Translate PaperArtículo originalControl del rajado de los frutos en plantas de mandarino Clementino

[0000-0003-3508-7794] Marco Daniel Chabbal [1] [*]

[0000-0002-0484-9736] Maria de las Mercedes Yfran-Elvira [1]

[0000-0002-9139-4759] Laura Itatí Giménez [1]

[0000-0003-2526-4881] Gloria Cristina Martínez [1]

[0000-0001-6807-8902] Lidia Agostina Llarens-Beyer [1]

[0000-0003-1559-3112] Víctor Antonio Rodríguez [1]

[*] Autor para correspondencia: marc.chabbal@gmail.com

RESUMENUno de los

defectos físicos más extendidos que limitan la producción citrícola es

el rajado de la corteza de los frutos y los frutos partidos

desprendidos. El objetivo de este trabajo fue evaluar dosis de nitrato

de calcio y carbonato de calcio y magnesio para el control del rajado de

la fruta, la producción y calidad de mandarina ʹClementinaʹ. Los

tratamientos, T1: control, T2: 225 g Ca(NO3)2, T3: 450 g Ca(NO3)2, T4: 720 g Ca(NO3)2 y T5: 720 g de CaMg(CO3)2 Planta-1

fueron aplicados durante tres campañas consecutivas en marzo (50 %) y

en septiembre (50 %), meses que coinciden con el crecimiento y

desarrollo de frutos y la brotación de primavera y floración

respectivamente. El diseño experimental fue en bloques completos al

azar, con cuatro réplicas y dos plantas por réplica. Se tomaron muestras

foliares en marzo, para cada tratamiento en las tres campañas,

determinándose concentraciones de nitrógeno, fósforo, potasio, calcio y

magnesio. Se registró la cantidad de frutos caídos por rajado bajo la

copa de cada planta en febrero y marzo. Al momento de la cosecha, en 30

frutos por parcela experimental se evaluó: diámetro ecuatorial, espesor

de corteza, porcentaje de jugo, acidez, contenido de sólidos solubles

totales e índice de madurez. El aporte de calcio aumentó

significativamente el número de frutos por planta y disminuyó el número

de frutos caídos. Los tratamientos T3 y T4 con aporte de calcio en forma

de nitrato de calcio y el T5 con aporte de calcio y magnesio en forma

de dolomita presentaron mayores contenidos de calcio foliar respecto al

T1, que solo recibió aporte de N P K y Mg mediante fertilización con 15-

6- 15- 6.

INTRODUCCIÓNArgentina se posiciona en octavo lugar como país productor de frutas cítricas frescas 1. En la región nordeste del país se destaca la producción de naranjas y mandarinas. La mandarina 'Clementina' (Citrus reticulata

Blanco) es un cultivar muy apreciado por su sabor y precocidad.

Presenta una fruta de tamaño pequeño a mediano con cáscara fina de forma

esférica y chata por los lados 2,3.

El rajado de la fruta es un factor que condiciona la producción de

mandarinas en esta región. Esta se inicia en febrero y alcanza su máxima

incidencia en marzo, lo que coincide con la etapa de expansión de la

pulpa y el mínimo espesor de la corteza 2.

El

rajado de la fruta o splitting consiste en el agrietamiento de la

corteza que se produce en los frutos cuando están en el árbol,

generalmente antes de llegar a su maduración. El rajado se inicia

generalmente, por la zona estilar y puede evolucionar hasta la zona

ecuatorial y alcanzar la zona peduncular, pero algunas veces la ruptura

de la corteza se inicia por la zona ecuatorial de la fruta. Este

desorden fisiológico ocasiona descarte de frutas de hasta 30 % de la

producción, pero en periodos de altas precipitaciones puede representar

hasta 45 % de la fruta caída por rajado 2.

El mercado exige fruta sana, especialmente cuando se destina para

consumo en fresco y exportación. Los frutos rajados son rechazados o

depreciados económicamente, debido a que el rajado favorece la aparición

de hongos y bacterias 2,3.

En inglés, se denomina ‘cracking’ al rajado que se limita a la epidermis y ‘splitting’

al rajado que penetra en la pulpa. Esta alteración se ha detectado en

todas las zonas citrícolas y especialmente en naranja 'Navelina',

'Tangor', 'Ortanique' y mandarina 'Nova' 2.

En los frutos cítricos se presentan estos dos tipos de afecciones

fisiológicas, siendo los dos igualmente perjudiciales para la producción

y la cadena comercial 3.

Este

desorden fisiológico se atribuye a diferentes causas que se pueden

dividir en dos grupos: 1) las que inciden en la calidad de las membranas

del fruto y 2) las que generan cambios drásticos en el potencial

hídrico del fruto, produciendo un rajado profundo que penetra hasta el

interior de la pulpa 3. El factor más

mencionado por los autores es el suministro de agua a la planta, el cual

puede ocasionar fluctuaciones en el potencial hídrico del fruto 4.

Otros investigadores sugieren que el rajado es debido a la reducida

disponibilidad de calcio, potasio y boro. Sin embargo, se debe tener en

cuenta que la humedad del suelo también influye en la absorción de

elementos por parte de la planta 2,4.

El

calcio (Ca) forma parte importante de la constitución de la membrana de

las células y se acumula entre la pared celular y la lámina media, en

donde interacciona con el ácido péctico para formar pectato de calcio 5,

lo que confiere la estabilidad y mantiene la integridad de éstas. Este

nutriente, actúa como agente cementante de las células, se encuentra

estrechamente relacionado con la actividad meristemática, tiene

influencia en la regulación de los sistemas enzimáticos, la actividad de

fitohormonas y aumenta la resistencia de los tejidos a patógenos,

incrementando la vida útil poscosecha y calidad nutricional 6. La sintomatología de la deficiencia se presenta en hojas sin alcanzar su tamaño final (estadío 1:15 según escala BBCH 5), las plantas en general pierden vigor y los frutos presentan rajado de la corteza o splitting 3.

Un

suministro constante de Ca absorbido por la raíz y transferido a la

fruta es crucial para el desarrollo saludable de la misma. El transporte

a larga distancia de Ca se realiza a través de vías de xilema/apoplasto

desde la raíz hasta las partes superiores, 7,8,

y en el caso de la absorción de Ca por parte de la fruta, la expansión

de la misma también es un determinante para el flujo de entrada de savia

que entrega Ca a la fruta 9-11.

En

las células vegetales el magnesio (Mg) cumple un rol específico como

activador de enzimas incluidas en la respiración, fotosíntesis y

síntesis de ADN y ARN. También forma parte de la molécula de clorofila.

Al Mg se le atribuye participación en el desarrollo de frutos,

contribuyendo a la labor de la fructosa 1,6 difosfatasa, la cual regula

la síntesis de almidón, factor que puede ser determinante en el nivel de

azúcares y la calidad de los frutos. La carencia de este elemento

mineral se manifiesta por un amarillamiento de la hoja, que no alcanza

toda la superficie, quedando una V rellena de color verde, con su

vértice apuntando hacia el ápice de la hoja. Dada la movilidad de este

elemento en la planta, las hojas afectadas son las más viejas. Es

frecuente encontrarla en otoño e invierno, cuando el fruto ya ha

madurado y tras la recolección de éste, en variedades como ʹNavelinaʹ,

ʹSatsumaʹ y ʹSalustianaʹ, mientras que es difícil detectarla en

ʹClementinaʹ. Su origen puede deberse al antagonismo con el Ca, y sobre

todo, con el K, dosis elevadas de fertilizantes nitrogenados, que

origina una mayor absorción de K y una acumulación de P en el suelo 3.

La

deficiencia en Mg provoca defoliación prematura, reducción del

desarrollo radicular, disminución de la cosecha, frutos de menor tamaño,

con corteza delgada y fina, produciéndose mayor frecuencia de rajado en

frutos 2,3. El uso del potasio y del calcio se ha estudiado para reducir el rajado de frutos de cultivares de naranjo y mandarino 3,12.

Por

lo expuesto anteriormente, este trabajo tiene como objetivo evaluar

diferentes dosis de nitratos de calcio y carbonato de calcio y magnesio

para el control del rajado de los frutos de mandarina Clementina.

MATERIALES Y MÉTODOSCaracterísticas del loteEl

estudio se llevó a cabo durante tres campañas consecutivas 2011-2012,

2012-2013 y 2013-2014, en el Establecimiento Trébol Pampa (28º03’40’’

Latitud Sur y 58º 15’ 08’’ Longitud Oeste), Departamento de Mburucuyá,

Corrientes, Argentina. Se utilizaron plantas de mandarino (Citrus reticulata Blanco) cv. 'Clementino' injertadas sobre Poncirus trifoliata L. Raf.,

con ocho años de implantadas sobre un suelo Udipsament álfico, arenoso,

rojo amarillo podsólico, sus características químicas se visualizan en

la Tabla 1. La densidad de plantación fue de 555 plantas por hectárea en un marco de 6 x 3 metros.

La determinación cuantitativa de la MO del

suelo se realizó por el método de Walkey y Black, la del P por el método

Bray Kurtz I, el K por fotometría de llama, el Ca y el Mg por

complejometría EDTA. El pH del suelo se midió potenciométricamente en

una mezcla sólido: líquido 1:2½ (pH se determinó en agua).

El

clima del lugar se clasifica, según el sistema Köppen-Geiger, como Cfa:

Subtropical sin estación seca (verano cálido). La temperatura media

anual es 21,7 ºC, las precipitaciones anuales en promedio son de 1289

milímetros (mm) 13.

Diseño ExperimentalSe

realizó un diseño experimental de bloques completos al azar con cuatro

réplicas, utilizando una parcela experimental de cuatro plantas,

evaluándose las dos centrales.

En la Tabla 2 se describen los tratamientos aplicados en este trabajo.

En los tratamientos T1, T2, T3 y T5 se agregó urea, CO(NH2)2

que aporta en porcentaje N: 46, con el fin de corregir las dosis de N

en función de evaluar el efecto de la aplicación de Ca y Mg.

En

las tres campañas mencionadas anteriormente la aplicación de los

tratamientos se realizó en dos momentos, en marzo (50 % de la dosis de

cada tratamiento) y en septiembre (completando el 50 % restante de la

dosis por tratamiento), meses que coinciden con el crecimiento y

desarrollo de frutos y la brotación de primavera y floración

respectivamente.

Variables analizadasPara

evaluar el total de frutos afectados por rajado (TFA), en todos los

años, se contabilizó el número de frutos caídos bajo la copa de cada

planta en dos momentos, el primero, en el mes de febrero y el segundo en

el mes de marzo.

A fin de evaluar el estado

nutricional de las plantas se tomaron muestras de hojas de 8 meses de

edad en ramas fructíferas, provenientes de la brotación de primavera, y

se determinaron los contenidos de nitrógeno (N), fosforo (P), potasio

(K), calcio (Ca) y magnesio (Mg).

En el momento

de cosecha se tomaron 30 frutos al azar por parcela experimental para

determinar los caracteres de calidad de los frutos, en los que se

determinaron las siguientes variables: diámetro ecuatorial (DE) en

milímetros mediante calibre digital, espesor de corteza (EC) en

milímetros con calibre digital, porcentaje de jugo (JU) = masa del

jugo/peso de los frutos x 100, acidez titulable (AT) por volumetría de

neutralización (expresado en % de ácido cítrico), contenido de sólidos

solubles totales (SST) expresado en º Brix e índice de madurez (IM) =

SST/AT.

En el momento de la cosecha también se evaluó la producción total (Pr) en kilogramos por planta (kg planta-1) y se contabilizó el número total de frutos por planta (NFP).

Las

cosechas se llevaron a cabo en las siguientes fechas, el 31 de marzo de

2012, el 14 de marzo de 2013 y el 25 de abril de 2014.

Análisis estadísticosPara

evaluar diferencias entre los tratamientos, se realizaron análisis de

la varianza (ANOVA). Se consideró un modelo estadístico con los factores

Bloque, Año, Tratamiento y la interacción Año*Tratamiento. Se realizó

la prueba de Duncan (α≤0,05) para los tratamientos promediando los años

al no ser significativa la interacción (P-valor: 0,8093). Previo al

ANOVA, los datos fueron sometidos a las pruebas de normalidad, con el

estadístico Shapiro-Wilks modificado (α≤0,05).

Luego

se realizó un análisis de componentes principales (ACP), para

determinar el comportamiento de los tratamientos respecto a las

variables estudiadas, considerando los tratamientos como variables

clasificatorias. Se construyeron ejes artificiales que permitieron

obtener gráficos Biplot con propiedades óptimas para interpretar e

identificar asociaciones entre observaciones (tratamientos) y variables

en un mismo espacio. Todos los análisis se realizaron utilizando el

software Infostat 14.

RESULTADOS Y DISCUSIÓNEn la Tabla 3

se presentan los valores medios de las variables: total de frutos

afectados, producción total por planta y número total de frutos por

planta. Los tratamientos T5:1,5 kg pta-1 F1 + 0,720 kg pta-1 F3 y T3:1,5 kg pta-1 F1 + 0,450 kg pta-1

F2 presentaron valores significativamente menores de frutos afectados

por rajado y lograron producción y número total de frutos por planta

significativamente mayores respecto del tratamiento T1: 1,5 kg pta-1 F1. Sin embargo el tratamiento T4: 1,5 kg pta-1 F1 + 0,720 kg pta-1

F2 superó significativamente al resto de los tratamientos en las

variables producción total y número de frutos por planta, a pesar de

presentar total de frutos afectados similar al tratamiento T1:1,5 kg pta-1 F1, siendo F1: Fertilizante, que aporta en porcentaje de N:15, P2O5: 6, K2O: 15 y MgO: 6; F2: Ca(NO3)2, que aporta en porcentaje de N:16 y CaO: 26 y F3: CaMg(CO3)2 que aporta en porcentaje, MgO: 8 y CaO: 25.

El aporte de calcio tuvo incidencia positiva

sobre la producción, aumentando significativamente el número de frutos

por planta, demostrado por el menor número de frutos caídos por rajado

de la corteza. El tratamiento T5 obtuvo el menor valor de frutos

afectados y valores intermedios de producción y número de frutos por

planta. El tratamiento T1 tuvo más frutos afectados, menor producción y

número de frutos por planta, difiriendo significativamente del resto de

los tratamientos.

Estos resultados revelan que

el aporte de Ca mejora la producción y aumenta el número de frutos por

planta en mandarino 'Clementino', con menor número de frutos afectados

por rajado, resultados que coinciden con otros estudios 4,15.

Este último encontró que el efecto del calcio aplicado en forma de

sprays antes de la cosecha en cereza 'Schattenmorelle' disminuyó el

número de frutos rajados 15. Del mismo

modo en otro estudio se halló que el nitrato de calcio (4 %) y el ácido

bórico (1,5 %) fueron efectivos en la reducción del rajado de la fruta

de la granada (Punica granatum L.), aumentando la masa y el tamaño del fruto (diámetro y longitud) en comparación con el fruto de las plantas testigo 16.

También, se encontró que el aporte de Ca disminuye la incidencia del rajado de los frutos en mandarina ‘Nova’ 12. Asimismo en plantas de litchi del cultivar Mauritius tratadas con calcio en dosis de 50 y 200 mmol L-1, no se observaron frutos afectados por rajado 5.

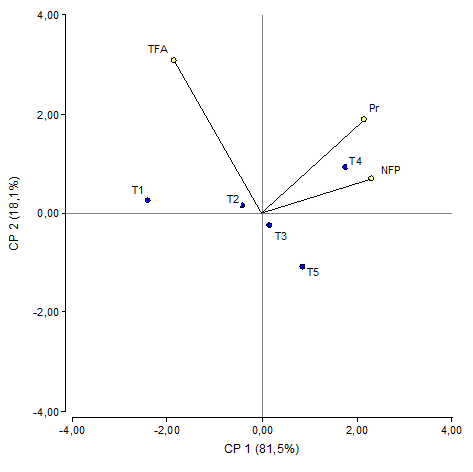

En la Figure 1

se observan las componentes principales CP1 y CP2, notándose que la CP1

explica el 81,5 % de la variabilidad total. Se visualiza asociación

entre las variables número de frutos y producción total por planta con

los tratamientos T3, T4 y T5, mientras que se asoció el total de frutos

afectados por el rajado con los tratamientos T1 y T2.

Resultados

similares se obtuvieron en tangor Murcott, donde la suplementación

foliar con N, P y K mejoró significativamente la productividad 17.

Asimismo, los resultados de este trabajo son similares a los

encontrados en mandarina Nova, donde las plantas recibieron aporte de

Ca-B y K. Las pulverizaciones con Ca-B al 0,4 y 0,6 % mostraron una

reducción significativa de la abscisión de frutos y al mismo tiempo

mayor producción 12.

Grafico

Biplot de las variables total de frutos afectados (TFA), producción

(Pr) y número de frutos por planta (NFP), en mandarino ʹClementinoʹ para

los cinco tratamientos evaluados

En la Tabla 4 se muestran

los resultados de las concentraciones foliares promedio de los

macronutrientes. Los valores obtenidos de los análisis foliares fueron

comparados con los propuestos por investigadores de nutrición de

cítricos 18. En general, los niveles

foliares de N superaron dichos valores, mientras que el resto de los

macronutrientes se encontraron por debajo de los rangos presentados 18.

El efecto de los tratamientos solo se reflejó en el contenido de calcio

foliar mientras que el resto de los nutrientes evaluados no mostraron

diferencias significativas entre aplicaciones. Los tratamientos T3 y T4

con aporte de calcio en forma de nitrato de calcio [Ca(NO3)2] y el tratamiento T5 con aporte de calcio y magnesio en forma de dolomita [CaMg(CO3)2]

presentaron mayores contenidos de calcio en hojas respecto al

tratamiento T1, que solo recibió aporte de N P K y Mg mediante

fertilización con 15- 6- 15- 6.

Resultados semejantes obtuvieron en plantas de Carica papaya fertilizadas mediante aplicaciones foliares con tres fuentes diferentes de Ca: cloruro de calcio [CaCl2], nitrato de calcio [Ca (NO3)2] y propionato de calcio [Ca(C2H5COO)2] a cuatro concentraciones (0, 60, 120 y 180 mg L−1), encontrando que a mayor concentración de Ca aplicado a las hojas mejoró la acumulación de Ca en la planta 19.

En la Tabla 5 se presentan

las variables de calidad de frutos, donde solo se encontraron

diferencias significativas en porcentaje de jugo con el mayor valor para

el tratamiento T1 y menor en T3.

Resultados

similares encontraron los autores que estudiaron el efecto de sprays de

calcio aplicados antes de la cosecha en la cereza 'Schattenmorelle' 15,

determinando que ni los sólidos solubles totales, ni la acidez total

del fruto en la cosecha se vio afectada, como así también comprobaron

que las frutas contenían más calcio que en las plantas control.

Los

resultados de este trabajo coinciden en los valores de las variables

diámetro ecuatorial, ºBrix, acidez e índice de madurez (IM) sin

diferencias significativas entre tratamientos (12). En lo que

respecta al espesor de corteza, el aporte de Ca y K promovió mayor

espesor pudiendo incidir sobre la susceptibilidad al rajado de los

frutos 12.

A la luz de estos resultados, la mayor dosis

de aplicación de nitrato de calcio logró mayor producción y número de

frutos por planta, a pesar de presentar valores intermedios de frutos

afectados por rajado. Sin embargo, la dosis intermedia de nitrato de

calcio tuvo un comportamiento similar al tratamiento con aporte de

dolomita en el total de frutos afectados, producción y número de frutos

por planta.

CONCLUSIONES

El

aporte de calcio en forma de nitrato de calcio y dolomita, disminuyó la

cantidad de frutos afectados por rajado con valores intermedios de

producción y número de frutos por planta.

La producción aumenta con el agregado de calcio en forma de nitrato, en dosis de 750 g planta-1.

Las

variables de calidad de frutos no presentan diferencias entre

tratamientos excepto en porcentaje de jugo donde se observa que con

aporte de calcio en forma de nitrato de calcio [Ca(NO3)2] aumenta significativamente respecto del testigo.

Traducir DocumentoOriginal articleControl of fruit cracking in Clementino mandarin plants

[0000-0003-3508-7794] Marco Daniel Chabbal [1] [*]

[0000-0002-0484-9736] Maria de las Mercedes Yfran-Elvira [1]

[0000-0002-9139-4759] Laura Itatí Giménez [1]

[0000-0003-2526-4881] Gloria Cristina Martínez [1]

[0000-0001-6807-8902] Lidia Agostina Llarens-Beyer [1]

[0000-0003-1559-3112] Víctor Antonio Rodríguez [1]

[1] Universidad Nacional del Nordeste (UNNE). Sargento Cabral 2131, CP 3400 Corrientes, Argentina

[*] Author for correspondence: marc.chabbal@gmail.com

ABSTRACTOne of the widest

spread physical defects limiting citrus production is the cracking of

the skin and splitting of detached fruits. The objective of this work

was to evaluate different doses of calcium nitrate and calcium and

magnesium carbonate to control the splitting fruits, the production,

nutrition and quality 'Clementine' mandarin fruits. The following

treatments was to evaluate: T1: control, T2: 225 g Ca (NO3)2, T3: 450 g Ca (NO3)2, T4: 720 g Ca (NO3)2 and T5: 720 g of CaMg (CO3)2 plant-1.They

was applied in March (50 %) and September (50 %), spring budding

period, during three consecutive seasons. Complete randomized blocks,

design with four replicates were done. All seasons, in March, foliar

samples were, for each treatment taken, for determining concentrations

of nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, calcium and magnesium. During

February and March, detached fruit under the crown of each plant was

between February and March recorded. At harvest time, 30 fruits were in

the experimental plot sampled and equatorial diameter, bark thickness,

percentage of juice, acidity, content of total soluble solids and

maturity index were measured. The contribution of calcium had a positive

effect on the production, significantly increasing the number of fruits

per plant and the fewer number of fruits that fell due to cracking of

the bark. T3 and T4 with calcium in the form of calcium nitrate and T5

with calcium and magnesium in the form of dolomite presented higher

contents of leaf calcium with respect to T1, which only received NPK and

Mg contribution through fertilization with 15- 6-15-6.

INTRODUCTIONArgentina ranks eighth as a producer of fresh citrus fruits 1. In the northeast region of the country, the production of oranges and mandarins stands out. The 'Clementina' mandarin (Citrus reticulata

Blanco) is a cultivar highly appreciated for its flavor and earliness.

It presents a small to medium-sized fruit with a thin, spherical-shaped

skin that is flat on the sides 2,3.

The cracking of the fruit is a factor that conditions the production of

mandarins in this region. It begins in February and reaches its maximum

incidence in March, which coincides with the expansion stage of the

pulp and the minimum thickness of the rind 2.

The

cracking of the fruit or splitting consists of the cracking of the bark

that occurs in the fruits when they are on the tree, generally before

reaching maturity. The splitting begins generally, by the style zone and

can evolve until the equatorial zone and reach the peduncular zone, but

sometimes the rupture of the crust begins by the equatorial zone of the

fruit. This physiological disorder causes fruit to be of up to 30 % of

production discarded, but in periods of high rainfall, it can represent

up to 45 % of the fruit that has fallen due to cracking 2.

The market demands healthy fruit, especially when it is intended for

fresh consumption and export. Cracked fruits are rejected or

economically depreciated, since cracking favors the appearance of fungi

and bacteria 2,3.

In English, 'cracking' is called the cracking that is limited to the epidermis and 'splitting'

the cracking that penetrates the pulp. This alteration has been

detected in all citrus areas and especially in 'Navelina' orange,

'Tangor', 'Ortanique' and 'Nova' mandarin 2.

In citrus fruits these two types of physiological conditions occur,

both being equally harmful to production and the commercial chain 3.

This

physiological disorder is attributed to different causes that can be

divided into two groups: 1) those that affect the quality of the fruit

membranes and 2) those that generate drastic changes in the water

potential of the fruit, producing a deep crack that penetrates to the

interior of the pulp 3. The factor most

mentioned by the authors is the water supply to the plant, which can

cause fluctuations in the water potential of the fruit 4.

Other researchers suggest that the cracking is due to the reduced

availability of calcium, potassium and boron. However, it should be

taken into account that soil moisture also influences the absorption of

elements by the plant 2,4.

Calcium

(Ca) forms an important part of the constitution of the cell membrane

and accumulates between the cell wall and the middle lamina, where it

interacts with pectic acid to form calcium pectate 5,

which confers stability and maintains the integrity of these. This

nutrient acts as a cementing agent for cells, it is closely to

meristematic activity related, and has an influence on the regulation of

enzyme systems, phytohormone activity and increases tissue resistance

to pathogens, increasing postharvest shelf life and nutritional quality 6. The symptoms of the deficiency appear in leaves without reaching their final size (stage 1:15 according to the BBCH scale 5), the plants in general lose vigor and the fruits show cracking of the bark or splitting 3.

A

constant supply of Ca absorbed by the root and transferred to the fruit

is crucial for healthy fruit development. The long-distance transport

of Ca is carried out through xylem/apoplast pathways from the root to

the upper parts 7,8,

and in the case of the absorption of Ca by the fruit, the expansion of

the It is also a determinant for the inflow of sap that delivers Ca to

the fruit 9-11.

In

plant cells, magnesium (Mg) plays a specific role as an activator of

enzymes included in respiration, photosynthesis, and DNA and RNA

synthesis. It is also part of the chlorophyll molecule. Mg is attributed

participation in the development of fruits, contributing to the work of

fructose 1,6 diphosphatase, which regulates the synthesis of starch, a

factor that can be a determining factor in the level of sugars and the

quality of the fruits. The lack of this mineral element is by a

yellowing of the leaf manifested, which does not reach the entire

surface, leaving a green filled V, with its vertex pointing towards the

apex of the leaf. Given the mobility of this element in the plant, the

affected leaves are the oldest. It is common to find it in autumn and

winter, when the fruit has already matured and/or after its collection,

in varieties such as ʹNavelinaʹ, ʹSatsumaʹ and ʹSalustianaʹ, while it is

difficult to detect it in ʹClementinaʹ. Its origin may be due to

antagonism with Ca, and especially with K, high doses of nitrogen

fertilizers, which cause a greater absorption of K and an accumulation

of P in the soil 3.

The

Mg deficiency causes premature defoliation, reduced root development,

reduced harvest, smaller fruits, with thin and fine rind, producing a

higher frequency of cracking in fruits 2,3. The use of potassium and calcium has been studied to reduce fruit cracking of orange and mandarin cultivars 3,12.

Due

to the above, this work aims to evaluate different doses of calcium

nitrates and calcium and magnesium carbonate to control the cracking of

Clementine mandarin fruits.

MATERIALS AND METHODSLot characteristicsThe

study was carried out during three consecutive campaigns 2011-2012,

2012-2013 and 2013-2014, in the Trébol Pampa Establishment (28º03'40 ''

South Latitude and 58º 15 '08' 'West Longitude), Department of

Mburucuyá, Corrientes, Argentina. Mandarin plants (Citrus reticulata Blanco) cv. 'Clementino' grafted on Poncirus trifoliata L. Raf., with eight years of implantation on a soil Udipsament alphic, sandy, red yellow podsolic, their chemical characteristics are displayed in Table 1. The planting density was 555 plants per hectare in a 6 x 3 meter frame.

The quantitative determination of the OM

of the soil was carried out by the Walkey and Black method, that of P by

the Bray Kurtz I method, K by flame photometry, Ca and Mg by EDTA

complexometry. Soil pH was measured potentiometrically in a 1: 2½ solid:

liquid mixture (pH was determined in water).

The

climate of the place is classified, according to the Köppen-Geiger

system, as Cfa: Subtropical without dry season (hot summer). The mean

annual temperature is 21.7 ºC; the average annual rainfall is 1289

millimeters (mm) 13.

Experimental designAn

experimental design of complete random blocks with four replications

was carried out, using an experimental plot of four plants, evaluating

the two plants.

In Table 2 the experiment applied were described in this work.

In treatments T1, T2, T3 and T5, urea, CO (NH2)2

was added, which contributes in percentage N: 46, in order to correct

the doses of N in order to evaluate the effect of the application of Ca

and Mg.

In the three campaigns mentioned above,

the application of the treatments was carried out in two moments, in

March (50 % of the dose of each treatment) and in September (completing

the remaining 50 % of the dose per treatment), months that coincide with

the fruit growth and development and spring budding and flowering

respectively.

Variables analyzedTo

evaluate the total number of fruits affected by cracking (TFA), in all

years, the number of fallen fruits under the canopy of each plant was at

two times counted, the first in February and the second in the month of

March.

In order to evaluate the nutritional

status of the plants, samples of 8-month-old leaves were taken in

fruiting branches, coming from spring budding, and the contents of

nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), potassium (K ), calcium (Ca) and magnesium

(Mg).

At harvest time, 30 random fruits were

taken per experimental plot to determine the quality characters of the

fruits. The following variables were determined: equatorial diameter

(ED) in millimeters by digital caliper, bark thickness (BTH) in

millimeters with digital caliper, juice percentage (JU) = juice

mass/fruit weight x 100, titratable acidity (TA) by neutralization

volumetry (expressed in % of citric acid), content of total soluble

solids (TSS) expressed in ºBrix and maturity index (MI) = SST/TA.

At the time of harvest, the total production (Pr) in kilograms per plant (kg plant-1) was also evaluated and the total number of fruits per plant (NFP) was counted.

The harvests were carried out on the following dates, March 31, 2012, March 14, 2013 and April 25, 2014.

Statistical analysisTo

evaluate differences between treatments, analysis of variance (ANOVA)

was performed. A statistical model was considered with the factors

Block, Year, Treatment and the interaction Year*Treatment. Duncan's test

(α≤0.05) was performed for the treatments averaging the years as the

interaction was not significant (P-value: 0.8093). Prior to ANOVA, the

data were subjected to normality tests, with the modified Shapiro-Wilks

statistic (α≤0.05).

Then a principal component

analysis (PCA) was carried out to determine the behavior of the

treatments with respect to the variables studied, considering the

treatments as classificatory variables. Artificial axes were constructed

that allowed obtaining Biplot graphs with optimal properties to

interpret and identify associations between observations (treatments)

and variables in the same space. All analyzes were performed using the

Infostat software 14.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Table 3 shows the mean values of the variables:

total affected fruits, total production per plant and total number of

fruits per plant. Treatments T5: 1.5 kg pta-1 F1 + 0.720 kg pta-1 F3 and T3: 1.5 kg pta-1 F1 + 0.450 kg pta-1

F2 presented significantly lower values of fruits affected by cracking

and achieved production and total number of fruits per plant

significantly higher with respect to treatment T1: 1.5 kg pta-1 F1. However, treatment T4: 1.5 kg pta-1 F1 + 0.720 kg pta-1

F2 significantly exceeded the rest of the treatments in the variables

total production and number of fruits per plant, despite presenting

total affected fruits similar to treatment T1: 1.5 kg pta-1 F1. F1 acted as a fertilizer, which contributes in percentage of N: 15, P2O5: 6, K2O: 15 and MgO: 6; F2: Ca (NO3)2. The latter contributes in percentage of N: 16 and CaO: 26 and F3: CaMg (CO3)2 that contributes in percentage, MgO: 8 and CaO: 25.

The calcium contribution had a positive

impact on production, significantly increasing the number of fruits per

plant, shown by the lower number of fallen fruits due to cracking of the

bark. Treatment T5 obtained the lowest value of affected fruits and

intermediate values of production and number of fruits per plant.

Treatment T1 had more affected fruits, lower production and number of

fruits per plant, differing significantly from the rest of the

treatments.

These results reveal that the

contribution of Ca improves production and increases the number of

fruits per plant in 'Clementino' mandarin, with fewer fruits affected by

cracking, results that coincide with other studies 4,15.

It

was found that the effect of calcium applied in the form of sprays

before the harvest in 'Schattenmorelle' cherry decreased the number of

cracked fruits 15. Similarly, in another

study it was found that calcium nitrate (4 %) and boric acid (1.5 %)

were effective in reducing the cracking of the pomegranate fruit (Punica granatum L.), increasing the mass and the size of the fruit (diameter and length) in comparison with the fruit of the control plants 16.

In addition, it was found that the contribution of Ca decreases the incidence of fruit cracking in 'Nova' mandarin 12. Likewise, in lychee plants of the cultivar Mauritius treated with calcium in doses of 50 and 200 mmol L-1, no fruits affected by cracking were observed 5.

In Figure 1,

the main components PC 1 and PC 2 are observed, noting that PC 1

explains 81.5 % of the total variability. An association between the

variables number of fruits and total production per plant with

treatments T3, T4 and T5 is visualized, while the total of fruits

affected by cracking was associated with treatments T1 and T2.

Similar results were obtained in Murcott tangor, where foliar supplementation with N, P and K significantly improved productivity 17.

Likewise, the results of this work are similar to those found in Nova

mandarin, where the plants received a contribution of Ca-B and K. The

sprays with Ca-B at 0.4 and 0.6 % showed an abscission significant

reduction of fruits and at the same time higher production 12.

Biplot

graph of the variables total of affected fruits (TFA), production (Pr)

and number of fruits per plant (NFP), in ʹClementino ʹ mandarin for the

five treatments evaluated

Table 4 shows the results of the average foliar

concentrations of the macronutrients. The values obtained from the

foliar analyzes were compared with those proposed by citrus nutrition

researchers 18. In general, the foliar

levels of N exceeded these values, while the rest of the macronutrients

were found below the ranges presented 18.

The effect of the treatments was only reflected in the foliar calcium

content while the rest of the nutrients evaluated did not show

significant differences between applications. Treatments T3 and T4 with

calcium nitrate [Ca (NO3)2] and treatment T5 with calcium and magnesium dolomite [CaMg (CO3)2]

contained higher calcium content in leaves. Regarding the T1 treatment,

which only received NPK and Mg by fertilization with 15-6-15-6.

Similar results were obtained in Carica papaya plants fertilized by foliar applications with three different sources of Ca:calcium chloride [CaCl2], calcium nitrate [Ca (NO3)2] and calcium propionate [Ca (C2H5COO)2]. This was applied using four concentrations (0, 60, 120 and 180 mg L-1), finding that the higher the concentration of Ca applied to the leaves, the accumulation of Ca in the plant improved 19.

Table 5 shows the fruit quality variables, where

only significant differences were found in the percentage of juice with

the highest value for the T1 treatment and the lowest in T3.

Similar

results were found by the authors who studied the effect of calcium

sprays applied before harvest in the 'Schattenmorelle' cherry 15,

determining that neither the total soluble solids, nor the total

acidity of the fruit at harvest was affected, as thus they also verified

that the fruits contained more calcium than in the control plants.

The

results of this work coincide in the values of the variables equatorial

diameter, ºBrix, acidity and maturity index (MI) without significant

differences between treatments 12.

Regarding the thickness of the bark, the contribution of Ca and K

promoted greater thickness, which could affect the susceptibility to

cracking of the fruits 12.

In light of these results, the higher

application dose of calcium nitrate achieved higher production and

number of fruits per plant, despite presenting intermediate values of

fruits affected by cracking. However, the intermediate dose of calcium

nitrate had a similar behavior to the treatment with dolomite

contribution in the total of affected fruits, production and number of

fruits per plant.

CONCLUSIONS

The

contribution of calcium in the form of calcium nitrate and dolomite

decreased the amount of fruits affected by cracking with intermediate

production values and number of fruits per plant.

Production increases with the addition of calcium in the form of nitrate, in doses of 750 g plant-1.

The

fruit quality variables do not show differences between treatments

except in the percentage of juice where it is observed that with the

contribution of calcium in the form of calcium nitrate [Ca (NO3)2] it increases significantly compared to the control.