Artículo Original

![]()

0000400004

Incremento del suministro de nutrientes a las plantas en un suelo gley enmendado con vermicompost

[0000-0002-5812-3201] Andy Bernal-Fundora [1] [*]

[0000-0002-0850-9050] Juan A. Cabrera-Rodríguez [1]

[0000-0003-3206-0609] Pedro J. González-Cañizares [1]

[0000-0002-6138-0620] Alberto Hernández-Jiménez [1]

[*] Autor para correspondencia: andy@inca.edu.cu

RESUMEN

La

necesidad de buscar alternativas para mejorar la nutrición de los

cultivos ante la baja fertilidad de los suelos agrícolas y la escasez de

fertilizantes, cobra cada día mayor importancia. Una de estas

alternativas es la aplicación de abonos orgánicos y la inoculación con

hongos micorrízicos arbusculares (HMA). El objetivo del presente trabajo

fue investigar el efecto de las aplicaciones de vermicompost y la

inoculación de un biofertilizante micorrízico sobre el suministro de

nutrientes de un suelo Gley Nodular Ferruginoso para plantas de millo

perla (Panicum italicum L.). Se ejecutaron dos

experimentos en condiciones de mesocosmos en el Instituto Nacional de

Ciencias Agrícolas (INCA), se estudiaron cuatro proporciones de

suelo-vermicompost, con y sin la inoculación micorrízica, en un diseño

completamente aleatorizado con estructura factorial y tres repeticiones.

Se evaluaron la altura, la masa seca de la biomasa aérea y la

concentración y cantidad de nutrientes en las plantas, la frecuencia e

intensidad de la colonización y el número de esporas en el suelo. La

aplicación de vermicompost incrementó la disponibilidad de nutrientes

del suelo y se reflejó en el incremento de la concentración y la

cantidad de nutrientes en las plantas, lo que originó mayor crecimiento y

desarrollo de estas; en presencia del millo perla la aplicación de

vermicompost hizo disminuir la frecuencia e intensidad de la

micorrización, lo que inhibió el efecto de la inoculación con hongos

micorrízicos arbusculares y no se afectó la producción de esporas en el

suelo.

Palabras clave:

vermicompost; micorrizas arbusculares; Glomus; gleysols.

En

los sistemas agrícolas, cuando se ponen en práctica técnicas de

explotación donde no se tomen medidas para la conservación y mejora de

los suelos, paulatinamente se van afectando indicadores de la fertilidad

1,2,

que imposibilitan la obtención de altos rendimientos de los cultivos.

Por eso resulta necesaria la introducción de tecnologías para mejorar su

productividad, mediante un incremento de la disponibilidad de

nutrientes para las plantas, lo que reviste gran importancia en suelos

destinados a la ganadería, donde los niveles de fertilizantes que se

destinan a esta rama no son suficientes para satisfacer la demanda de

nutrientes de los cultivos y el reciclaje de nutrientes resulta

deficiente.

Dentro de las tecnologías para la

recuperación y la conservación de los suelos se encuentra la aplicación

de abonos orgánicos, los cuales tienen efectos positivos sobre el

incremento en el contenido de carbono orgánico (C), incorporación de

elementos minerales e intervienen en la formación de la estructura 3,

tal es el caso del vermicompost, compuesto orgánico que ofrece diversas

cualidades como mejorador del suelo y actúa como fuente de nutrientes

para las plantas 4.

Otras

de las alternativas para un aprovechamiento más eficiente de los

nutrientes por las plantas, es el empleo de los biofertilizantes a base

de hongos micorrízicos arbusculares (HMA), cuyos microorganismos forman

simbiosis con aproximadamente el 90 % de plantas terrestres 5, facilitando la absorción de nutrientes y agua por las mismas, entre otras ventajas 6. El millo perla no queda exento de esta interacción, al ser un cultivo que presenta marcada dependencia micorrízica 7 y, en ocasiones, una elevada colonización micorrízica, incluso al ser inoculados con diferentes especies de HMA 8.

En

estudios previos se ha demostrado como la utilización de especies

eficientes de HMA permite reducir las dosis de fertilizantes minerales o

abonos orgánicos, sin afectar los rendimientos agrícolas de los

cultivos 9-11.

En

una investigación realizada en un suelo Gley Nodular Ferruginoso, que

tuvo como antecedente el cultivo de pastos, se demostró que el uso

combinado del estiércol vacuno, como fuente de abono orgánico y

biofertilizante micorrízico, contribuyó a la mejora de la fertilidad del

suelo, al incremento de la productividad y al valor nutritivo de la

especie poácea forrajera 12.

El

presente trabajo tuvo como objetivo investigar el efecto de las

aplicaciones de vermicompost y la inoculación de un biofertilizante

micorrízico sobre el suministro de nutrientes de un suelo Gley Nodular

Ferruginoso para plantas de millo perla (Panicum italicum L.).

Se

realizaron dos experimentos bajo condiciones de mesocosmos en el área

del invernadero del departamento Biofertilizantes y Nutrición de las

Plantas, del Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Agrícolas (INCA), San José

de las Lajas, Mayabeque, entre los meses de marzo a mayo, durante los

años 2014 y 2015.

El suelo clasificado como Gley Nodular Ferruginoso agrogénico 13,

proveniente del área de la Dirección Municipal de Flora y Fauna del

municipio Boyeros, ocupa el 38,28 % de la superficie total, cuya

extensión es de 897,22 ha y al momento de iniciar la investigación,

llevaba más de 12 años bajo explotación, con pastos y forrajes para la

ganadería, previéndose cambiar su uso mediante el fomento del cultivo de

la moringa (Moringa oleifera); con anterioridad se dedicó al cultivo de la caña de azúcar.

El suelo se caracterizó desde el punto de vista físico y químico 13

y se demostró que poseía un suministro de nutrientes deficiente para

las plantas, destacando la baja disponibilidad fosfórica y potásica y el

bajo contenido de materia orgánica (Tabla 1).

Tabla 1.

Caracterización del

horizonte cultivable del suelo Gley Nodular Ferruginoso agrogénico de la

Dirección Municipal de Flora y Fauna del municipio Boyeros

| Estadígrafos | pH | P2O5 | Ca2+ | Mg2+ | Na+ | K+ | CIB | C |

|---|

| -log [H+] | mg 100 g-1 | cmolckg-1 | g kg-1 |

|---|

| Media | 6,9 | 1,83 | 22,5 | 16 | 0,17 | 0,21 | 38,87 | 12,3 |

| CV (%) | 4,35 | 4,92 | 3,56 | 5,0 | 3,46 | 2,79 | 4,13 | 48,8 |

| IC | ±0,75 | ±0,22 | ±1,99 | ±1,99 | ±0,01 | ±0,01 | ±3,99 | ±1,5 |

pH: potenciometría relación suelo:agua 1:2,5; P2O5: extracción con H2SO4 0,05 mol L-1

relación suelo:solución 1:25 y determinación colorimétrica por el

desarrollo del color azul; Cationes intercambiables: extracción con

acetato de amonio 1 mol L-1 pH 7, determinación del Na y K

por espectrofotometría de llama y del Ca y Mg por volumetría; CIB: suma

de la bases intercambiables; C: carbono orgánico por el método de

Walkley-Black. CV: Coeficiente de Variación; IC: Intervalos de Confianza

Se llenaron bolsas negras de polietileno de 4

kg de capacidad con el suelo, tomando el horizonte cultivable (0-20 cm),

que después de secado al aire, se tamizó por una malla de 5 mm, con el

objetivo de lograr un tamaño de agregado uniforme y se mezcló con el

vermicompost para conformar las diferentes proporciones. El vermicompost

utilizado fue producido en la CCS “Orlando López González”, ubicada en

el municipio La Lisa, La Habana, elaborado a partir de estiércol vacuno y

residuos de cosecha (Tabla 2) y se encontró

en el vermicompost del año 2015, menor contenido de nutrientes, con la

excepción del Mg, mayor humedad, una relación C:N más amplia y un pH más

cercano a la neutralidad.

Tabla 2.

Caracterización en base

seca del vermicompost proveniente de la CCS “Orlando López González”

elaborado a partir de estiércol vacuno y residuos de cosecha

| Años | C | N | P | K | Ca | Mg | Humedad | pH | Relación C:N |

|---|

| (g kg-1) | -log [H+] | adimensional |

|---|

| 2014 | 218,7 | 17,8 | 21,5 | 13,0 | 36,7 | 5,3 | 413 | 7,4 | 12:1 |

| 2015 | 208,2 | 14,8 | 19,9 | 11,9 | 35,3 | 6,2 | 441 | 7,1 | 14:1 |

C: carbono orgánico por el método de Walkley-Black; digestión del vermicompost con H2SO4

+ Se y determinación del N colorimétricamente por Nessler, P por el

desarrollo del color azul, K por espectrofotometría de llama, Ca y Mg

por volumetría; pH: determinación potenciométrica relación

vermicompost:agua 1:2,5

Se utilizó el millo perla (Panicum italicum L.)

como cultivo indicador y se sembraron 10 semillas en cada bolsa; cuando

las plantas alcanzaron entre 10 y 15 cm de altura, se dejaron seis

plantas por bolsa. A partir de la siembra y durante los primeros 15

días, se aplicó un riego diario hasta que las bolsas comenzaran a

drenar; posteriormente se regó cada dos días con igual consideración,

manteniendo las bolsas libres de arvenses, mediante limpieza manual.

Se utilizó el inóculo certificado formulado con la especie Glomus cubense, cepa INCAM 4, producido en el INCA (Y. Rodr. & Dalpé) 14, con una concentración de 28 esporas g-1 de inoculante, el que fue aplicado a las semillas por el método del recubrimiento 15.

Al suelo se le realizó un conteo de esporas residentes en ambos años, al momento del montaje de los experimentos (Tabla 3).

Tabla 3.

Cantidad de esporas en el

suelo Gley Nodular Ferruginoso agrogénico de la Dirección Municipal de

Flora y Fauna del municipio Boyeros al inicio de la investigación

| Año | Cantidad de esporas | Intervalo de Confianza |

|---|

| Esporas 50 g de suelo-1 |

|---|

| 2014 | 68 | 25,21 |

| 2015 | 47 | 28,58 |

| Promedio | 57,5 | 27,00 |

Se estudiaron ocho tratamientos (Tabla 4),

en un diseño completamente aleatorizado, con una estructura factorial y

tres repeticiones; los factores a estudiar fueron las proporciones

suelo/vermicompost con cuatro niveles y la inoculación micorrízica con

dos niveles.

Tabla 4.

Descripción de los

tratamientos utilizados para evaluar el efecto de las aplicaciones de

vermicompost y la inoculación de un biofertilizante micorrízico sobre el

suministro de nutrientes de un suelo Gley Nodular Ferruginoso

agrogénico

| Tratamientos | Proporción suelo-vermicompost (m/m) | Inoculante micorrízico |

|---|

| Suelo | Vermicompost |

|---|

| 1 | 4 | 0 | sin HMA |

| 2 | con HMA |

| 3 | 3 | 1 | sin HMA |

| 4 | con HMA |

| 5 | 5 | 1 | sin HMA |

| 6 | con HMA |

| 7 | 7 | 1 | sin HMA |

| 8 | con HMA |

El suelo provino de la Dirección Municipal de Flora y Fauna del municipio Boyeros

El crecimiento, el rendimiento de biomasa

aérea y la concentración y contenido de N, P y K en ella, se

determinaron a los 50 días después de la emergencia, momento en que las

plantas se encontraban en la fase de grano semiduro con las espigas

amarillas:

Altura de las plantas (cm): mediante el empleo de una cinta métrica, desde la base del tallo hasta el último dewlap visible.

Masa seca de la biomasa aérea (g planta-1): el material cortado se llevó a una estufa de circulación de aire a 70 ºC hasta alcanzar una masa constante.

Concentración de nutrientes (g kg-1): una alícuota del material secado en la estufa se oxidó con una mezcla de H2SO4

concentrado+Se; en el extracto obtenido luego de diluido, se determinó

la concentración de N por el método de Nessler, la de P por el

desarrollo del color azul molibdo fosfórico y la de K por

espectrofotometría de llama.

Contenido de nutrientes (mg planta-1): se calculó a partir de la biomasa seca de la parte aérea y las respectivas concentraciones de cada elemento:

Nutriente (mg planta-1) = [biomasa (mg planta-1) x concentración (g kg-1)/10]

Variables micorrízicas: las raíces de las plantas se trataron según se describe en la literatura 16. La frecuencia y la intensidad de colonización micorrízica se determinó por el método de los interceptos 17. Para la determinación del número de esporas en cada bolsa se empleó el método de extracción 18.

Se

realizó un análisis de varianza bifactorial para las variables

evaluadas. Cuando se encontraron diferencias significativas entre

tratamientos, las medias se compararon según la prueba de Rangos

Múltiples de Duncan (p<0,10). Se determinó el intervalo de confianza

para la media en las variables del análisis químico y en el conteo de

esporas residentes iniciales. Se utilizó el programa Statgraphics

Centurion XV Versión 15.2.14.

En

los dos años de investigación, solo se manifestó el efecto de la

aplicación del vermicompost y no hubo interacción entre los dos factores

investigados en las variables altura de la planta, biomasa aérea seca,

frecuencia e intensidad de la micorrización y concentración y contenido

de nutrientes; mientras que la cantidad de esporas presentes en el suelo

no se afectó con ninguno de los tratamientos.

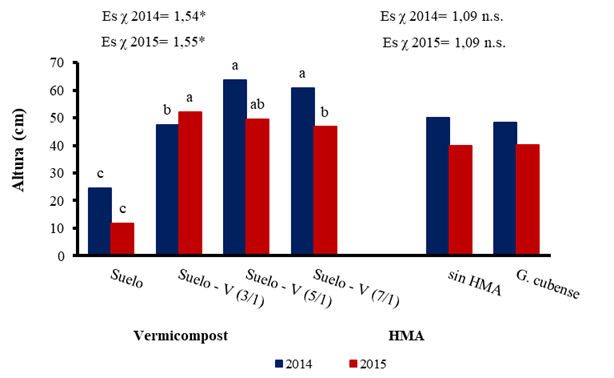

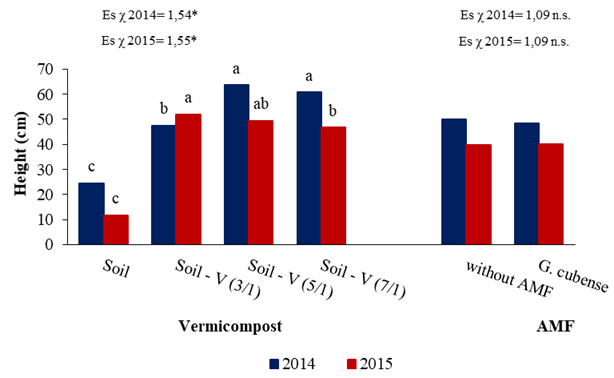

La aplicación de vermicompost incrementó la altura de las plantas (Figura 1)

de manera diferente en cada año; en el año 2014 con las relaciones

suelo/vermicompost 5/1 y 7/1, las plantas alcanzaron mayor altura;

mientras que, en el año 2015, esta manifestación se logró con las

relaciones 3/1 y 5/1 con tendencia a disminuir el efecto en la medida en

que dicha relación se amplió.

V 3/1: relación suelo-vermicompost 3/1, V 5/1: relación suelo-vermicompost 5/1, V 7/1: relación suelo-vermicompost 7/1

Medias con letras iguales para cada factor y año no difieren entre sí según prueba de Duncan (p<0,10)

Figura 1.

Efecto del vermicompost y

de la inoculación con HMA sobre el crecimiento de las plantas de millo

perla. Suelo Gley Nodular Ferruginoso agrogénico

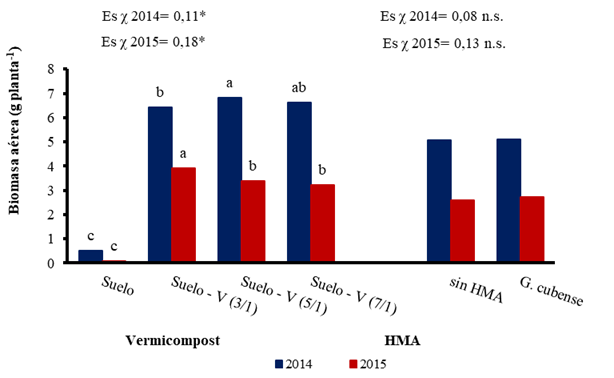

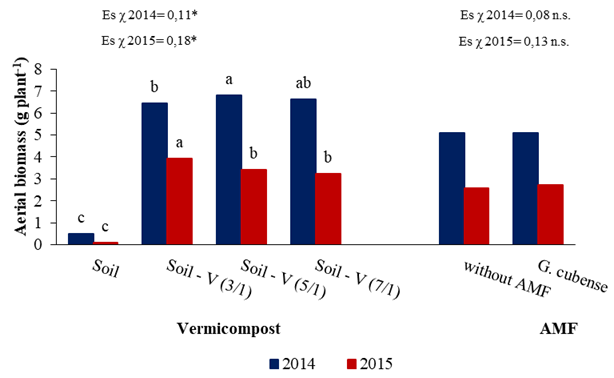

Algo similar se encontró al analizar el rendimiento de masa seca de la biomasa aérea (Figura 2), pero para el año 2015 quedó definida la disminución del rendimiento con las relaciones suelo/vermicompost más amplias.

V 3/1: relación suelo-vermicompost 3/1, V 5/1: relación suelo-vermicompost 5/1, V 7/1: relación suelo-vermicompost 7/1

Medias con letras iguales para cada factor y año no difieren entre sí según prueba de Duncan (p<0,10)

Figura 2.

Efecto del vermicompost y

de la inoculación con HMA sobre la masa seca de la biomasa aérea de las

plantas de millo perla. Suelo Gley Nodular Ferruginoso agrogénico

Los resultados corroboran los alcanzados por

diversos investigadores en otras latitudes y que trabajaron con suelos

diferentes al utilizado en esta investigación. Evaluando el efecto de

diferentes dosis de vermicompost sobre el crecimiento del millo perla,

tanto la altura de las plantas 19,20, así como la acumulación de biomasa 19,

se incrementaron por la aplicación del abono orgánico. También mediante

la aplicación de diferentes tipos de abonos orgánicos, se obtuvo un

incremento de la biomasa aérea del millo perla 21, lo que refleja la respuesta del cultivo ante la aplicación de enmiendas orgánicas.

Se

ha informado que el vermicompost, a partir de las sustancias húmicas,

favorece el desarrollo fenológico de los cultivos al ejercer una acción

bioestimuladora sobre el crecimiento de las plantas, mediante la

incidencia de las fitohormonas producidas por este compuesto orgánico

que estimulan la producción de biomasa 22,23.

Por

otra parte y en condiciones cubanas, con otros cultivos también se ha

podido comprobar el efecto positivo del vermicompost sobre el

crecimiento, de tal manera que trabajando durante dos años en suelo

similar al de esta investigación, se registraron mayores valores de

biomasa en plantas de Panicum maximum y Brachiaria decumbens,

fertilizadas con este abono, efectos que los autores lo atribuyeron a

la mejora de las propiedades físicas, químicas y biológicas del suelo 24.

En

estudios previos se demostró que el vermicompost tiene la

característica de aportar macro y micronutrientes, de incrementar los

contenidos de carbono orgánico y mejorar el pH del suelo 25,26,

lo que incidió en un crecimiento óptimo de las plantas, ya que es un

compuesto rico en elementos minerales, que ya han pasado por un proceso

de descomposición y se encuentran en formas disponibles para las plantas

27.

En

correspondencia con lo mencionado en el párrafo anterior, los resultados

obtenidos referidos a la concentración y el contenido de nutrientes en

las plantas de millo, indicaron que la aplicación del vermicompost

mejoró el suministro de nutrientes para las plantas (Tabla 5, Tabla 6).

Para

el caso del N y en ambos años, tanto en la concentración, como en el

contenido del nutriente en la biomasa aérea seca, todas las proporciones

suelo/vermicompost, tuvieron el mismo efecto y siempre superaron al

suelo solo. El P en al año 2014, se comportó de manera similar al N; sin

embargo, en el año 2015, la mayor concentración y cantidad del

nutriente se encontró en las plantas crecidas en el sustrato con la

relación 3/1, en correspondencia con el comportamiento del rendimiento

de masa seca y se manifestó un incremento en el contenido de este

elemento en las plantas, con inoculación micorrízica. Para el K y en el

año 2014, ambos indicadores de nutrición se manifestaron en mayor

magnitud con la relación 3/1; mientras que, en el año 2015, la

concentración de K no se vio afectada por la aplicación del

vermicompost, pero el contenido fue mayor cuando la relación fue más

estrecha (3/1).

El N fue el nutriente que no

resultó sensible a cambios en función de la relación suelo/vermicompost,

ni de la composición del vermicompost, al menos con las utilizadas en

esta investigación; mientras que el P y el K mostraron cierta

dependencia de ambos. En este sentido, los resultados indicaron que

mientras más estrecha fue la relación, mayor fue la disponibilidad de P y

K para las plantas.

Las diferencias encontradas

entre los años, presumiblemente, se debieron a la composición del

vermicompost. En el utilizado en el año 2015 se encontró menor cantidad

de nutrientes, exceptuando al Mg, mayor humedad y un pH más cercano a la

neutralidad (Tabla 2), requiriéndose mayor cantidad de vermicompost para satisfacer las necesidades de las plantas.

Tabla 5.

Concentración y contenido

de nutrientes del millo perla cosechado a los 50 días después de la

emergencia (fase de grano semiduro). Año 2014

| Tratamiento | N | P | K | N | P | K |

|---|

| suelo/vermicompost | g kg-1 | mg planta-1 |

|---|

| 4/0 | 13,42 b | 1,83 b | 17,98 c | 6,63 b | 0,90 b | 8,98 c |

| 3/1 | 22,77 a | 2,58 a | 37,27 a | 146,92 a | 16,65 a | 240,17 a |

| 5/1 | 22,20 a | 2,52 a | 31,0 b | 151,85 a | 17,12 a | 211,19 b |

| 7/1 | 22,38 a | 2,37 a | 30,22 b | 147,54 a | 15,68 a | 199,81 b |

| Es χ | 2,42* | 0,12* | 1,57* | 16,40* | 0,57* | 10,57* |

| Inoculación micorrízica | |

| - HMA | 19,34 | 2,28 | 28,23 | 108,32 | 12,15 | 158,69 |

| + HMA | 21,04 | 2,38 | 30,01 | 118,15 | 13,03 | 171,38 |

| Es χ | 1,17 n.s. | 0,09 n.s. | 1,11 n.s. | 11,60 n.s. | 0,40 n.s. | 7,47 n.s. |

Suelo: Gley Nodular Ferruginoso agrogénico de la Dirección Municipal de

Flora y Fauna del municipio Boyeros; HMA: inóculo certificado formulado

con la especie Glomus cubense, cepa INCAM 4 producido en el INCA; n.s.:

sin diferencias significativas;

*: diferencias significativas al 10 %

Tabla 6.

Concentración y contenido

de nutrientes del millo perla cosechado a los 50 días después de la

emergencia (fase de grano semiduro). Año 2015

| Tratamiento | N | P | K | N | P | K |

|---|

| suelo/vermicompost | g kg-1 | mg planta-1 |

|---|

| 4/0 | 15,43 b | 1,58 b | 37,87 | 1,48 b | 0,15 c | 3,68 c |

| 3/1 | 22,85 a | 2,82 a | 38,92 | 90,05 a | 11,11 a | 153,02 a |

| 5/1 | 21,98 a | 2,65 a | 36,88 | 75,23 a | 9,03 b | 125,46 b |

| 7/1 | 23,03 a | 2,65 a | 37,55 | 73,67 a | 8,57 b | 120,27 b |

| Es χ | 1,55* | 0,11* | 1,22 n.s. | 7,34* | 0,66* | 7,63* |

| Inoculación micorrízica | |

| - HMA | 19,70 | 2,36 | 37,49 | 53,90 | 6,64 b | 95,28 |

| + HMA | 21,95 | 2,49 | 38,12 | 66,32 | 7,80 a | 105,93 |

| Es χ | 1,09 n.s. | 0,08 n.s. | 0,86 n.s. | 5,19 n.s. | 0,47* | 5,40 n.s. |

Suelo: Gley Nodular Ferruginoso agrogénico de la Dirección Municipal de

Flora y Fauna del municipio Boyeros; HMA: inóculo certificado formulado

con la especie Glomus cubense, cepa INCAM 4 producido en el INCA; NS:

sin diferencias significativas;

*: diferencias significativas al 10 %

El aumento de las concentraciones y los

contenidos de nutrientes en las plantas fertilizadas con humus de

lombriz, puede ser atribuido, tanto al aporte de nutrientes por el abono

orgánico, como al incremento de la disponibilidad de nutrientes del

suelo por efecto de la fertilización orgánica.

En

trabajos realizados previamente, se demostró cómo aplicando diferentes

dosis de vermicompost, se alcanzó una mayor absorción de estos

nutrientes en los órganos aéreos, en el cultivo del millo perla, en

relación con el tratamiento control, lo que influyó en un incremento en

la producción de biomasa seca y rendimiento del cultivo 28.

Igualmente, en estudios realizados en otros cultivos, se comprobó el

incremento en la absorción de N, P y K y el crecimiento de las plantas, a

medida que se aumentaron las dosis de humus de lombriz aplicadas 29.

Este mismo efecto, en cuanto a la absorción de nutriente, se vio

reflejado al aplicar diferentes dosis de ácidos húmicos extraídos del

vermicompost, en plantas de mangostán (Garcinia mangostana. L) 30.

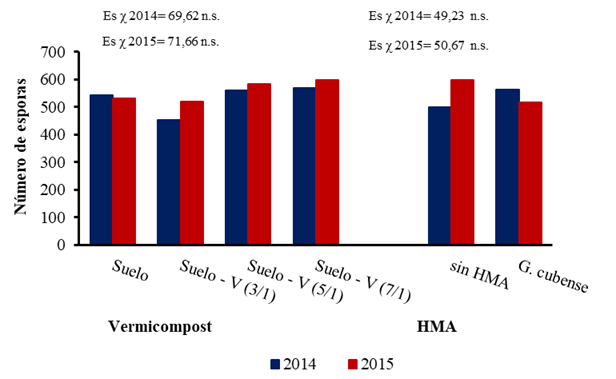

En

los dos años, el vermicompost deprimió la frecuencia e intensidad de la

micorrización y en la medida que la relación suelo/vermicompost se hizo

más amplia, la tendencia encontrada se dirigió hacia el aumento de las

variables evaluadas (Figura 3).

V 3/1: relación suelo-vermicompost 3/1, V 5/1: relación suelo-vermicompost 5/1, V 7/1: relación suelo-vermicompost 7/1

Medias con letras iguales para cada factor y año no difieren entre sí según prueba de Duncan (p<0,10)

Figura 3.

Efecto del vermicompost y

de la inoculación con HMA sobre la frecuencia e intensidad de la

colonización micorrízica en plantas de millo perla. Suelo Gley Nodular

Ferruginoso agrogénico

Lo señalado se puede atribuir a que las

plantas dispusieron de una mayor cantidad de nutrientes, pues en suelos

enriquecidos con abonos orgánicos, se ha comprobado que la

disponibilidad de los nutrientes controla el crecimiento de las

estructuras micorrízicas intra y extrarradicales; de tal modo que,

cuando las plantas han sido fertilizadas suficientemente, la

distribución de dichas estructuras se reduce, ya que la entrega de

nutrientes a la planta hospedera, a través de los HMA, pierde efecto 31.

Estos

resultados coinciden con los obtenidos en otras investigaciones en las

que se aplicaron diferentes fuentes orgánicas y fertilizante mineral en

distintos cultivos y se demostró que cuando la disponibilidad de

nutrientes fue suficiente en el suelo, se garantizó el estado

nutricional de los cultivos y no se favoreció la colonización

micorrízica 32,33.

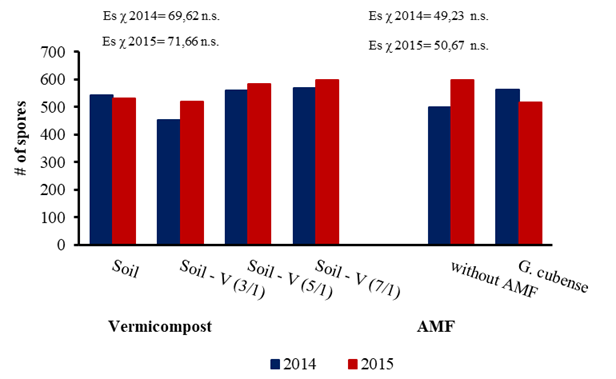

En

cuanto al número de esporas y en los dos años evaluados, los

tratamientos fertilizados con vermicompost no mostraron diferencias, en

relación con los tratamientos con suelo solo, (Figura 4).

V 3/1: relación suelo-vermicompost 3/1, V 5/1: relación suelo-vermicompost 5/1, V 7/1: relación suelo-vermicompost 7/1

Medias con letras iguales para cada factor y año no difieren entre sí según prueba de Duncan (p<0,10)

Figura 4.

Efecto del vermicompost y

de la inoculación con HMA sobre el número de esporas en 50 g de suelo.

Suelo Gley Nodular Ferruginoso agrogénico y millo perla como cultivo

indicador

Al comienzo de ambos experimentos, la cantidad

inicial de esporas de HMA residentes en el suelo fue inferior a 70

esporas por 50 g de suelo (Tabla 3),

mientras que al momento de las evaluaciones, este indicador alcanzó

cifras en el entorno de las 550 esporas en 50 g de suelo (Figura 4);

o sea, 9,5 veces más, cantidades que resultaron similares e incluso

superiores a las observadas en trabajos de campo realizados en el millo

perla, inoculadas con especies micorrízicas del género Glomus34 y otras especies de la familia Poaceae, con un ciclo de crecimiento mayor y cultivadas en condiciones de campo 35.

El

hecho de que el número de esporas obtenido en el tratamiento sin

inocular haya sido similar al observado en el que se aplicó el

inoculante micorrízico, indicó que el millo perla desempeñó un papel

relevante en la reproducción micorrízica, debido a que la arquitectura

radical de este cultivo le confiere una alta capacidad para reproducir

esporas de HMA 36,

favoreciéndose, por tanto, la producción de esporas de HMA residentes y

compitiendo estas con el inóculo aplicado, criterio que coincide con lo

planteado por otros autores, referido a que la simbiosis entre las

plantas y las especies residentes de HMA, en ocasiones, son más

eficientes y competitivas que las establecidas con la especie de

colección inoculada 37. Por

consiguiente y tal como se ha aseverado, el éxito de la inoculación, no

sólo depende de la infectividad y eficiencia de la especie a aplicar,

sino que también está relacionada con la cantidad y tipos de propágulos

residentes en el suelo 38.

La

aplicación de vermicompost incrementa la disponibilidad de nutrientes

del suelo y se refleja en el incremento de la concentración y la

cantidad de nutrientes en las plantas, lo que origina mayor crecimiento y

desarrollo de estas.

La incorporación

del abono orgánico hace que disminuya la frecuencia e intensidad de la

micorrización, inhibiendo el efecto de la inoculación con hongos

micorrízicos arbusculares, sobre las plantas y sin afectar la producción

de esporas en el suelo.

In

agricultural systems, when exploitation techniques are put into

practice where measures are not taken for the conservation and

improvement of soils, fertility indicators are gradually affected 1,2,

which make it impossible to obtain high yields of the crops. That is

why it is necessary to introduce technologies to improve their

productivity, by increasing the availability of nutrients for plants,

which is of great importance in soils destined for livestock, where the

levels of fertilizers that are destined for this branch are not

sufficient to meet the nutrient demand of crops and nutrient recycling

is poor.

Among the technologies for the recovery

and conservation of soils is the application of organic fertilizers. It

has have positive effects on the increase in organic carbon content (C),

incorporation of mineral elements and intervene in the structure

formation 3, such is the case of

vermicompost, an organic compound that offers various qualities as a

soil improver and acts as a source of nutrients for plants 4.

Other

alternatives for a more efficient use of nutrients by plants is the use

of biofertilizers based on arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF), whose

microorganisms form symbiosis with approximately 90 % of terrestrial

plants 5, facilitating the absorption of nutrients and water by them, among other advantages 6. The pearl millet is not exempt from this interaction, because it is a culture that shows marked mycorrhizal dependence 7 and, on occasions, high mycorrhizal colonization, even when inoculated with different AMF species 8.

Previous

studies have shown how the use of efficient AMF species allows reducing

doses of mineral fertilizers or organic fertilizers, without affecting

the agricultural yields of crops 9-11.

In

an investigation carried out in a Gley Nodular Ferruginous soil, which

had pasture cultivation as a precedent, it was shown that the combined

use of cattle manure, as a source of organic fertilizer and mycorrhizal

biofertilizer, contributed to soil fertility improvement, by increased

productivity and nutritional value of forage grass species 12.

The

present work aimed to investigate the effect of vermicompost

applications and the inoculation of a mycorrhizal biofertilizer on the

nutrient supply of a Gley Nodular Ferruginous soil for pearl millet

plants (Panicum italicum L.).

Two

experiments were carried out under mesocosmic conditions in the

greenhouse area of the Biofertilizers and Plant Nutrition department, of

the National Institute of Agricultural Sciences (INCA), San José de las

Lajas, Mayabeque, between months of March to May, during the years 2014

and 2015.

The soil classified as Gley Nodular Ferruginous Agrogenic 13,

from the area of the Municipal Directorate of Flora and Fauna from

Boyeros municipality, occupies 38.28 % of the total surface, whose

extension is 897.22 ha and at the time of starting the research, it had

been under exploitation for more than 12 years, with pastures and

forages for livestock, planning to change its use by promoting the

cultivation of moringa (Moringa oleifera); previously he was dedicated to the cultivation of sugar cane.

The soil was characterized from the physical and chemical point of view 13

and it was shown that it had a deficient supply of nutrients for

plants, highlighting the low phosphoric and potassium availability and

the low content of organic matter (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characterization of the

cultivable horizon of the Gley Nodular Ferruginous Agrogenic soil of

Municipal Directorate of Flora and Fauna from Boyeros municipality

| Parameters | pH | P2O5 | Ca2+ | Mg2+ | Na+ | K+ | CIB | C |

|---|

| -log [H+] | mg 100 g-1 | cmolckg-1 | g kg-1 |

|---|

| Mean | 6.9 | 1.83 | 22.5 | 16 | 0.17 | 0.21 | 38.87 | 12.3 |

| CV (%) | 4.35 | 4.92 | 3.56 | 5.0 | 3.46 | 2.79 | 4.13 | 48.8 |

| IC | ±0.75 | ±0.22 | ±1.99 | ±1.99 | ±0.01 | ±0.01 | ±3.99 | ±1.5 |

pH: soil: water 1:2.5 ratio potentiometry. P2O5: extraction with H2SO4 0.05 mol L-1

soil: 1:25 solution ratio and colorimetric determination by the

development of the blue color. Exchangeable cations: extraction with

ammonium acetate 1 mol L-1 pH 7, determination of Na and K by

flame spectrophotometry and of Ca and Mg by volumetry; CIB: sum of

exchangeable cations; C: organic carbon by the Walkley-Black method. CV:

Coefficient of Variation; CI: Confidence Intervals

Black polyethylene bags of 4 kg capacity were

filled with the soil, taking the cultivable horizon (0-20 cm), which

after air drying, was sieved through a 5 mm mesh, with the objective of

achieving a size of uniform aggregate and mixed with the vermicompost to

make up different proportions. The vermicompost used was produced at

the “Orlando López González” CCS, located in La Lisa municipality,

Havana, made from cow manure and harvest residues (Table 2)

and it was found in the vermicompost of 2015, lower content of

nutrients, with the exception of Mg, higher humidity, a broader C: N

ratio and a pH closer to neutrality.

Table 2.

Characterization on a dry basis of vermicompost from CCS "Orlando López González" made from cow manure and crop residues

| Years | C | N | P | K | Ca | Mg | Humidity | pH | C: N ratio |

|---|

| (g kg-1) | -log [H+] | dimensionless |

|---|

| 2014 | 218.7 | 17.8 | 21.5 | 13.0 | 36.7 | 5.3 | 413 | 7.4 | 12:1 |

| 2015 | 208.2 | 14.8 | 19.9 | 11.9 | 35.3 | 6.2 | 441 | 7.1 | 14:1 |

C: organic carbon by the Walkley-Black method; digestion of vermicompost with H2SO4

+ Se and determination of N colorimetrically by Nessler, P by the

development of the blue color, K by flame spectrophotometry, Ca and Mg

by volumetry; pH: potentiometric determination, vermicompost: water

1:2.5 ratio

Pearl millet (Panicum italicum L.) was

used as an indicator culture and 10 seeds were sown in each bag; when

plants reached between 10 and 15 cm in height, six plants were left per

bag. From sowing and during the first 15 days, a daily irrigation was

applied until the bags began to drain; later it was watered every two

days with equal consideration, keeping the bags free of weeds, by manual

cleaning.

The certified inoculum formulated with the species Glomus cubense, strain INCAM 4, produced at INCA 14, with a concentration of 28 spores g-1 of inoculant, was used, which was applied to the seeds by the coating method 15.

The soil was counted for resident spores in both years, at the time of setting up the experiments (Table 3).

Table 3.

Quantity of spores in the

Gley Nodular Ferruginous agrogenic soil of Municipal Directorate of

Flora and Fauna from Boyeros municipality at the investigation beginning

| Year | Number of spores | Confidence interval |

|---|

| Spores 50 g of soil-1 |

|---|

| 2014 | 68 | 25.21 |

| 2015 | 47 | 28.58 |

| Average | 57.5 | 27.00 |

Eight treatments were studied (Table 4),

in a completely randomized design, with a factorial structure and three

repetitions, the factors to be studied were the soil/vermicompost

ratios with four levels and mycorrhizal inoculation with two levels.

Table 4.

Description of the

treatments used to evaluate the effect of vermicompost applications and

the inoculation of a mycorrhizal biofertilizer on the nutrient supply of

an agrogenic Ferruginous Gley Nodular soil

| Treatments | Soil-vermicompost ratio (m/m) | Mycorrhizal inoculant |

|---|

| Soil | Vermicompost | |

|---|

| 1 | 4 | 0 | with AMF |

| 2 | with AMF |

| 3 | 3 | 1 | without AMF |

| 4 | with AMF |

| 5 | 5 | 1 | without AMF |

| 6 | with AMF |

| 7 | 7 | 1 | without AMF |

| 8 | with AMF |

The soil came from Municipal Directorate of Flora and Fauna from Boyeros municipality

The growth, the aerial biomass yield and the

concentration and content of N, P and K in it, were determined 50 days

after emergence, when the plants were in the semi-hard grain phase with

yellow spikes.

Plant height (cm): using a tape measure, from the stem base to the last visible dewlap.

Dry mass of aerial biomass (g plant-1): the cut material was taken to an air circulation oven at 70 ºC until reaching a constant mass.

Nutrient concentration (g kg-1): an aliquot of the oven-dried material was oxidized with a mixture of concentrated H2SO4

+ Se; in the extract obtained after dilution, N concentration was

determined by the Nessler method, that of P by the development of the

phosphoric molybdo blue color and that of K by flame spectrophotometry.

Nutrient content (mg plant-1): it was calculated from the dry biomass of aerial part and the respective concentrations of each element:

Nutrient (mg plant-1) = [biomass (mg plant-1) x concentration (g kg-1)/10]

Mycorrhizal variables: plant roots were treated as described in the literature 16. The frequency and intensity of mycorrhizal colonization was determined by the intercept method 17. To determine the number of spores in each bag, the extraction method was used 18.

A

bifactorial analysis of variance was performed for variables evaluated

when significant differences were found between treatments, the means

were compared according to Duncan's Multiple Ranges test (p <0.10).

The confidence interval was determined for the mean in the variables of

the chemical analysis and in the count of initial resident spores. The

Statgraphics Centurion XV Version 15.2.14 program was used.

During

the research, only the vermicompost application effect was manifested

and there was no interaction between the two factors investigated in the

following variables: plant height, dry aerial biomass, frequency and

mycorrhization intensity and concentration and content of nutrients;

while the quantity of spores present in soil was not affected with any

of the treatments.

The application of vermicompost increased plant height (Figure 1)

differently in each year. In 2014, with the soil/vermicompost ratios

5/1 and 7/1, plants reached greater height; while, in 2015, this

manifestation was achieved with the 3/1 and 5/1 ratios, with a tendency

to decrease the effect as ratio widened.

V 3/1: soil-vermicompost ratio 3/1, V 5/1: soil-vermicompost ratio 5/1, V 7/1: soil-vermicompost ratio 7/1

Means with the same letters for each factor and year do not differ from each other according to Duncan's test (p <0.10)

Figure 1.

Effect of vermicompost and inoculation with AMF on the growth of pearl millet plants. Agrogenic Ferruginous Nodular Gley Soil

Something similar was found when analyzing the dry mass yield of the aerial biomass (Figure 2), but for the year 2015, the yield decrease with the broader soil/vermicompost ratios was defined.

V 3/1: soil-vermicompost ratio 3/1, V 5/1: soil-vermicompost ratio 5/1, V 7/1: soil-vermicompost ratio 7/1

Means with the same letters for each factor and year do not differ from each other according to Duncan's test (p <0.10)

Figure 2.

Effect of vermicompost and

inoculation with AMF on dry mass of the aerial biomass of pearl millet

plants. Agrogenic Ferruginous Nodular Gley Soil

The results corroborate those achieved by

various researchers in other latitudes and who worked with different

soils from the one used in this research. Evaluating the effect of

different doses of vermicompost on the pearl millet growth, both plant

height 19,20, as well as biomass accumulation 19,

were increased by the organic fertilizer application. Also through the

application of different organic fertilizer types, an increase in the

aerial biomass of pearl millet 21 was obtained, which reflects crop response to organic amendment application.

It

has been reported that vermicompost, from humic substances, favors the

phenological development of crops by exerting a biostimulatory action on

plant growth, through the incidence of phytohormones produced by this

organic compound that stimulate biomass production (22.23).

On

the other hand and in Cuban conditions, with other crops it has also

been possible to verify the positive effect of vermicompost on growth,

in such a way that working for two years in soil similar to that of this

investigation. Higher biomass values were recorded in plants of Panicum maximum and Brachiaria decumbens,

fertilized with this fertilizer, effects that authors attributed to the

improvement of the physical, chemical and biological properties of soil

24.

In

previous studies, it was shown that vermicompost has the characteristic

of providing macro and micronutrients, of increasing organic carbon

content and improving soil pH 25,26,

which influenced optimal plant growth, since it is a compound rich in

mineral elements, which have already undergone a process of

decomposition and they are found in forms available to plants 27.

In

correspondence with what was mentioned in the previous paragraph,

results referring to the concentration and content of nutrients in

millet plants, indicated that vermicompost application improved the

supply of nutrients for plants (Table 5 and (6).

In

the case of N and in both years, both in the concentration and in the

nutrient content in the dry aerial biomass, all the soil/vermicompost

ratios had the same effect and always exceeded the soil alone. The P in

2014, behaved similarly to the N; however, in 2015, the highest

concentration and quantity of the nutrient was found in plants grown in

the substrate with the 3/1 ratio, in correspondence with the behavior of

the dry mass yield and an increase in the content of this element in

plants, with mycorrhizal inoculation. For K and in 2014, both nutrition

indicators were manifested in greater magnitude with the 3/1

relationship; while, in 2015, K concentration was not affected by

vermicompost application, but the content was higher when the ratio was

closer (3/1).

N was the nutrient that was not

sensitive to changes as a function of the soil/vermicompost ratio, nor

of the composition of the vermicompost, at least with those used in this

research; while P and K showed some dependence on both. In this sense,

the results indicated that the closer the relationship, the greater the

availability of P and K for the plants.

N was the

nutrient that was not sensitive to changes as a function of the soil /

vermicompost ratio, nor of the composition of the vermicompost, at least

with those used in this research; while P and K showed some dependence

on both. In this sense, results indicated that the closer the

relationship, the greater the availability of P and K for the plants.

Differences

found between years were presumably due to vermicompost composition. In

the one used in 2015, a lower amount of nutrients was found, except for

Mg, higher humidity and a pH closer to neutrality (Table 2), requiring a greater amount of vermicompost to satisfy the needs of the plants.

Table 5.

Concentration and nutrient content of pearl millet harvested 50 days after emergence (semi-hard grain phase). Year 2014

| Treatment | N | P | K | N | P | K |

|---|

| soil/vermicompost | g kg-1 | mg plant-1 |

|---|

| 4/0 | 13.42 b | 1.83 b | 17.98 c | 6.63 b | 0.90 b | 8.98 c |

| 3/1 | 22.77 a | 2.58 a | 37.27 a | 146.92 a | 16.65 a | 240.17 a |

| 5/1 | 22.20 a | 2.52 a | 31.0 b | 151.85 a | 17.12 a | 211.19 b |

| 7/1 | 22.38 a | 2.37 a | 30.22 b | 147.54 a | 15.68 a | 199.81 b |

| Se χ | 2.42* | 0.12* | 1.57* | 16.40* | 0.57* | 10.57* |

| Mycorrhizal inoculation | |

| - AMF | 19.34 | 2.28 | 28.23 | 108.32 | 12.15 | 158.69 |

| + AMF | 21.04 | 2.38 | 30.01 | 118.15 | 13.03 | 171.38 |

| Se χ | 1.17 n.s. | 0.09 n.s. | 1.11 n.s. | 11.60 n.s. | 0.40 n.s. | 7.47 n.s. |

Soil: Agrogenic Ferruginous Nodular Gley of Municipal Directorate of

Flora and Fauna from Boyeros municipality; AMF: certified inoculum

formulated with the species Glomus cubense, INCAM 4 strain produced at INCA; n.s .: no significant differences;

*: Significant differences at 10%

*: diferencias significativas al 10 %

Table 6.

Concentration and nutrient content of pearl millet harvested 50 days after emergence (semi-hard grain phase). Year 2015

| Treatment | N | P | K | N | P | K |

|---|

| soil/vermicompost | g kg-1 | mg plant-1 |

|---|

| 4/0 | 15.43 b | 1.58 b | 37.87 | 1.48 b | 0.15 c | 3.68 c |

| 3/1 | 22.85 a | 2.82 a | 38.92 | 90.05 a | 11.11 a | 153.02 a |

| 5/1 | 21.98 a | 2.65 a | 36.88 | 75.23 a | 9.03 b | 125.46 b |

| 7/1 | 23.03 a | 2.65 a | 37.55 | 73.67 a | 8.57 b | 120.27 b |

| Se χ | 1.55* | 0.11* | 1.22 n.s. | 7.34* | 0.66* | 7.63* |

| Mycorrhizal inoculation | |

| - AMF | 19.70 | 2.36 | 37.49 | 53.90 | 6.64 b | 95.28 |

| + AMF | 21.95 | 2.49 | 38.12 | 66.32 | 7.80 a | 105.93 |

| Se χ | 1.09 n.s. | 0.08 n.s. | 0.86 n.s. | 5.19 n.s. | 0.47* | 5.40 n.s. |

Soil: Agrogenic Ferruginous Nodular Gley of Municipal Directorate of

Flora and Fauna from Boyeros municipality; AMF: certified inoculum

formulated with the species Glomus cubense, INCAM 4 strain produced at

INCA; NS: no significant differences;

*: significant differences at 10%

The increase in concentrations and nutrient

contents in plants fertilized with earthworm humus can be attributed

both to the contribution of nutrients by organic fertilizer and to the

increase in the availability of nutrients from the soil due to the

effect of organic fertilization.

In previous

works, it was demonstrated how by applying different doses of

vermicompost, a greater absorption of these nutrients was achieved in

the aerial organs, in the pearl millet culture, in relation to the

control treatment, which influenced an increase in production dry

biomass and crop yield 28.

Likewise, in studies carried out in other crops, the increase in the

absorption of N, P and K and the growth of plants was verified, as the

doses of earthworm humus applied were increased 29.

This same effect, in terms of nutrient absorption, was reflected when

applying different doses of humic acids extracted from vermicompost, in

mangosteen plants (Garcinia mangostana. L) 30.

In

the two years, vermicompost depressed the frequency and intensity of

mycorrhization and as the soil/vermicompost relationship became broader,

the trend found was directed towards an increase in the variables

evaluated (Figure 3).

V 3/1: soil-vermicompost ratio 3/1, V 5/1: soil-vermicompost ratio 5/1, V 7/1: soil-vermicompost ratio 7/1

Means with the same letters for each factor and year do not differ from each other according to Duncan's test (p <0.10)

Figure 3.

Effect of vermicompost and

AMF inoculation on the frequency and intensity of mycorrhizal

colonization in pearl millet plants. Agrogenic Ferruginous Nodular Gley

Soil

The aforementioned can be attributed to the

fact that plants had a greater quantity of nutrients, since in soils

enriched with organic fertilizers. It has been proven that nutrient

availability controls the growth of intra- and extra-radical mycorrhizal

structures; in such a way that, when plants have been sufficiently

fertilized, the distribution of the structures is reduced, since the

delivery of nutrients to the host plant, through AMF, loses effect 31.

These

results coincide with those obtained in other investigations in which

different organic sources and mineral fertilizer were applied in

different crops and it was shown that when the availability of nutrients

was sufficient in the soil, the nutritional status of crops was

guaranteed and it was not enhanced mycorrhizal colonization 32,33.

Regarding

the number of spores and in years evaluated, the treatments fertilized

with vermicompost did not show differences, in relation to the

treatments with soil alone, (Figure 4).

V 3/1: soil-vermicompost ratio 3/1, V 5/1: soil-vermicompost ratio 5/1, V 7/1: soil-vermicompost ratio 7/1

Means with the same letters for each factor and year do not differ from each other according to Duncan's test (p <0.10)

Figure 4.

Effect of vermicompost and

AMF inoculation on the number of spores in 50 g of soil. Agrogenic

Ferruginous Gley Nodular Soil and pearl millet as indicator culture

At the beginning of both experiments, the

initial quantity of AMF spores resident in the soil was less than 70

spores per 50 g of soil (Table 3), while at evaluation time, this indicator reached figures around 550 spores in 50 g of soil (Figure 4);

that is, 9.5 times more. Those amounts were similar and even higher

than those observed in fieldwork carried out on the pearl millet,

inoculated with mycorrhizal species of the genus Glomus34 and other species of the Poaceae family, with a cycle of greater growth and cultivated in field conditions 35.

The

fact that the number of spores obtained in the treatment without

inoculation was similar to that observed in which the mycorrhizal

inoculant was applied, indicated that the pearl millet played a relevant

role in mycorrhizal reproduction, due to the fact that the radical

architecture of this culture gives it a high capacity to reproduce AMF

spores 36. It enhances, the

production of resident AMF spores and competing these with the inoculum

applied, a criterion that coincides with that proposed by other authors,

referring to the fact that the symbiosis between plants and resident

AMF species, they are sometimes more efficient and competitive than

those established with the inoculated collection species 37.

Consequently,

and as has been asserted, the success of the inoculation not only

depends on the infectivity and efficiency of the species to be applied,

but it is also related to the amount and types of propagules resident in

the soil 38.

The

application of vermicompost increases the availability of nutrients in

the soil and is reflected in the increase in the concentration and

quantity of nutrients in the plants, which causes greater growth and

development of these.

The incorporation

of organic fertilizer reduces the frequency and intensity of

mycorrhization, inhibiting the effect of inoculation with arbuscular

mycorrhizal fungi on plants and without affecting the production of

spores in the soil.