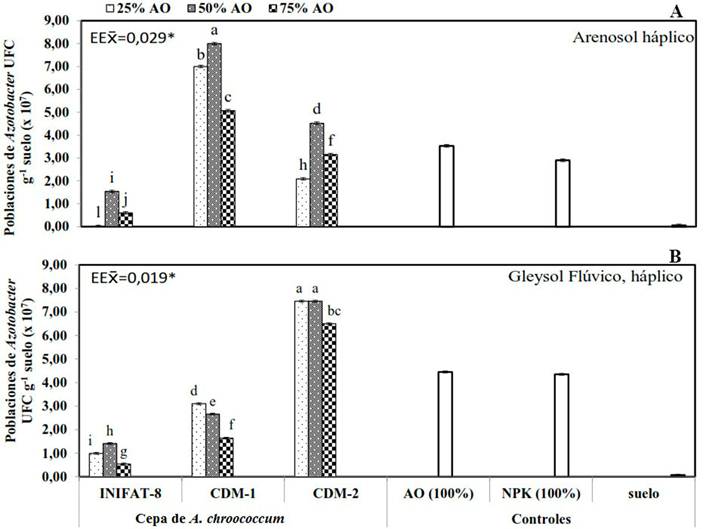

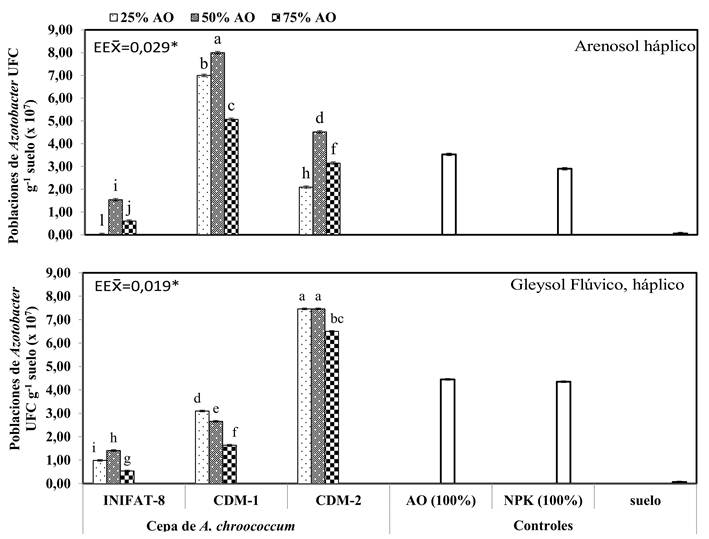

En el análisis de la cuantificación de las poblaciones de Azotobacter en el suelo ARh (Figura 3A), los mejores resultados se encontraron en el tratamiento donde se combinó la cepa A. chroococcum CDM-1 y S:HL:FC (4:1:1) con diferencias significativas, respecto a los restantes tratamientos y los controles. Por otro lado, en las variantes donde se utilizó el suelo GFLh en la preparación del sustrato, el conteo de las poblaciones de Azotobacter en la rizosfera (Figura 3B), mostró las mejores respuestas con la inoculación de la cepa A. chroococcum CDM-2, combinada con los niveles de S:HL:FC 10:1:1 y 4:1:1, con diferencias significativas del resto de los tratamientos y los controles. En ambos suelos los más bajos niveles se alcanzaron con la cepa INIFAT-8 y el control suelo.

La falta de respuesta en el tratamiento conformado por el suelo sin aplicación de Azotobacter, posiblemente esté relacionada con los factores limitantes de estos suelos, así como con las bajas poblaciones de Azotobacter presentes en los mismos.

Los bajos porcentajes de retención de humedad en el suelo Arenosol háplico pudo dificultar el flujo de masas y la difusión de nutrientes, limitando la absorción de nutrimentos por la planta 20. Por otro lado, la disminución de los niveles de oxígeno en el suelo GLFh debido a sus propiedades gléyicas 11, pudo haber impedido el normal desarrollo de las raíces, y con ello, una baja absorción de agua y nutrimentos. Estas propiedades pudieron haber sido mejoradas con el empleo del abonado orgánico, ya que el mismo permite la formación de agregados del suelo, los cuales mejoran el balance entre macros y microporos y, con ello, la retención de agua, además del incremento de los niveles materia orgánica y el estado de fertilidad del suelo 21.

Los estudios presentados proporcionan evidencia de que las cepas de Azotobacter empleadas respondieron con más efectividad en los suelos de los cuales fueron aisladas. Se encontró la mejor respuesta con el empleo de S:HL:FC (4:1:1) al combinarse con la cepa CDM-1 en el ARh y con la cepa CDM-2 en el GFLh, lo que posibilita disminuir los niveles de abonado orgánico empleados en un 50 %, mediante el empleo de esta rizobacteria.

Se ha encontrado que a las concentraciones de estas bacterias presentes en los suelos cubanos (104-105 UFC g-1 de suelo rizosférico), es difícil observar respuestas en el crecimiento de las plantas, por lo que la inoculación de las mismas permite incrementar los niveles existentes (hasta 109 UFC g-1 de suelo rizosférico) favoreciendo una respuesta positiva de los cultivos 13.

Las cepas autóctonas, al estar mejor adaptadas a las condiciones estudiadas, fueron capaces de funcionar con mayor rapidez y efectividad que la cepa INIFAT-8, la que al parecer, pudo encontrar en estos suelos antagonismo con las poblaciones microbianas residentes. Se plantea que cuando se inoculan bacterias de vida libre, la variabilidad en las respuestas encontradas está sujeta a diferentes condiciones, entre las que se encuentran, la presencia de las comunidades microbianas residentes de la rizosfera, con las que se establecen interrelaciones de sinergismo y antagonismo 22.

La respuesta observada para los diferentes niveles de abonado orgánico estuvo dada por el hecho de que al ser Azotobacter una bacteria heterótrofa, utiliza varias fuentes orgánicas de energía, que incluyen hemicelulosa, almidón, azúcares, alcoholes y ácidos orgánicos, que provienen de la materia orgánica presente en los suelos 23, sin embargo, las actividades de este grupo bacteriano, en su relación con la planta, se verán favorecidas por los bajos niveles de nitrógeno en el suelo, a los cuales les favorece la fijación de este elemento. Por otra parte, su efectividad disminuye en la medida que los suelos tienen mayor contenido de materia orgánica. Cuando se aplica biofertilizante se debe fertilizar con enmiendas orgánicas, para evitar el empobrecimiento del suelo 15.

Los resultados positivos observados en la estimulación de la germinación de las semillas y en el crecimiento de las posturas de cocotero, pudieran estar asociados a la forma de aplicación del inóculo de este biofertilizante. El mismo se aplicó por aspersión directa a la semilla en el momento de la siembra, lo que pudo favorecer la hidratación del mesocarpo y endocarpo y, de esta forma, lograr que se alcanzara con mayor rapidez la humedad óptima para que el embrión iniciara la germinación.

Este efecto, unido a la capacidad que tienen estas bacterias de producir sustancias reguladoras del crecimiento 24,25, propició que las mismas, al penetrar la corteza seminal, aceleraran la germinación y el desarrollo radicular. En el genoma de algunas cepas de rizobacterias aisladas de la rizosfera del cocotero, ha sido identificado el gen H2S, el cual está involucrado en la síntesis de sulfito de hidrógeno, compuesto vinculado con el incremento de la germinación de semillas 26.

Otro de los mecanismos propuestos, mediante el cual el Azotobacter pudo haber promovido el crecimiento vegetal, es la producción de la enzima ácido 1-amino-ciclopropano1-carboxilato desaminasa (ACC desaminasa), la cual, además de prevenir la ocurrencia de enfermedades 27, puede facilitar el crecimiento vegetal y favorecer el inicio del crecimiento del embrión, unido a la síntesis de ácido indol acético (AIA) y la regulación de los niveles de etileno 24.

Diferentes autores sugieren la importancia del etileno en el proceso de germinación 26,28-30, en la disminución de la dormancia y la emisión de la radícula en diferentes especies 28-30. La producción de etileno comienza inmediatamente después de la imbibición y se incrementa con el tiempo durante la germinación 22.

En cepas de rizobacterias aisladas del cultivo del coco, se ha demostrado que la producción de AIA, ácido giberélico, amonio, sideróforos, proteasas, catalasas, celulasas, la solubilización de los fosfatos 29, la fijación de N231 así como la protección ante diferentes estrés bióticos 32-35 y abióticos 36,37 son los mecanismos mediante los cuales estas bacterias promueven el crecimiento vegetal, lo que las sitúa como potenciales para la producción de bioinoculantes en el manejo orgánico de este cultivo 26,30.

Se demostró que es posible disminuir los niveles de abonado orgánico empleados en un 50 %, mediante la inoculación de cepas de Azotobacter chroococcum aisladas de los suelos en estudio.

La combinación Suelo:Humus de lombriz:Fibra de Coco (S:HL:FC) (4:1:1) con A. chroococcum CDM-1 en el suelo ARh y A. chroococcum CDM-2 en el suelo GFLh, favorecieron el incremento de las variables estudiadas, las que alcanzaron niveles superiores a los obtenidos con la dosis recomendada de fertilización mineral y el abonado orgánico.