Artículo original

![]()

0000800008

Influencia de la densidad de población en el cultivo de maíz (Zea mays L.)

[0000-0002-6325-1005] Yaisys Blanco-Valdes [1] [*]

[0000-0002-4923-812X] Deborah González-Viera [1]

[*] Autor para correspondencia: yblanco@inca.edu.cu

RESUMEN

Con

el objetivo de determinar el efecto de la densidad de población sobre

el rendimiento del cultivo del híbrido HST-3235 de maíz (Zea mays

L.), se condujo un estudio en áreas experimentales del Instituto

Nacional de Ciencias Agrícolas (INCA). El experimento se realizó sobre

un suelo Ferralítico Rojo Lixiviado típico, eútrico, bajo un diseño

experimental de bloques al azar con tres tratamientos y tres réplicas.

Las densidades de población fueron de 44 444, 74 074 y 88 888 plantas ha-1. La densidad de 88 888 plantas ha-1

presentó el mayor rendimiento. Para la emergencia de las plántulas de

maíz influyó la profundidad de siembra, por lo que no todas emergieron

de forma uniforme.

Palabras clave:

densidad de plantación; granos; híbridos; mazorca de maíz.

La

producción de materia seca de un cultivo está directamente relacionada

con el aprovechamiento de la radiación solar incidente. Además, para

alcanzar los máximos rendimientos en situaciones sin limitaciones

ambientales importantes, los cultivos deben aprovechar en su totalidad

la radiación solar disponible durante los momentos críticos de

determinación de rendimientos 1.

En

el cultivo de maíz, la densidad de plantas tiene importantes efectos en

la aparición de materia seca entre las estructuras vegetales y

reproductivas. El rendimiento de este cultivo presenta escasa

estabilidad frente a variaciones en la densidad de plantas y es

sumamente sensible a la disminución en la cantidad de recursos por la

planta, principalmente, en el periodo de la floración 2,3.

En

consecuencia, el ajuste de la densidad de plantas resulta especialmente

crítico en este cultivo. La elección de la densidad es un factor

importante de producción del cultivo de maíz al alcance del agricultor.

Por tal motivo, resulta deseable, por parte de los agrónomos, definir

las relaciones entre la cantidad de plantas logradas por unidad de

superficie en un cultivo y su rendimiento, para distintas situaciones de

oferta ambiental 4.

La

densidad de población, es considerada como el factor controlable más

importante para obtener mayores rendimientos en los cultivos. En el maíz

ejerce alta influencia sobre el rendimiento de grano y las

características agronómicas, pues el rendimiento de grano se incrementa

con la densidad de población, hasta llegar a un punto máximo y disminuye

cuando la densidad se incrementa más allá de este punto 5.

La densidad de población es uno de los factores que frecuentemente

modifica el productor para incrementar el rendimiento de grano, pero no

siempre establece la densidad adecuada. Si el productor utiliza una

densidad de población mayor que la óptima, incrementa la competencia por

luz, agua y nutrimentos, lo que ocasiona reducción en el volumen

radical, número de mazorcas, cantidad y la calidad del grano por planta e

incrementa la frecuencia de pudriciones de raíz y tallo, lo que

propicia el acame 6. Por el contrario, las densidades de población bajas, provocan problemas con arvenses o de desperdicio de suelo 7.

La

relación entre la producción de grano y la densidad de población es

compleja, debido a que la mejor respuesta en rendimiento de grano varía

de acuerdo a la condición del suelo, el clima, las prácticas culturales y

el genotipo 5. El Centro Internacional de Mejoramiento de Maíz y Trigo (CIMMYT) sugiere densidades óptimas de siembra de 65 000 plantas ha-1, para genotipos tropicales de maíz que tengan una altura de la planta superior a los 2,4 m 8.

Trabajos realizados sobre densidades de población en híbridos de maíz

bajo temporal, en el trópico húmedo, demostraron que al aumentar la

densidad de 50 000 a 62 500 planta ha-1, obtuvieron el mayor rendimiento de grano, pues se incrementó en 0,30 t ha

-1 (9)

. También se reportó que el rendimiento aumentó 0,6 t ha-1, al incrementar la densidad de población de 60000 a 70 000 plantas ha

-1 (10)

. Varios estudios indicaron que el maíz difirió en su respuesta a

la densidad de población en función del genotipo y de las condiciones

ambientales 11.

Por

lo anterior, el objetivo del presente estudio fue determinar el efecto

de la densidad de población sobre el rendimiento del cultivo del maíz,

lo cual permitirá identificar la densidad para obtener el mayor

rendimiento de grano.

La

investigación se desarrolló en el periodo poco lluvioso (diciembre)

entre los años 2017 y 2018, en áreas experimentales del Instituto

Nacional de Ciencias Agrícolas (INCA), ubicadas en San José de las

Lajas, provincia Mayabeque, km 3½ de la carretera a Jamaica, teniendo su

centro en los 22º59'40,79" de latitud Norte y 82º8'21,88" de longitud

Oeste 12, a una altitud de 138 m s.n.m.

Las

características climáticas del agroecosistema donde se desarrollaron

los experimentos pertenecen a la antigua clima-región Habana, la cual se

extiende al noreste de la provincia de La Habana y se caracteriza por

presentar un período poco lluvioso de corta duración, que se extiende

desde el mes de noviembre hasta el mes de marzo, sin llegar a producir

una típica sequía ecológica 13.

La temperatura media mensual de los dos años que abarcó la investigación, osciló entre 17 y 27,4 oC

en correspondencia con los meses menos calurosos y menos lluviosos

(noviembre-abril) y los más calurosos y lluviosos (mayo-octubre),

respectivamente, mientras que las precipitaciones mensuales variaron

desde 3,4 mm en la etapa menos lluviosa a 423,0 mm en la más lluviosa.

En esta variable hay que destacar que los menores acumulados ocurrieron

en los meses de diciembre a marzo, período durante el cual se desarrolló

el cultivo del maíz. La humedad relativa se comportó entre un 70 % a 86

%, durante la etapa experimental, siendo superior en el período

lluvioso.

El suelo predominante del área de

estudio es Ferralítico Rojo Lixiviado típico eútrico, caracterizado por

una fertilidad de media a alta 14.

Algunas características químicas del suelo, se muestran en la Tabla 1.

Tabla 1.

Algunas características químicas del suelo

| Profundidad (cm) | pH (H2O) | MO (%) | P (mg kg1) | K+Ca2+Mg2+ | (cmolc kg-1) | |

|---|

| 0-20 | 6,4 | 2,11 | 234 | 0,52 | 9,93 | 1,80 |

Este suelo es medianamente profundo con un pH

ligeramente ácido, presenta un bajo porcentaje de materia orgánica, el

contenido de fósforo y calcio en el suelo es alto; sin embargo, el

potasio y el magnesio son bajos, lo cual indica que para lograr

producciones óptimas será necesario suplirlas con aplicaciones

adicionales de nutrientes al suelo, según necesidades de los cultivos.

La fertilización se realizó con nitrógeno al momento de la siembra a razón de 50 kg ha-1 y 100 kg ha-1

de potasio, utilizando como portadores urea y cloruro de potasio,

respectivamente, no se fertilizó con fósforo pues el contenido en el

suelo era alto (Tabla 1).

La preparación del suelo y la siembra se realizó según lo recomendado en la Guía Técnica para el cultivo del maíz 15, estableciéndose el híbrido HST-3235 a tres distancias de plantación (Tabla 2).

Tabla 2.

Identificación y descripción de los tratamientos

| Tratamientos | Densidades de siembra |

|---|

| 1 | 0,90 x 0,30 m con 2 granos por nido, Testigo de producción |

| 2 | 0,90 x 0,25 m con 1 grano por nido |

| 3 | 0,90 x 0,25 m con 2 granos por nido |

La superficie de la unidad experimental fue

de 6 x 5,4 m, separadas a 1 m de ancho. El manejo de las arvenses

(deshierbes) se realizó de forma mecánica y manual semanalmente. Los

experimentos fueron conducidos bajo un diseño de bloques al azar con

tres réplicas y tres tratamientos.

El riego fue

por aspersión con espaciamiento de 12 x 12 m. El régimen de riego

(explotación) fue con intervalo constante y norma variable, en la Tabla 3 se muestran algunos datos del riego.

Tabla 3.

Norma de riego aplicada según el espaciamiento a 3,0 BAR

| No. de riego | Fecha | Tiempo de riego (horas) | Norma aplicada según el espaciamiento a 3,0 BAR |

|---|

| mm | m3/ha |

|---|

| 1 | 1ra decena/diciembre/2018 | 1 | 15 | 146,5 |

| 2 | 2da decena/diciembre /2018 | 2 | 29 | 293 |

| 3 | 3ra decena/diciembre /2018 | 2 | 29 | 293 |

| 4 | 1ra decena/enero/2019 | 2 | 29 | 293 |

| 5 | 2da decena/enero/2019 | 2.5 | 37 | 366,2 |

| 6 | 3ra decena/enero/2019 | 2.5 | 37 | 366,2 |

| 7 | 1ra decena/febrero/2019 | 2.5 | 37 | 366,2 |

Nota: 1 mm de la capa de agua equivale a 10 m3 ha-1

La Metodología utilizada para determinar el

número de plantas por superficie, fue a partir de la distancia promedio

entre las plantas (narigón) en varios puntos del campo para garantizar

representatividad, se multiplicó por la distancia de camellón. Esto

proporciona la superficie ocupada por cada planta, teniendo la

superficie total del campo, esta se divide entre la usada por una

planta, dando de esta forma, la cantidad de plantas en la superficie 16.

No. de plantas = Sn / n x c

donde:

Sn: superficie neta (metros)

n: distancia de narigón (metros)

c: distancia de camellón (metros)

La variable evaluada fue el rendimiento (t ha-1).

También se determinó la profundidad de siembra (cm) para conocer como

influía la emergencia de las plantas en esta variable, en diferentes

puntos del experimento, se removió el suelo hasta que la planta

estuviera descubierta y se midió con una regla milimetrada desde el

mesocotilo hasta la última hoja y la altura de la planta (m), se midió

desde la base del tallo hasta el último nudo donde se inserta la flor,

se tuvo el promedio para cada parcela, a los 70 días después de la

emergencia se tomaron 30 plantas al azar, dentro de la parcela útil. Los

datos obtenidos se procesaron y analizaron estadísticamente, utilizando

el análisis de varianza de clasificación doble y, en los casos

necesarios, se realizó la prueba de rangos múltiples de Duncan al 5 % de

probabilidad.

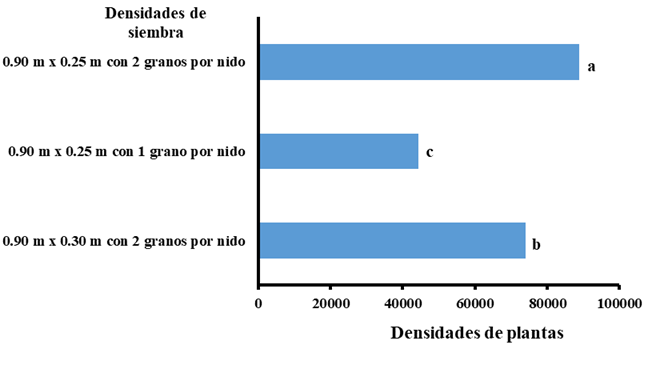

Comparación de las densidades de siembra

Se realizó un conteo de plantas totales a cosecha, para determinar la densidad de plantas (Figura 1).

El análisis individual por densidad de siembra tuvo diferencias

significativas con respecto a la densidad de plantas. El mejor

tratamiento fue el de la densidad de siembra 0,90 x 0,25 m con dos

granos por nido, con una densidad de plantas de 88 888, siendo

significativamente diferente a las otras dos densidades de 74 074 y 44

444 plantas ha-1.

Figura 1.

Densidades de plantas en función de las densidades de siembra

La relación entre la producción de grano y

la densidad de población es compleja, ya que la mejor respuesta en

rendimiento de grano varía de acuerdo a la condición de suelo, clima,

prácticas culturales y genotipo 5. El Centro Internacional de Mejoramiento de Maíz y Trigo (CIMMYT) sugiere densidades óptimas de siembra de 65 000 plantas ha-1 para genotipos tropicales de maíz que tengan una altura de la planta superior a los 2,4 m 8.

Trabajos realizados sobre densidades de población en híbridos de maíz,

bajo temporal en el trópico húmedo, demostraron que al aumentar la

densidad de 50 000 a 62 500 plantas ha-1se obtuvo un incremento del rendimiento de grano de 0,30 t ha

-1 (9)

. También se ha reportado que el rendimiento aumentó 0,6 t ha-1, al incrementar la densidad de población de 60000 a 70 000 plantas ha

-1 (10)

. Varios estudios reportan diferencias en la respuesta del maíz a

la densidad de población, en función del genotipo y de las condiciones

ambientales 11, resultados que coinciden con los obtenidos.

Rendimientos de los cultivos del maíz (mazorca)

En la Tabla 4

se muestra el rendimiento del maíz en mazorcas tiernas y en granos. El

consumo de maíz en Cuba, generalmente se hace cuando los granos están en

su estado “tierno”, esta modalidad tiene la ventaja de liberar la

superficie antes de culminar el ciclo del cultivo y permite adelantar la

entrada del nuevo cultivo y, con ello, se eleva el coeficiente de

rotación 17.

Tabla 4.

Rendimiento del maíz tierno (mazorcas) y granos (t ha-1

)

| Tratamientos | Rendimiento del maíz tierno (t ha-1 ) |

|---|

| mazorcas | granos |

|---|

| 0,90 x 0,30 m con 2 granos por nido | 9,619b | 3,237b |

| 0,90 x 0,25 m con 1 grano por nido | 7,223c | 3,112c |

| 0,90 x 0,25 m con 2 granos por nido | 11,800 a | 4,971 a |

Las medias seguidas de letras distintas, en la columna, para cada

variable en análisis conjunto, difieren entre sí con el nivel de

significación de 0,05 de probabilidad, según prueba de Duncan (1955).

*** P˂0,001

Con respecto a las distancias de siembra

0,90 x 0,30 m con 2 granos por nido y 0,90 x 0,25 m con 2 granos por

nido, la respuesta estuvo en correspondencia con lo señalado por lo

planteado 18, al indicar como producciones exitosas de mazorcas tiernas, por encima de 9 t ha-1; no siendo asi para 0,90 x 0,25 m con 1 grano por nido.

La

producción de granos verdes sin brácteas (49 %) y tusa (34 %) se

corresponde con los resultados esperados al haber coincidencia con la

producción de mazorcas; además, coincidió con el rango de la producción

que normalmente se obtiene en Cuba, para el indicador de producción de

granos verdes 19,20, que se considera buena si la producción de granos está por encima de 3,5 t ha-1;

el rendimiento obtenido estuvo en correspondencia con los alcanzados en

otras investigaciones, donde se utilizó un híbrido de maíz con

diferentes densidades de siembra 15.

El rendimiento de grano osciló entre 3, 112 y 4,971 t ha-1.

El mayor rendimiento de grano y mazorcas se obtuvo con 0,90 x 0,25 m

con 2 granos, al comparar con el testigo de producción más utilizado en

las producciones; mientras que el menor rendimiento se presentó con la

densidad 0,90 x 0,25 m con 1 grano por nido.

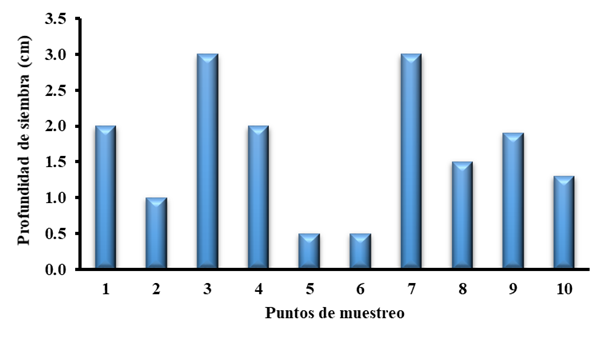

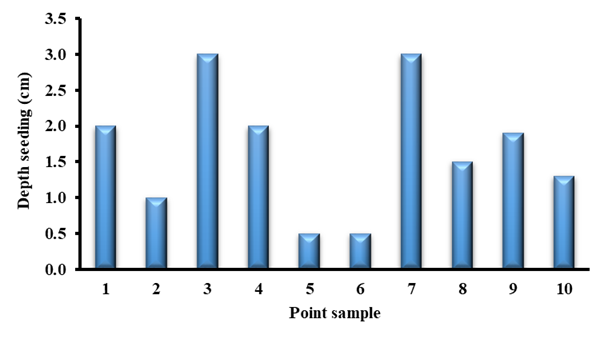

Por

otra parte, la altura de la mazorca varió entre 0,92 y 1,23 m, lo que

pudo estar en correspondencia con la profundidad de siembra que no fue

uniforme (Figura 2), lo que provocó que todas las plántulas no emergieran al mismo tiempo como se muestra en la Figura 3.

Los

tratamientos de mayores densidades de población fueron los que

mostraron la mayor altura de la mazorca superior (AMS), este indicador

muestra gran importancia, ya que la altura de las mazorcas puede

dificultar la labor de cosecha manual si esta es muy elevada; además, es

más propenso al acame, debido al peso que soporta el tallo 21;

por tanto, en este caso es bueno seleccionar los tratamientos de menor

altura de la mazorca superior o que tenga una buena relación con la

altura de la planta. Al relacionar la altura de la mazorca superior con

la altura de la planta, se puede plantear que la altura de la planta es

un parámetro que depende, en gran medida, de factores externos del

medio; en este sentido, los tratamientos con mayor altura de la planta

tienen las menores distancias entre estas y el mayor número de plantas

por nido, lo que aumenta la densidad y provoca un mayor crecimiento 22.

Vale

destacar que en esta variable no se encontraron diferencias

significativas entre los tratamientos; el resultado evidencia que en

bajas densidades de siembra, las plantas de maíz tuvieron menos

competencia por agua y nutrientes y viceversa, así crecen en busca de la

luz solar, de esta manera iguala en la altura a las plantas que se

sembraron en bajas densidades.

Con la densidad 88 888 plantas ha-1,

se alcanzó la mayor altura, relacionado a esto, otros autores mencionan

que la altura de la planta es un parámetro que depende, en mayor

medida, de factores externos del medio 22;

en este sentido, los tratamientos con mayor altura de la planta tienen

las menores distancias entre plantas y el mayor número de plantas por

nido, lo que hace que se aumente la densidad y esto provoca un mayor

crecimiento.

Figura 2.

Profundidad de siembra en diferentes puntos del experimento (cm)

La cantidad de agua que recibió el cultivo

durante su desarrollo fue de 550 mm, como resultado de la precipitación

pluvial registrada durante el desarrollo del cultivo (337 mm) y el riego

aplicado (213 mm), que se encuentra dentro del intervalo adecuado (500 a

1 000 mm) para el cultivo de maíz en el trópico húmedo 23. Bajo las condiciones del presente estudio, el incremento en densidad de 44 444 a 88 888 plantas ha-1

aumentó el rendimiento de granos en un 50 %. Este incremento fue

similar al encontrado en otros estudios, en los cuales se observaron

aumentos del rendimiento de grano en densidades superiores a 50 000

plantas ha

-1 (10,24)

.

Figura 3.

Influencia de la profundidad de siembra en la altura de las plántulas después de la emergencia

A pesar de que la altura de la planta y la altura de la mazorca, resultaron superiores a los mencionados en otros estudios 25; el aumento de la densidad de población, resultó similar a la reportada por otros autores 26,27.

Se

obtuvo un aumento del rendimiento a mayor densidad de población, por lo

que se sugiere tener en cuenta, para otros estudios, la densidad de

población 88 888 plantas ha-1 para el híbrido HST-3235; de aquí se infiere, que puede soportar mayores densidades de población.

Los

rendimientos más altos del híbrido HST-3235 se obtienen con un marco de

plantación de 0,90 x 0,25 m con 2 granos por nido y una densidad de

siembra que oscile entre 74-88 mil plantas ha-1.

La profundidad de siembra influyó en la emergencia de las plántulas de maíz, por lo que no todas emergieron de forma uniforme.

Original article

Influence of population density on maize crop (Zea mays L.)

[0000-0002-6325-1005] Yaisys Blanco-Valdes [1] [*]

[0000-0002-4923-812X] Deborah González-Viera [1]

[1] Instituto

Nacional de Ciencias Agrícolas (INCA), carretera San José-Tapaste, km

3½, Gaveta Postal 1, San José de las Lajas, Mayabeque, Cuba. CP 32 700

[*] Author for correspondence: yblanco@inca.edu.cu

ABSTRACT

In

order to determine the effect of population density on the hybrid

HST-3235 maize (Zea mays L.) crop yield, a study in experimental areas

of the National Institute of Agricultural Sciences (INCA) was conducted.

The experiment was performed on a typical Eutric Leached Red

Ferrallitic soil, under a randomized block experimental design with

three treatments and three replications. Population densities were

44,444, 74,074 and 88,888 plants ha-1. The density of 88 888 plants ha-1 presented the highest yield. Planting depth influenced the emergence of corn seedlings, so not all of them emerged uniformly.

Key words:

planting density; grains; hybrids; cob corn.

The

dry matter production of a crop is directly related to the use of

incident solar radiation. Furthermore, to achieve maximum yields in

situations without significant environmental limitations, crops must

take full advantage of the available solar radiation during critical

moments of yield determination 1.

In

corn cultivation, plant density has important effects on dry matter

appearance of between plant and reproductive structures. The yield of

this crop shows little stability against variations in plant density and

it is highly sensitive to the decrease in the amount of resources per

plant, mainly in the flowering period 2,3.

Consequently,

adjusting the plant density is especially critical in this crop. The

choice of density is an important factor of corn crop production within

the reach of the farmer. For this reason, it is desirable for

agronomists to define the relationships between the number of plants

achieved per unit area in a crop and their yield, for different

situations of environmental supply 4.

Population

density is considered the most important controllable factor to obtain

higher crop yields. In corn, it exerts a high influence on grain yield

and agronomic characteristics, since grain yield increases with

population density, until it reaches a maximum point and decreases when

density increases beyond this point 5.

Population density is one of the factors that the producer frequently

modifies to increase grain yield, but it does not always establish the

adequate density. If the producer uses a population density greater than

the optimal one, it increases the competition for light, water and

nutrients, which causes a reduction in root volume, cob number, quantity

and quality of the grain per plant and increases the frequency of root

and stem rotting, which favors lodging 6. On the contrary, low population densities cause problems with weeds or soil waste 7.

The

relationship between grain production and population density is

complex, because the best response in grain yield varies according to

soil condition, climate, cultural practices, and genotype 5.

The International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT, according

its acronyms in Spanish) suggests optimal stocking densities of 65,000

plants ha-1, for tropical maize genotypes with a plant height greater than 2.4 m 8.

Work carried out on population densities in seasonal low corn hybrids,

in humid tropics, showed that when increasing the density from 50,000 to

62,500 plant ha-1, they obtained the highest grain yield, since it increased by 0.30 t ha-1 (9. It was also reported that the yield increased 0.6 t ha-1, when increasing the population density from 60,000 to 70,000 plants ha-1 (10.

Several studies indicated that maize differed in its response to

population density as a function of genotype and environmental

conditions 11.

Therefore,

the objective of this study was to determine the effect of population

density on the yield of the corn crop, which will allow identifying the

density to obtain the highest grain yield.

The

research was developed in dry period (December) between 2017 and 2018,

in experimental areas of the National Institute of Agricultural Sciences

(INCA), located in San José de las Lajas, Mayabeque province, km 3½ of

the road to Jamaica. It has its center at 22º59'40.79 "North latitude

and 82º8'21.88" West longitude 12, at an altitude of 138 m a.s.l.

The

climatic characteristics of the agroecosystem where the experiments

were carried out belong to the old Havana climate-region, which extends

to the northeast of the province of Havana and is characterized by

presenting a short rainy period, which extends from the month from

November to March, without actually producing a typical ecological

drought 13.

The mean monthly temperature of the two years covered by the research ranged between 17 and 27.4 ºC

in correspondence with the less hot and less rainy months

(November-April) and the hottest and rainiest (May-October),

respectively while monthly rainfall varied from 3.4 mm in the least

rainy stage to 423.0 mm in the wettest. In this variable, it should be

noted that the accumulated minors occurred in the months of December to

March, the period during which the cultivation of corn was developed.

Relative humidity behaved between 70 to 86 %, during the experimental

stage, being higher in the rainy period.

The predominant soil in the study area is typical eutric leached Red Ferrallitic, characterized by a medium to high fertility 14.

Some chemical characteristics of the soil are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Some chemical characteristics of the soil

| Depth (cm) | pH (H2O) | OM (%) | P (mg kg1) | K+Ca2+Mg2+ | (cmolc kg-1) | |

|---|

| 0-20 | 6.4 | 2.11 | 234 | 0.52 | 9.93 | 1.80 |

This soil is moderately deep with a slightly

acidic pH, it has a low percentage of organic matter, the content of

phosphorus and calcium in the soil is high; however, potassium and

magnesium are low, which indicates that to achieve optimal productions

it will be necessary to supply them with additional applications of

nutrients to the soil, according to the needs of the crops.

Fertilization was carried out with nitrogen at the time of sowing at a rate of 50 kg ha-1 and 100 kg ha-1

of potassium, using urea and potassium chloride as carriers,

respectively, it was not fertilized with phosphorus because the content

in the soil it was high (Table 1).

The preparation of the soil and the sowing was carried out as recommended in the Technical Guide for the corn crop 15, establishing the hybrid HST-3235 at three planting distances (Table 2).

Table 2.

Identification and description of treatments

| Treatments | Description (Seeding Density to use) |

|---|

| 1 | Control (0.90 x 0.30 m with 2 grains by nest) |

| 2 | 0.90 x 0.25 m with 1 grains by nest |

| 3 | 0.90 x 0.25 m with 2 grains by nest |

The surface of the experimental unit was 6 x

5.4 m, spaced 1 m wide. The management of the weeds (weeds) was carried

out mechanically and manually on a weekly basis. The experiments were

conducted under a randomized block design with three replications and

three treatments.

Irrigation was by sprinkler

with a spacing of 12 x 12 m. The irrigation regime (exploitation) was

with constant interval and variable norm, Table 3 shows some irrigation data.

Table 3.

Norm applied according to space to 3.0 BAR

| Number of irrigation | Date | Time of irrigation (hours) | Norm applied according to space to 3,0 BAR |

|---|

| (mm) | (m3 ha-1) |

|---|

| 1 | 1st tenth/December/2018 | 1 | 15 | 146,5 |

| 2 | 2nd tenth/December/2018 | 2 | 29 | 293 |

| 3 | 3th tenth/December/2018 | 2 | 29 | 293 |

| 4 | 1st tenth/January/2019 | 2 | 29 | 293 |

| 5 | 2nd tenth/January/2019 | 2.5 | 37 | 366,2 |

| 6 | 3th tenth/January/2019 | 2.5 | 37 | 366,2 |

| 7 | 1st tenth/January/2019 | 2.5 | 37 | 366,2 |

Note: 1 mm of the cape of water be equivalet to 10 m3 ha-1

The methodology used to determine the number

of plants per surface, was from the average distance between the plants

in various points of the field to guarantee representativeness, it was

multiplied by the distance of the median. This provides the area

occupied by each plant, having the total area of the field; this is

divided by that used by a plant, thus giving the number of plants on the

surface 16.

No. of plants = Sn / n x c

The variable evaluated was the yield (t ha-1).

The sowing depth (cm) was also determined to know how the emergence of

the plants influenced this variable. At different points of the

experiment, the soil was removed until the plant was discovered and it

was measured with a millimeter ruler from the mesocotile to the last

leaf and the plant height (m). It was measured from the base of the stem

to the last node where the flower is inserted, the average was taken

for each plot, 70 days after emergence, 30 plants were taken at random,

within the useful plot. The data obtained were statistically processed

and analyzed, using the double classification analysis of variance and,

when necessary, Duncan's multiple range test was performed at 5 %

probability.

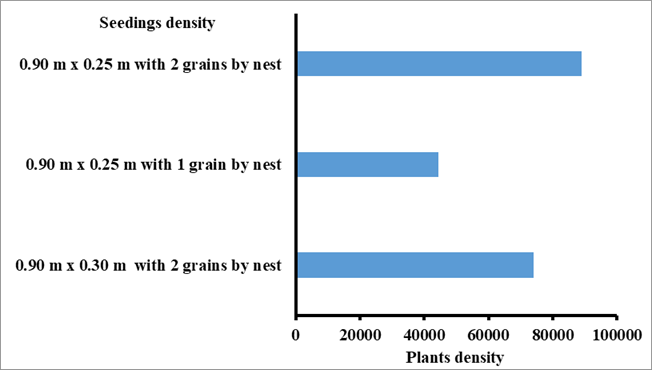

Comparison of planting densities

A count of total plants at harvest was made to determine the plant density (Figure 1).

The individual analysis by planting density had significant differences

with respect to plant density. The best treatment was planting density

0.90 x 0.25 m with two grains per nest, with a plant density of 88 888,

being significantly different from the other two densities of 74 074 and

44 444 plants ha-1.

Figure 1.

Plant densities as a function of planting densities

The relationship between grain production

and population density is complex, since the best response in grain

yield varies according to the condition of the soil, climate, cultural

practices and genotype 5. The International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) suggests optimal stocking densities of 65,000 plants ha-1 for tropical maize genotypes with a plant height greater than 2.4 m 8.

Studies carried out on population densities in maize hybrids, under

seasonal conditions in the humid tropics, showed that by increasing the

density from 50,000 to 62,500 plants ha-1, an increase in grain yield of 0.30 t ha-1 was obtained 9. It has also been reported that the yield increased 0.6 t ha-1, by increasing the population density from 60,000 to 70,000 plants ha-1 (10.

Several studies report differences in the response of maize to

population density, depending on the genotype and environmental

conditions 11, results that coincide with those obtained.

Table 4 shows the yield of corn in

young cobs and in grains. The consumption of corn in Cuba is generally

done when the grains are in their "tender" state. This method has the

advantage of freeing the surface before the end of the crop cycle and

allows to advance the entry of the new crop and, with it, the

coefficient of rotation 17 is raised.

Table 4.

Yield of young corn (cobs) and grains (t ha-1)

| Treatments | Yield of tender corn (t ha-1 ) |

|---|

| Ear of corn | grains |

|---|

| 0.90 x 0.30 m with 2 grains by nest | 9.619 b | 3.237 b |

| 0.90 x 0.25 m with 1 grains by nest | 7.223 c | 3.112 c |

| 0.90 x 0.25 m with 2 grains by nest | 11.800 a | 4.971 a |

The means followed by different letters, in the column, for each

variable in joint analysis, differ from each other with the significance

level of 0.05 probability, according to Duncan's test (1955). ***

P˂0.001

With respect to the sowing distances 0.90 x

0.30 m with 2 grains per nest and 0.90 x 0.25 m with 2 grains per nest.

The answer was in correspondence with what was stated by what was

raised (18), when indicating as successful productions of young cobs,

above 9 t ha-1; not being so for 0.90 x 0.25 m with 1 grain per nest.

The

production of green beans without bracts (49 %) and corncob (34 %)

corresponds to the expected results, since there is a coincidence with

the production of cobs. Furthermore, it coincided with the range of

production normally obtained in Cuba, for the green grain production

indicator 19,20, which is considered good if grain production is above 3.5 t ha-1;

the yield obtained was in correspondence with those achieved in other

investigations, where a maize hybrid with different planting densities

was used 15.

The grain yield ranged between 3, 112 and 4,971 t ha-1.

The highest yield of grain and cobs was obtained with 0.90 x 0.25 m

with 2 grains, when compared with the production control most used in

productions; while the lowest yield was presented with the density 0.90 x

0.25 m with 1 grain per nest.

On the other hand,

the height of the cob varied between 0.92 and 1.23 m, which could be in

correspondence with the depth of sowing that was not uniform (Figure 2), which caused that all the seedlings did not emerge at the same time as shown in Figure 3.

The

treatments with the highest population densities were those that showed

the highest height of the upper cob (AMS), this indicator shows great

importance, since the height of the cobs can make manual harvesting

difficult if it is very high. In addition, it is more prone to lodging,

due to the weight that the stem supports 21;

therefore, in this case it is good to select the treatments that are

lower in height of the upper cob or that have a good relationship with

the height of the plant. By relating the height of the upper cob with

the plant height, it can be argued that the height of the plant is a

parameter that depends largely, on external factors of the environment.

In this sense, treatments with the highest plant height have the

shortest distances between them and the highest number of plants per

nest, which increases density and causes greater growth 22.

It

is worth noting that in the variable no significant differences were

found between the treatments. The result shows that at low planting

densities, the corn plants had less competition for water and nutrients

and vice versa, thus they grow in search of sunlight, in this way equal

in height to the plants that were planted at low densities.

With the density of 88 888 plants ha-1,

the highest height was reached. Related to this, other authors mention

that the plant height is a parameter that depends, largely, on external

factors of the environment 22.

In this sense, the treatments with the highest plant height have the

shortest distances between plants and the highest number of plants per

nest, which increases the density and this causes greater growth.

Figure 2.

Sowing depth at different points of the experiment (cm)

The amount of water that the crop received

during its development was 550 mm, as a result of the rainfall recorded

during the development of the crop (337 mm) and the irrigation applied

(213 mm), which is within the appropriate interval (500 at 1 000 mm) for

cultivation of maize in the humid tropics 23. Under conditions of the present study, the increase in density from 44,444 to 88,888 plants ha-1

increased grain yield by 50 %. This increase was similar to that found

in other studies, in which increases in grain yield were observed at

densities greater than 50,000 plants ha-1 (10,24.

Figure 3.

Influence of planting depth on seedling height after emergence

Despite the fact that the height of the plant and the cob height were higher than those mentioned in other studies 25; the increase in population density was similar to that reported by other authors 26,27.

An

increase in yield was obtained at a higher population density, so it is

suggested to take into account, for other studies, the population

density of 88 888 plants ha-1 for the hybrid HST-3235; from this it is inferred that it can support higher population densities.

The

highest yields of the HST-3235 hybrid are obtained with a planting

frame of 0.90 x 0.25 m with 2 grains per nest and a planting density

that ranges between 74-88 000 plants ha-1.

The sowing depth influenced the emergence of the corn seedlings, so they did not all emerge uniformly.