Translate PaperArticulo originalAnálisis de diversos aspectos económicos de la producción en huertas de nogales de alta y baja densidad. Estudio de caso

[0000-0003-3295-3167] Margarita Fernández-Chávez [1]

[0000-0002-3447-7267] Sergio Guerrero-Morales [1]

[0000-0001-7919-5709] Abdón Palacios-Monárrez [1]

[0000-0002-5872-6360] Luisa Patricia Uranga-Valencia [1]

[0000-0003-4869-9204] Laura Escalera-Ochoa [1]

[0000-0002-9211-0797] Sandra Pérez-Álvarez [1] [*]

[*] Autor para correspondencia: spalvarez@uach.mx

RESUMENEl cultivo de

nuez pecana, es una de las actividades económicas más importantes en

Chihuahua, México. En los últimos años, el precio de la nuez ha

aumentado originando una alta rentabilidad, lo que ha motivado al

establecimiento de nuevos huertos, con altas densidades (204 árboles por

hectárea). Sin embargo, hasta la fecha, no existe información económica

confiable que respalde que el cultivo en altas densidades es mejor que

en las bajas. Por esta razón, el objetivo de esta investigación fue

analizar económicamente la producción de huertos de nuez cultivadas en

alta y baja densidad. En este estudio, se utilizó un enfoque de

investigación cuantitativa y la información requerida fue recolectada

por medio de 66 encuestas (tres por cada año de los 11 analizados de

plantaciones de baja y alta densidad) realizadas a los productores de

nuez con plantaciones de alta y baja densidad (seis productores por

año). De la información de las encuestas, se determinaron los costos de

producción y los ingresos por venta de cosecha. Los resultados obtenidos

indican que los costos de producción en los primeros cuatro años fueron

mayores en las bajas densidades, que en las altas densidades. El

rendimiento por nuez, por nogal, a partir del octavo año, fue mayor en

bajas densidades que en altas densidades y el rendimiento por hectárea

fue mayor en altas densidades, por el mayor número de nogales (nueces

por hectárea) que se plantan en altas densidades. La relación costo

beneficio fue mayor en bajas densidades que en altas densidades. Hasta

la fecha no hay información sobre la producción de nuez en baja y alta

densidad, por lo que este estudio es importante para los agricultores,

especialmente en México.

INTRODUCCIÓNEl cultivo de la nuez (Carya illinoensis

Koch) es uno de los más importantes en la región agrícola ciudad de

Delicias, Chihuahua. El nogal pecanero es originario del sureste de los

Estados Unidos de América y el norte de México. El cultivo de la nuez

comenzó en el estado de Chihuahua hace unos cuatrocientos años, en el

valle de Allende, con árboles criollos 1.

Las nueces son un producto perecedero, ya que contienen un alto

porcentaje de aceite (70-75 %), 12-15 % de carbohidratos, 9-10 % de

proteínas, 1,5 % de minerales y 5 % de agua 2.

En relación a la producción mundial de nuez, México produce cerca del 38 % 3

y a nivel nacional esto ha aumentado alrededor del 80 % en los últimos

trece años (2003 a 2015) alcanzando alrededor de 110 mil toneladas 4, de las cuales Chihuahua produce el 65 % 5.

COMENUEZ, una entidad mexicana de productores de nueces respaldada por

SAGARPA considera que la producción de nueces de México podría alcanzar

las 149,685 toneladas para el año 2025 6.

En el estado de Chihuahua, predominan las plantaciones de nogal con diferentes distancias (6x6 m a 30x30 m) 7,8;

sin embargo, las altas densidades favorecen altos rendimientos en los

primeros años, pero también se incrementan los costos de producción y

una disminución del rendimiento por ha-1 después de los 10 años de establecidos.

El

nogal pacanero requiere grandes cantidades de luz para tener una alta

eficiencia fotosintética, por lo que el sombreado reduce

significativamente el crecimiento estacional del brote y tiene un efecto

negativo en la producción, estabilidad y calidad de la nuez 9.

Al respecto otros autores mencionan que densidades altas de nogal

provoca poca recepción de luz por el sombreado de los árboles ya que hay

entrelazamiento de ramas, reduciéndose la cantidad de luz

fotosintéticamente activa recibida por área de hoja de nogal 10.

Por lo anterior, los azucares no se acumulan, el crecimiento se afecta,

originando que el porcentaje de la almendra disminuya. Finalmente se

produce una reducción considerable en la producción de nuez por árbol,

obteniéndose rendimientos bajos por hectárea y una baja calidad de la

nuez 10. De manera similar algunos autores

mencionan que establecer altas densidades de nogal producirá altos

rendimientos por hectárea en los primeros años de producción, lo que

permitirá incrementar considerable mente un beneficio económico a los

productores de nuez 11. Sin embargo, lo

que no se ha informado, quizás por desconocimiento, es que en huertas

con altas densidades (204 nogales por hectárea o más) se presentarán

problemas de sombreado después de 10 años o más de establecidos,

disminuyendo el rendimiento.

En los últimos años

el precio de la nuez se ha incrementado considerablemente, originando

una alta rentabilidad de las huertas nogaleras. Lo anterior, ha motivado

a varios productores al establecimiento de nuevas huertas. Algunas de

estas se están estableciendo a altas densidades (204 nogales por

hectárea); es decir, a distancias entre nogales e hileras de siete

metros. Sin embargo, los productores se encuentran con la realidad de

que no existe información económica confiable que les permita decidir

cuál es la mejor densidad de nogal en las nuevas plantaciones y poder

obtener en un futuro los mejores ingresos. Por lo anterior, el objetivo

del presente estudio fue analizar algunos aspectos económicos en huertas

de nogal de alta y baja densidad.

MATERIALES Y MÉTODOSEn

el presente estudio de caso se utilizó un enfoque integral

investigativo cuali-cuantitativo, debido a que se refiere a

investigaciones sistemáticas y empíricas de los diferentes tipos de

plantaciones de nogal, su manejo y su productividad. El tipo de

investigación fue conclusiva y descriptiva, ya que describen los

sistemas de plantación utilizados y el cultivo de alfalfa intercalado

entre nogales (en bajas densidades).

Los nogales

en la ciudad de Delicias, Chihuahua se siembran en una gran variedad de

suelos, siendo los más utilizados los francoarcilloarenosos con un pH

ligeramente alcalino, profundos, con buen drenaje y con bajo contenido

de materia orgánica. El clima en la región es extremo, semiárido, pocas

precipitaciones, temperaturas muy altas en el verano (40-41 ℃) y bajas

en el invierno (-5 a -6 ℃) 12.

Se

analizaron huertas desde un año, hasta 11 de establecidas, en baja y

alta densidad y se utilizó la técnica de revisión analítica, para lo

cual la información se obtuvo por medio de 66 encuestas, de variables

como: inversión inicial, costos variables (aplicación de fertilizantes,

agroquímicos y foliares, podas y riegos), costos fijos (número de

árboles plantados) e ingreso por venta de nogal pecanero, en producción y

de cosecha de alfalfa entre los nogales. Se estableció como baja

densidad el marco de plantación de 10 x 10 m (100 árboles ha-1) y alta densidad, el marco de plantación de 7 x 7 m (204 árboles ha-1).

Como

indicador para determinar la mejor plantación económicamente, en los

primeros 11 años después de su establecimiento, se utilizó la relación

Beneficio-Costo (B/C), esta relación se obtiene dividiendo el ingreso de

nogal por hectárea, entre el costo de producción de nogal por hectárea y

periodo de recuperación de la inversión de los dos sistemas de

producción estudiados.

Para la determinación de

los costos de producción del nogal, se consideró el costo de las labores

de establecimiento en el primer año, riegos, fertilización, control de

plagas, enfermedades, eliminación de maleza y cosecha. Para lo anterior,

se utilizó la metodología propuesta por Fideicomisos Instituidos en

Relación con la Agricultura 13, que es un

sistema para la determinación de costos de producción en cultivos

agrícolas y frutícolas. El costo de producción de alfalfa, se determinó

considerando todas las labores que se realizan en dicho cultivo 14.

El proceso de recopilación de información se realizó a través de 66

encuestas (tres por cada año de los 11 años analizados de las huertas,

de baja y alta densidad) y entrevistas a productores de nuez (seis por

año). La población considerada en el estudio fue de productores que en

el 2018 contaban con una huerta establecida con alta o baja densidad de

uno a 11 años de plantación, en los municipios de Saucillo, Delicias,

Rosales, Meoquí y Julimes, del estado de Chihuahua, México.

La

unidad de análisis para la investigación fue determinar económicamente

cuál es la mejor plantación de nogal, por ello se analizaron los costos

de establecimiento, manejo o labores e ingreso por la producción de

altas y bajas densidades de nogal para comparar ingresos económicos de

ambos sistemas 13. Para obtener el

rendimiento de nuez por hectárea, se utilizó el rendimiento de nuez por

nogal, informado por cada productor encuestado, posteriormente se

multiplicó por el número de nogales, de acuerdo al marco de plantación,

para obtener el rendimiento por hectárea. Se seleccionaron las huertas

que cumplieran las características de ambas densidades, años de

plantación de la huerta y establecimiento de alfalfa, como segundo

cultivo entre las hileras de nogales (en plantaciones a baja densidad).

La

recopilación de la información se realizó entre los meses de octubre -

diciembre 2018 a través de encuestas a productores de nogal con huertas

establecidas en ambas densidades.

Una vez

obtenida la información, esta se organizó, se analizó y se determinaron

los costos de producción e ingreso por año. Se realizaron las gráficas y

tablas requeridas para la explicación de la información, utilizando el

programa Excel, se determinó el tiempo de recuperación de la inversión

en ambas densidades estudiadas, así como la relación Beneficio-Costo por

año y la obtenida de los costos e ingresos totales a los 11 años

después de su establecimiento.

Para el análisis

estadístico los datos se sometieron a un análisis de varianza simple.

Las diferencias entre las medias de los tratamientos se compararon

mediante la prueba de Tukey (p<0,05). Para el análisis se utilizó el

paquete estadístico Statgraphics 5.1 (2001).

RESULTADOS Y DISCUSIÓNCostos de producción por hectárea de nogales en baja y alta densidadSobre

la base de los resultados de las encuestas realizadas a los

productores, así como a la consulta de información de fuentes oficiales,

sobre el establecimiento y la gestión de los huertos, fue posible

determinar el costo del establecimiento y la gestión de ambos sistemas

de producción por hectárea (Figura 1).

Costos de establecimiento y manejo de huertas de alta y baja densidad por hectárea en cada uno de los 11 años de estudio

Fuente: FCAyF-UACH.2019

Análisis del establecimiento de producción de huertas de alta y baja densidad de nogal

En el primer año de establecimiento de la

huerta, el mayor costo de inversión fue en la plantación de baja

densidad más el cultivo de la alfalfa, con un costo de $ 69157,00, en

cambio en la huerta de alta densidad se generó un costo de $ 64764,00.

En la Figura 1 se puede apreciar que en los primeros

cuatro años es mayor el costo de establecimiento y manejo en huertas de

bajas densidades, que el costo y el manejo de las huertas de altas

densidades. A partir del quinto año las huertas de altas densidades

causan el mayor costo de manejo en comparación con las huertas de bajas

densidades. Este resultado no coincide con el obtenido en otras

investigaciones 15, donde la plantación de

alta densidad, de frutales que duran menor tiempo que el nogal para

producir, alcanzan la producción total en el cuarto año y también tuvo

la proporción más alta (>80 %) de frutas que fueron mejores, tanto en

términos de calidad como de precio. Otro resultado que no coincide con

el obtenido en esta investigación fue en ciruela (Prunus domestica L.) donde los costos de establecimiento fueron 1,9 veces mayores en la huerta de alta densidad (7,729 € ha-1) que en la de baja densidad (€ 4,069,3 ha-1), aunque la inversión se recuperó entre el segundo y el tercer año de producción 16.

En el cultivo del mango (Mangifera indica

L.) es improbable que la productividad se incremente mediante el uso de

plantaciones de alta densidad, sin grandes esfuerzos en el mejoramiento

de plantas y el manejo de las copas 17.

En el caso específico del nogal, la poda es un aspecto básico a tener en

cuenta para incrementar los rendimientos, aún más en las huertas de

alta densidad.

El mayor costo generado en el año

de establecimiento y los siguientes tres años en las huertas de nogal

de baja densidad se atribuye al costo de producción del cultivo de

alfalfa intercalada en el sistema de bajas densidades, ya que del total

del gasto del primer año ($ 69157,00), el costo del establecimiento y el

manejo de alfalfa corresponde a $ 39533,00, esto representa el 57 % del

costo total de este sistema de producción de baja densidad. En

contraste la plantación y el manejo del nogal generan un costo total de $

29624,00, lo cual representa el 43 % del costo total del sistema de

producción. En el segundo, el tercero y el cuarto año, el costo del

manejo de la alfalfa nuevamente fue el que incrementó el costo del

sistema de bajas densidades, siendo 85,7, 75,4 y 71,6 %,

respectivamente, mientras que el manejo del nogal solamente representó

el 14,3, 24,6 y 28,4 % del costo total. El incremento en el costo de

producción del nogal, a partir del segundo año, se atribuye a que

conforme el nogal va creciendo requiere mayores cantidades de insumos

como fertilizantes, insecticidas y gasto en podas.

A

partir del quinto año en el sistema de producción de bajas densidades,

los nogales por su crecimiento ocupan mayor espacio, originando mucha

sombra, que no permite el desarrollo de otro cultivo entre los nogales y

a partir de esta fecha los costos fueron generados sólo por el manejo

del nogal. Al hacer la comparación de los costos generados por altas y

bajas densidades se aprecia en la figura 1 que las huertas de altas

densidades al quinto año generaron un mayor costo que las de bajas

densidades, en $ 10,086 y se incrementó paulatinamente en los siguientes

años del frutal. Al décimo año el costo de producción de altas

densidades fue mayor en $ 20,092, con respecto al costo de producción de

bajas densidades del nogal. Este incremento en los costos se debió a

una mayor cantidad de fertilizantes, insecticidas, podas, cosecha y

riegos, debido al mayor número de árboles.

Según

investigaciones realizadas el uso de plantaciones de alta densidad en

huertos es un concepto innovador para aumentar la productividad sin

alterar la calidad de las frutas, incluso cuando estos huertos necesitan

una mayor inversión, en comparación con los convencionales 15, es útil aplicar el concepto porque pueden proporcionar rendimientos más rápidos y mejores sobre los fondos invertidos.

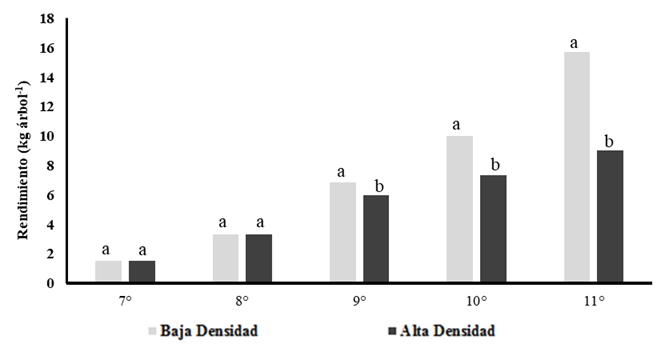

Rendimiento de nuez por árbol y hectárea en bajas y altas densidades de nogalEl

nogal empieza su producción a partir del quinto año. Considerando que

cada productor le da su propio manejo a la huerta, de acuerdo a su

conocimiento, experiencia o asesor, se puede decir que existe una gran

diversidad de manejos que puede producir diferentes rendimientos; sin

embargo, son menos de 20 nueces por nogal las que produce en su primer

año de ensayo, el número de nueces se incrementa para el sexto año de

edad, pero no es significativo su rendimiento. A partir del séptimo año,

de acuerdo con los resultados de la encuesta, el nogal produce en

promedio 1,5 kg de nuez por árbol e incrementa su rendimiento, de

acuerdo al manejo que recibe en la huerta, aún cuando el manejo que se

les da depende del productor.

En huertas de bajas densidades (100 nogales por ha-1),

se encontró que árboles de ocho años tienen una producción de 3,34 kg,

en promedio, este rendimiento se incrementa a 6,85 kg en el noveno año y

a 10 kg en el décimo año. En huertas de altas densidades hasta el

séptimo año no existe competencia de luz entre los árboles de nogal; por

lo tanto, su potencial de rendimiento (1,5 kg) es igual a los árboles

establecidos en bajas densidades. Sin embargo, a partir del octavo año

el rendimiento por árbol tiende a disminuir, en relación con los árboles

plantados a 10 x 10 metros con un rendimiento de 3,33 kg. El

rendimiento a los nueve años es de 6 kg, este rendimiento se sigue

incrementando en promedio a 7,35 kg y 9 kg en el décimo y onceavo año,

respectivamente. Estos rendimientos de los últimos tres años, son

menores a los rendimientos que producen nogales de la misma edad en

bajas densidades (Figura 2). Este menor rendimiento se atribuye a lo mencionado por otros autores 10,

que el sombreado de hojas ocasiona una menor eficiencia fotosintética,

que afecta negativamente el rendimiento, retención de frutos y

producción de yemas florales.

Rendimiento de nuez por árbol y análisis económico del establecimiento y producción de huertas de alta y baja densidad de nogal

Fuente: FCAyF-UACH, 2019

En la investigación, análisis del establecimiento de producción de huertas de alta y baja densidad de nogal

El menor rendimiento que se obtiene a

partir del noveno año en la huerta de alta densidad se atribuye a que, a

partir de esta fecha, las ramas entre nogales vecinos se entrelazan,

provocando una menor penetración de luz a las hojas internas del nogal.

Esta baja cantidad de luz recibida por las hojas internas del nogal

tiene un efecto negativo en la fotosíntesis del árbol y por consecuencia

se afecta el rendimiento, ocasionándose una disminución de este, como

ha sido informado 10..Al realizar la estimación de rendimientos por hectárea (Figura 3),

se encontró que a partir del séptimo año hasta el onceavo año el

rendimiento es mayor cuando se tiene la densidad de 204 árboles (alta

densidad).

Rendimiento

de nuez por hectárea y análisis económico del establecimiento y

producción de huertas de alta y baja densidad de nogal

Fuente: FCAyF-UACH.2019

En la investigación, análisis del establecimiento de producción de huertas de alta y baja densidad de nogal

El mayor rendimiento en la alta densidad se

obtiene porque en esta existe más del doble de nogales que en la baja

densidad. También se aprecia que en el séptimo y octavo año el

rendimiento en altas densidades es el doble del rendimiento en bajas

densidades. En el onceavo año se obtiene un mayor rendimiento en altas

densidades de 230 kg ha-1 con respecto a las bajas

densidades, aunque no existen diferencias significativas. Lo anterior se

atribuye a que a partir del noveno año el rendimiento por árbol en

altas densidades tiende a disminuir por efectos del sombreado, que causa

una menor fotosíntesis, disminución de emisión de yemas florales y

caída de nueces 10.

En

otra investigación se estudiaron tres variedades de almendras en baja y

alta densidad y los autores encontraron que el rendimiento por árbol de

la nuez fue mayor en baja densidad, pero el rendimiento por hectárea

fue superior en alta densidad 18, esto fue

debido a la existencia de un mayor número de árboles por hectárea. Este

resultado coincide con el de esta investigación, donde el mayor

rendimiento por hectárea también se obtuvo en altas densidades. Lo

anterior, es muy importante en los primeros años de producción del nogal

y uno de los objetivos de los productores, es obtener mayores

rendimientos por hectárea, con el fin de lograr mayores ingresos.

En

relación al mayor rendimiento por árbol en las bajas densidades, que en

las altas, este se atribuye a que en bajas densidades el árbol, tiene

un mayor espacio y recibe más luz, lo que causa una mayor fotosíntesis y

mayor rendimiento. En este tema, algunos autores establecieron que el

crecimiento aumenta, de acuerdo con la mayor accesibilidad 19; es decir, en bajas densidades.

Relación beneficio-costo por hectárea en bajas y altas densidades de nogalLa

Relación Beneficio-Costo (B/C) siempre se desea que sea mayor a uno, al

ser de esta forma se indica que se está generando una ganancia mayor a

la inversión realizada en la actividad que se está practicando. En la

producción de nogal con bajas y altas densidades se empezó a analizar la

relación B/C, a partir del primer año en las huertas de bajas

densidades. El primer año, a pesar de que la alfalfa generó un ingreso

de $ 51408,00 pesos, la relación B/C fue de 0,74, una relación negativa,

debido a que se consideró el costo de establecimiento de la huerta y de

la alfalfa. A partir del segundo año, la relación B/C, fue mayor de uno

hasta el cuarto año, mientras que en las huertas de altas densidades,

al no generar ingresos, no se obtiene una relación B/C. La buena

relación B/C obtenida en los primeros años en huertas de bajas

densidades se atribuye al ingreso que genera el cultivo de la alfalfa,

ya que en estos años el nogal no produce. A partir del séptimo año, que

es cuando el nogal empieza a tener producción comercial, se analiza la

relación B/C generada por los ingresos. La producción en ambas

densidades es baja y el costo de manejo es mayor que el ingreso

obtenido, lo que genera que se obtenga una relación B/C menor a uno,

siendo mucho menor del séptimo al noveno año en huertas con baja

densidad. La mayor relación B/C obtenida en estos años en las huertas de

altas densidades se atribuye a una mayor producción de nuez, ocasionada

por el mayor número de árboles por hectárea que en las huertas de bajas

densidades (Tabla 1).

Hasta la fecha no existe información en

este tema en nogal, siendo esta la primera investigación de este tipo,

de aquí la importancia de los resultados que se presentan. Se resalta la

relevancia de intercalar la alfalfa con nogal en bajas densidades en

los primeros cuatro años de establecida la huerta, ya que permite

generar ingresos que ayudan al mantenimiento de la huerta de nogal, no

siendo esto posible en las huertas de altas densidades, que no generan

ingresos en estos años. Sin embargo, es importante resaltar, que, en los

primeros años de producción del nogal, las huertas con altas

densidades, a pesar de tener mayores costos de producción que huertas de

bajas densidades, generan una mejor relación B/C. Lo anterior, debido

al mayor número de nogales en altas densidades. En ambas densidades de

nogal estudiadas, el décimo y onceavo año después del establecimiento,

se genera una relación B/C mayor a dos. Esto indica que en estos años y

en los posteriores, debido al alto rendimiento y el precio de venta de

la nuez, el ingreso por hectárea será muy benéfico para los productores,

que podrán recuperar lo invertido en los primeros años y obtener

ganancias.

Resultados similares a los de esta

investigación fueron informados en otras investigaciones realizadas en

una plantación de mango 20, donde la

relación B/C fue de 1,49 y 2,00 en densidad tradicional y alta,

respectivamente y la tasa interna de rendimiento fue mayor en las

plantaciones de alta densidad que en la tradicional 20.

Un resultado similar pero referido al ingreso se obtuvo en el cultivo

de palma, donde el análisis indicó que el ingreso máximo se podía

obtener en alta densidad, en comparación con el convencional 21.

En nogal no hay información sobre estudios de relación B/C, siendo esta

investigación la primera que compara plantaciones de alta y baja

densidad.

CONCLUSIONES

Los

resultados obtenidos indican la importancia de establecer las bajas

densidades de nogal intercalado con alfalfa, para la obtención de

ingresos que ayudan a solventar los costos del manejo de las huertas de

nogal. Considerando el rendimiento de nogal por árbol, es mejor las

huertas con bajas densidades (100 nogales por hectárea) que las de altas

densidades (204 nogales por hectárea). En las huertas de bajas

densidades cada árbol, a partir del octavo año, produce un mayor

rendimiento que los árboles de huertas de altas densidades.

La

relación B/C general más alta se logró en plantaciones de baja densidad

en comparación con la alta densidad. El período de recuperación de la

inversión fue primero en huertos de baja densidad (11 años), en

comparación con los huertos de alta densidad, donde no hay recuperación

de la inversión durante este mismo período analizado. En huertos de baja

densidad en el onceavo año, se obtuvo una ganancia de $ 74590,00,

mientras que las altas densidades tenían un déficit de $ 45325,00.

Traducir DocumentoOriginal articleAnalysis of various economic production aspects in high and low density walnut orchards. Case study

[0000-0003-3295-3167] Margarita Fernández-Chávez [1]

[0000-0002-3447-7267] Sergio Guerrero-Morales [1]

[0000-0001-7919-5709] Abdón Palacios-Monárrez [1]

[0000-0002-5872-6360] Luisa Patricia Uranga-Valencia [1]

[0000-0003-4869-9204] Laura Escalera-Ochoa [1]

[0000-0002-9211-0797] Sandra Pérez-Álvarez [1] [*]

[1] Facultad

de Ciencias Agrícolas y Forestales. Universidad Autónoma de Chihuahua,

km 2.5, Delicias, carretera a Rosales. Campus Delicias. Código Postal

33000. Delicias, Chihuahua, México

[*] Author for correspondence: spalvarez@uach.mx

ABSTRACT The cultivation of

pecan nuts is one of the most important economic activities in

Chihuahua, Mexico. In recent years, the price of the walnut has

increased, causing a high profitability of the walnut, this has

motivated several producers to establish new orchards, with high

densities (204 trees per hectare). However, to date there is no reliable

economic information to support that high densities are better than low

ones. For this reason, the objective of this research was to

economically analyze the production of high and low density walnut

orchards. In this study, a quantitative research approach was used. The

required information was collected through 66 surveys (three for each

year of the 11 years analyzed of low and high density plantations)

carried out to walnut producers with high and low density plantations (6

producers per year). From the information from the surveys, the

production costs were determined by considering all the activities

carried out in the high and low density plantations and the income from

harvest sales. The results obtained indicate that production costs in

the first four years were higher at low densities than at high

densities. The yield per nut per walnut from the eighth year was higher

at low densities than at high densities and the yield per hectare was

higher at high densities due to the greater number of walnut trees per

hectare that were planted at high densities. The cost benefit ratio was

higher at low densities than at high densities. To date there is no

information on the production of walnut in low and high density, so this

study is important for farmers, especially in Mexico.

INTRODUCTIONThe walnut cultivation (Carya illinoensis

Koch) is one of the most important in the agricultural region of

Delicias city, Chihuahua. The pecan walnut is native to the southeastern

United States of America and northern Mexico. The cultivation of the

walnut began in Chihuahua State about 400 years ago in the Allende

valley, with Creole trees 1. Nuts are a

perishable product, since they contain a high percentage of oils (70-75

%), 12-15 % of carbohydrates, 9-10 % of proteins, 1.5 % of minerals and 5

% of water 2.

In relation to world walnut production, Mexico produces about 38 % 3

and in Mexico this has increased by around 80 % in the last 30 years

(2003 to 2015), currently reaching around 110 thousand tons 4, from which Chihuahua produces 65 % 5.

COMENUEZ, a Mexican entity of nut producers backed by SAGARPA,

considers that Mexico's nut production could reach 149,685 tons by 2025 6.

In Chihuahua state, walnut plantations predominate with different distances between them (6x6m to 30X30m) 7,8,

however, the high densities favor high yields in first years, but also

increase production costs and a decrease in yield per ha-1 after 10 years of establishment.

The

pecan walnut requires large amounts of light to have a high

photosynthetic efficiency, therefore, shading significantly reduces the

seasonal growth of the shoot and has a negative effect on production,

stability and quality of the walnut 9. In

this regard some author mention that high densities of walnut causes

little light reception due to tree shading since there is intertwining

of branches, reducing the amount of photosynthetically active light

received per area of walnut leaf 10.

Therefore, sugars do not accumulate, growth is affected, causing the

percentage of almonds to decrease. Finally, there is a considerable

reduction in the walnut production per tree, obtaining low yields per ha-1 and a low quality of the walnut 10. Similarly other researchers mention that establishing high walnut densities will produce high yields per ha-1 in the first years of production 11,

which will allow to considerably increase an economic benefit to walnut

producers. However, what has not been reported, perhaps due to

ignorance that in orchards with high densities (204 walnut trees per ha

or more) there will be shading problems after 10 years or more of

establishment, decreasing the yield.

In recent

years the walnut price has increased considerably, causing high

profitability of walnut orchards. This has motivated several producers

to establish new orchards. Some of these are being established at high

densities (204 walnut trees per hectare), that is, at distances between

walnut trees and rows of seven meters. However, producers are faced with

the reality that there is no reliable economic information that allows

them to decide best density of walnut in the new plantations, all this

permitting to obtain the best income in the future. Therefore, the

objective of this study was to analyze some economic aspects in high and

low density walnut orchards.

MATERIALS AND METHODSIn

the present case study a comprehensive qualitative-quantitative

research approach was used, since it refers to systematic and empirical

investigations of the different types of walnut plantations, their

management and productivity. The type of research was conclusive,

descriptive, since they describe the plantation systems used and the

cultivation of alfalfa interspersed between walnut trees (at low

densities).

Walnut trees in Delicias city,

Chihuahua are planted in a wide variety of soils, the most widely used

being clay-sandy loam with a slightly alkaline pH, deep with good

drainage and with a low content of organic matter. The climate in the

region is extreme, semi-arid, with little rainfall, very high

temperatures in the summer (40-41 ℃) and low temperatures in the winter

(-5 to -6 ℃) 12.

The

analytical review technique was used for which the information was

obtained through 66 surveys, of variables such as: initial Investment,

variable costs (application of fertilizers, agrochemicals and foliar,

pruning and irrigation), fixed costs (number of trees planted) and

income from the sale of pecan walnut in production, and from the alfalfa

harvest among the walnut trees. The above from one-year orchards, up to

11 years old, in low and high density.

The plantation frame of 10m x 10m (100 trees ha-1) and high density, the plantation frame of 7m x 7m (204 trees ha-1) was established as low density.

As

an indicator to determine the best plantation economically in the first

11 years after its establishment, the Benefit-Cost (B/C) relationship

was used, this relationship is obtained by dividing the walnut income

per ha between the walnut production cost per ha and investment payback

period for the two production systems studied.

To

determine the production costs of walnut, the cost of the establishment

work the first year, irrigation, fertilization, control of pests,

diseases, elimination of weeds and harvest was considered. For the

above, the methodology proposed by Trusts Instituted in Relation to

Agriculture 13 was used, which is a system

for determining production costs in agricultural and fruit crops.

Alfalfa production cost was determined considering all the tasks carried

out in said crop 14. The information

gathering process was carried out through 66 surveys (three for each

year of the 11 years analyzed of the orchards, low and high density) and

interviews with walnut producers (6 per year). The population

considered in the study was of producers who, in 2018, had an

established orchard with high or low density from one to 11 years of

plantation, in the municipalities of Saucillo, Delicias, Rosales, Meoquí

and Julimes, in Chihuahua State, Mexico.

The

analysis unit for the research was to determine economically which is

the best walnut plantation, for this reason the costs of establishment,

management or labor and income for the production of high and walnut low

densities were analyzed to compare economic income of both systems 13)

to obtain walnut yield per ha. The walnut yield per walnut reported by

each surveyed producer was used, later it was multiplied by the number

of walnut trees according to the plantation framework, to obtain the

yield per ha. The orchards that met the characteristics of both

densities, years of orchard planting and alfalfa establishment as the

second crop among the rows of walnut trees (in low-density plantations)

were selected.

The information collection was

carried out between the months of October-December 2018 through surveys

of walnut producers with orchards established in both densities.

Once

the information was obtained, it was organized, analyzed and the

production and income costs per year were determined. The graphs and

tables required to explain the information were made, using the Excel

program, the investment recovery time was determined in both densities

studied, as well as the Benefit-Cost relationship per year and the one

obtained from costs and income totals at 11 eleven years after its

establishment.

For the statistical analysis, the

data were subjected to a simple variance analysis. The differences

between treatment means were compared using the Tukey test (p <0.05).

The statistical package Statgraphics 5.1 (2001) was used for the

analysis.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONProduction costs per hectare of low and high density walnut treesBased

on the results of the surveys carried out with the producers, as well

as the consultation of information from official sources, on the

establishment and management of the orchards, it was possible to

determine the cost of establishment and management of both production

systems by hectare. (Figure 1).

Costs of establishment and management of high and low density orchards per ha

Source: FCAyF-UACH, 2019

In

each of the years 11 years of study, in the investigation and analysis

of the production establishment of high and low density walnut orchards

In the first year of orchard

establishment, the highest investment cost was in the low-density

plantation plus the cultivation of alfalfa with a cost of $ 69,157.00,

whereas in the high-density orchard a cost of $ 64,764.00 was generated.

In Figure 1 it can be seen that in the first 4 years

the cost of establishment and management in low-density orchards is

higher than the cost and management of high-density orchards. From the

fifth year on, high-density orchards cause the highest management cost

compared to low-density orchards. This result does not coincide with the

one obtained 15 where the high-density

plantation of fruit trees that last less time than walnut to produce,

reached total production in the fourth year and also had the highest

proportion (>80 %) of fruits that were better both in terms of

quality and price. Another result that does not coincide with that

obtained in this research was in plum (Prunus domestica L.) where the establishment costs were 1.9 times higher in the high-density orchard (7,729 € ha -1) than in the low-density one (€ 4,069.3 ha -1), although investment recovered between the second and third year of production 16.

In mango cultivation (Mangifera indica

L.) is unlikely that productivity will increase through the use of high

density plantations without great efforts in plant improvement and

crown management 17. In the specific case

of walnut, pruning is a basic aspect to take into account to increase

yields even more in high-density orchards.

The

higher cost generated in the year of establishment and the following

three years in the low-density walnut orchards is attributed to the

production cost of the intercropped alfalfa crop in the low-density

system, since the total expenditure for the first year ($ 69 157.00),

the cost of the establishment and management of alfalfa corresponds to $

39,533.00, this represents 57 % of the total cost of this low-density

production system. In contrast, the plantation and management of walnut

generates a total cost of $ 29,624.00, which represents 43 % of the

total cost of the production system. In the second, third and fourth

years, alfalfa management cost was again the one that increased the cost

of the low-density system, being 85.7, 75.4 and 71.6 % respectively,

while the management of walnut only represented 14.3, 24.6 and 28.4 % of

the total cost. The increase in the production cost of walnut from the

second year is attributed to the fact that as walnut grows, it requires

greater amounts of inputs such as fertilizers, insecticides and spending

on pruning.

From the fifth year in the

low-density production system, the walnut trees, due to their growth,

occupy more space, causing a lot of shade, which does not allow the

development of another crop among the walnut trees and from this date

the costs were generated only by the management walnut. When making the

comparison of the costs generated by high and low densities, it can be

seen in figure 1 that the high-density orchards in the fifth year

generated a higher cost than those of low densities, in $ 10,086 and

gradually increased in the following years of the fruit tree . In the

tenth year, the cost of producing high densities was $ 20,092 higher

than the cost of producing low-density walnut. This increase in costs

was due to a greater amount of fertilizers, insecticides, pruning,

harvesting and irrigation, due to the greater number of trees.

According

some author the use of high-density plantations in orchards is an

innovative concept to increase productivity without altering the quality

of the fruits 15, even when these

orchards need a greater investment compared to conventional ones, it is

useful to apply the concept because they can provide faster and better

returns on invested funds.

Walnut yield per tree and hectare in low and high walnut densitiesThe

walnut begins its production from the fifth year. Considering that each

producer gives his own management to the garden according to his

knowledge, experience or advisor, it can be said that there is a great

diversity of management that can produce different yields, however,

there are less than 20 walnuts per walnut that produced in its first

year of trial, the number of walnuts increases by the sixth year of age,

but its performance is not significant. From the seventh year according

to the results of the survey, the walnut tree produces an average of

1.5 kg of walnut per tree and increases its yield according to the

management it receives in the orchard, even when the management that is

given depends on the producer.

In low-density orchards (100 walnut trees per ha-1),

it was found that 8-year-old trees have a production of 3.34 kg, on

average, this yield increases to 6.85 kg in the ninth year and to 10 kg

in the tenth year. In high-density orchards until the seventh year there

is no competition for light between walnut trees, therefore, their

yield potential (1.5 kg) is equal to trees established at low densities.

However, after the eighth year, the yield per tree tends to decrease,

in relation to the trees planted at 10 x 10 meters with a yield of 3.33

kg. The yield at nine years is 6 kg, this yield continues to increase on

average to 7.35 kg and 9 kg in the tenth and eleventh year

respectively. These yields of the last 3 years are lower than the yields

that produce walnut trees of the same age at low densities (Figure 2). This lower yield is attributed to what is mentioned by some researchers 10,

that the shading of the leaves causes a lower photosynthetic efficiency

of the leaves, which negatively affects the yield, retention of fruits

and production of flower buds.

Walnut yield per tree and economic analysis of the establishment and production of high and low density walnut orchards

Source: FCAyF-UACH, 2019

In the research, analysis of the production establishment of high and low density walnut orchards

The lower yield obtained from the ninth

year in the high-density orchard is attributed to the fact that from

this date the branches between neighboring walnut trees intertwine

causing less penetration of light to the internal leaves of the walnut.

This low amount of light received by the internal leaves of the walnut

has a negative effect on the tree photosynthesis and consequently its

performance is affected, causing a decrease in it, as reported 10.

When estimating yields per hectare (Figure 3),

it was found that from the seventh year to the eleventh year, the yield

is higher when there is a density of 204 trees (high density).

Walnut yield per hectare and economic analysis of the establishment and production of high and low density walnut orchards

Source: FCAyF-UACH.2019

In the research, analysis of the production establishment of high and low density walnut orchards

The highest performance in high density is

obtained because in this there are more than twice as many walnut trees

as in low density. It is also appreciated that in the seventh and

eighth years the performance at high densities is twice the performance

at low densities. In the eleventh year, a higher yield is obtained at

high densities of 230 kg ha-1 with respect to low densities,

although there are no significant differences. This is attributed to the

fact that from the ninth year the yield per tree at high densities

tends to decrease due to shading effects, which causes less

photosynthesis, decreased emission of flower buds, and walnut fall 10.

In

another investigation, three varieties of almonds were studied in low

and high density and the authors found that the yield per nut tree was

higher in low density, but the yield per ha was higher in high density 18,

this due to the existence of a greater number of trees per hectare.

This result coincides with that of this research where the highest yield

per hectare was also obtained at high densities. This is very important

in the first years of walnut production and one of the producers’

objectives is to obtain higher yields per hectare, in order to achieve

higher income.

In relation to the higher yield

per tree in low densities than in high ones, this is attributed to the

fact that in low densities the tree has a greater space, receives more

light, which causes greater photosynthesis and higher yield. On this

subject, some authors established that growth increases according to

greater accessibility, that is, at low densities 19.

Benefit-cost ratio per hectare in low and high densities of walnutThe

Benefit-Cost Ratio (B/C) is always desired to be greater than one,

being this way it indicates that a greater profit is being generated

than the investment made in the activity that is being practiced. In the

production of walnut with low and high densities, the B / C ratio began

to be analyzed from the first year in the low-density orchards. The

first year, despite the fact that the alfalfa generated an income of $

51,408.00 pesos, the B/C ratio was 0.74, a negative relationship because

the cost of establishing the orchard and the alfalfa was considered.

From the second year onwards, the B/C ratio was greater than one until

the fourth year, while in the high-density orchards, as they did not

generate income, a B/C ratio was not obtained. The good B/C ratio

obtained in the first years in low-density orchards is attributed to the

income generated by the cultivation of alfalfa since in these years the

walnut does not produce. As of the seventh year, which is when the

walnut tree begins to have commercial production, the B/C ratio

generated by income is analyzed. The production in both densities is low

and the management cost is higher than the income obtained, which

generates a B/C ratio of less than one, being much lower from the

seventh to the ninth year in orchards with low density. The higher B/C

ratio obtained in these years in the high-density orchards is attributed

to a higher production of walnut caused by the greater number of trees

per hectare than in the low-density orchards (Table 1).

To date, there is no information on this

subject in walnut, this being the first investigation of this type from

here on the importance of the results that are presented. The relevance

of interspersing the alfalfa with walnut in low densities in the first

four years after the orchard is established is highlighted, since it

allows generating income that helps the maintenance of the walnut

orchard, not being possible in the orchards of high densities, which are

not generate income in these years. However, it is important to note

that, in the first years of walnut production, orchards with high

densities, despite having higher production costs than orchards with low

densities, generate a better B/C ratio. The above, due to the greater

number of walnut trees in high densities. In both walnut densities

studied, the tenth and eleventh year after establishment, a B/C ratio

greater than two is generated. This indicates that in these years and in

the following years, due to the high yield and sale price of the

walnut, the income per hectare will be very beneficial for the

producers, who will be able to recoup the investment in the first years

and obtain profits.

Similar results to those of

this research were reported that in a mango plantation where the B/C

ratio was 1.49 and 2.00 in traditional and high density respectively and

the internal rate of return was higher in high density plantations than

in the traditional 20. A similar result,

but referring to income, was obtained in palm cultivation, where the

analysis indicated that the maximum income could be obtained in high

density compared to conventional 21. In

walnut there is no information on studies of the B/C ratio, this being

the first investigation to compare high and low density plantations.

CONCLUSIONS

The

results obtained indicate the importance of establishing low densities

of walnut intercropped with alfalfa, to obtain income that helps to

cover the costs of managing walnut orchards. Considering the walnut

yield per tree, orchards with low densities (100 walnut trees per ha.)

Are better than those with high densities (204 walnut trees per ha.). In

low-density orchards, each tree from the eighth year produces a higher

yield than trees in high-density orchards.

The

highest overall B/C ratio was achieved in low density compared to high

density plantations. The payback period was first in low-density

orchards (11 years), compared to high-density orchards where there is no

payback during this same period analyzed. In low density orchards in

the eleventh year, a profit of $ 74,590.00 was obtained, while the high

densities had a deficit of $ 45,325.00.