INTRODUCCIÓN

El frijol común (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) constituye uno de los platos fundamentales en la dieta de la población cubana, donde se consume casi diariamente con un estimado del consumo per cápita de 9 kg por año. Esta leguminosa constituye uno de los platos típicos de la población 1. Además, este grano se considera como un cultivo estratégico, por sus propiedades nutricionales (fuente significativa de proteínas, vitaminas, minerales y fibra dietética), su presencia en los cinco continentes y su importancia en el desarrollo de la economía campesina, entre otros atributos, además de ser una fuente alternativa de proteína más barata que la carne y componente esencial de una dieta saludable 2,3.

Las condiciones edafoclimáticas en Cuba son favorables para el cultivo del frijol pero los últimos informes nacionales indican que en 2016 se produjeron 272728 toneladas, distribuidas principalmente en dos formas productivas (sector estatal y sector no estatal), lo cual no satisface la demanda nacional y los rendimientos medio alcanzados no sobrepasan las 1,3 t ha-1 (4, cifras inferiores a los potenciales alcanzados por los cultivares comerciales que no satisfacen la demanda nacional, por lo que se requiere acudir a las importaciones, lo que pone en riesgo la seguridad alimentaria de la población.

Por estas razones, en enero del 2012, durante el VI Congreso del PCC, se aprobó una estrategia, dentro de los Lineamientos de la Política Económica y Social, para asegurar el incremento de la producción de frijol, con el fin de sustituir, gradualmente, las importaciones de este grano. Esa política de desarrollo hace mención a los diversos desafíos a los que los productores e investigadores de este cultivo deben enfrentarse.

En Cuba se siembra frijol en todo el territorio nacional, con diferencias entre los sistemas productivos, en cuanto a tipo de suelo, acceso de los productores a los insumos agrícolas, entre otros aspectos. Además del contraste regional, existe una interacción genotipo ambiental, dado que, dentro del período considerado para siembra de esta especie, que varía entre los meses de septiembre a enero 1, existen diferencias en el comportamiento de las variables climáticas (temperatura y precipitaciones, fundamentalmente), las que determinan la respuesta agronómica de cada cultivar y el rendimiento final en grano, por lo que se requieren cultivares adaptados a este escenario productivo.

Entre los cultivares comerciales de grano rojo se destaca, por su empleo en la producción, ‘Velasco Largo’, de grano grande (masa de 100 granos mayor de 40 g), porte erecto (tipo I) y ciclo corto, por lo que es preferido en muchas regiones del país, pero es muy susceptible a la mayoría de las enfermedades fitopatógenas que afectan el cultivo en Cuba. Igualmente, ‘Guama 23’ y ‘Rubí’, tienen un tamaño de grano grande y hábito de crecimiento tipo I y II, respectivamente, pero son menos conocidas y susceptibles ante el virus del mosaico dorado del frijol. Entre los cultivares de grano pequeño, destacan la ‘Cuba Cueto 25-9R’, ‘Buena Ventura’ y ‘Delicia 364’, el primero, susceptible a los principales patógenos que presenta el cultivo y las otras dos con mejor respuesta en campo ante las enfermedades, pero de grano pequeño y reacción intermedia ante la roya, enfermedad de gran importancia para las siembras tardías. El cultivar ‘CIFIG 110’ es de más resiente liberación, aún poco conocido, aunque parece el más promisorio por su caracterización agronómica, según se informa en la guía técnica para la producción de frijol, pero aparece con respuesta intermedia ante la roya 1, por lo que se requieren cultivares adaptados con buena respuesta agronómica en los diferentes escenarios productivos y que tengan aceptación campesina.

El objetivo de este trabajo fue evaluar el rendimiento, la adaptación entre épocas de siembra y la aceptación campesina del nuevo cultivar de frijol de grano rojo ‘Odile’.

MATERIALES Y MÉTODOS

Material Vegetal

El material vegetal utilizado en los diferentes ensayos fue variable. Solo se muestran los resultados de dos cultivares comerciales de color de grano rojo que están muy diseminados en el territorio nacional, uno de color crema y dos de color de grano negro que fueron los que coincidieron en todos los ensayos. Así también se incluyó el nuevo cultivar ‘Odile’, de color de grano rojo (Tabla 1).

Tabla 1.

Cultivares empleados para el análisis de la estabilidad entre momentos de siembra del nuevo cultivar ‘Odile’

IIGranos (Instituto de Investigaciones de Granos ); INIFAT (Institutito de Investigaciones Fundamentales en Agricultura Tropical “Alejandro de Humboldt”), INCA (Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Agrícolas)

Análisis de la estabilidad del rendimiento del nuevo cultivar de frijol ʻOdileʼ

Para el análisis de la estabilidad del rendimiento del nuevo cultivar de frijol ʻOdileʼ se desarrollaron cuatro experimentos en diferentes momentos de siembra, 8 de septiembre de 2016, considerado como época temprana, 11 de noviembre de 2016, momento que se considera como época óptima, 20 de enero de 2017 considerada como época tardía. Estos experimentos se realizaron en la finca del área central del Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Agrícolas (INCA) y el 23 de enero de 2017 se montó otro ensayo en el área de producción de la finca “El Mulato”, perteneciente a la Cooperativa de Créditos y Servicios Fortalecida (CCSF) “Orlando Cuellar”. Este último se muestra en promedio con el del 20 de enero.

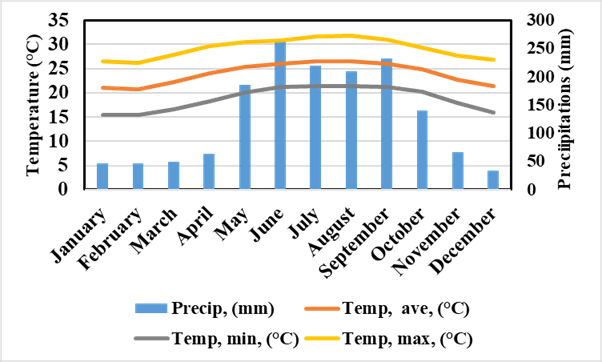

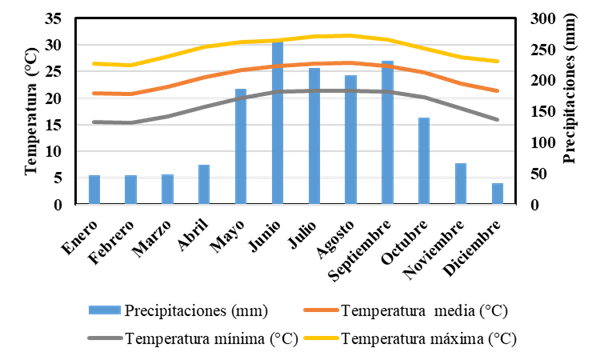

Ambas áreas donde se desarrollaron los experimentos están situadas en la localidad Tapaste, municipio San José de las Lajas, en la provincia Mayabeque, con una altitud de 122 m s.n.m. y un suelo clasificado como Nitisol ferralítico líxico 5. En la Figura 1 se muestra el comportamiento histórico de las precipitaciones y temperatura de la región 6.

Figura 1.

Régimen pluviométrico y temperaturas históricas en la región donde se realizó el estudio

La preparación de suelo y las atenciones culturales en ambas áreas se realizaron según lo establecido en la guía técnica para el cultivo del frijol en Cuba 1, con la particularidad de que en el INCA fue de forma mecanizada y en la finca “El Mulato” las hileras (surcos) se realizaron con tracción animal.

La distancia de siembra en el INCA fue de 0,75 cm entre hileras y en la finca “El Mulato” de 0,60 m. La distancia entre plantas fue de 0,08 m para un promedio de 12 semillas por metro lineal en “El Mulato” y 0,06 m, para un promedio de 16,6 semillas por metro lineal en el INCA.

Variables evaluadas

Las variables que se tuvieron en cuenta fueron: la respuesta ante la incidencia natural del virus del mosaico dorado amarillo del frijol (BGYMV), por sus siglas en inglés Bean golden yellow mosaic virus; bacteriosis común (Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. phaseoli) y roya del frijol (Uromyces appendiculatus) (enfermedades que se presentaron durante el desarrollo de los experimentos) y el rendimiento al 13 % de humedad (kg ha-1). Para determinar el rendimiento se tomó un metro lineal de la hilera central de la parcela y se dejó los bordes. La respuesta ante las enfermedades se evaluó por las escalas de nueve grados, para cada enfermedad, propuesta por CIAT 7, cuyos valores son: 1 a 3 es resistente, 4 a 6 intermedio y 7 a 9, susceptible.

Diseño experimental y Análisis estadísticos

En ambos casos se empleó un diseño experimental en bloques completos al azar con tres réplicas y la unidad experimental consistió en parcelas de cinco hileras y cinco metros de longitud.

Luego de comprobar los supuestos teóricos de normalidad y homogeneidad de varianza, a los datos de la reacción ante la incidencia natural de las enfermedades identificadas durante los experimentos, se aplicó un análisis de varianza de clasificación doble, con el rendimiento, se realizó un análisis combinado (época-genotipos) para conocer la interacción existente entre los factores. Ambos análisis con el uso del programa estadístico SPSS, versión 19 sobre Windows. Cuando se detectaron diferencias significativas (P≤0,05) entre tratamientos (genotipos), se aplicó la comparación de medias basada en la prueba de rangos múltiples de Tukey 0,05.

Análisis de estabilidad del rendimiento

Para el análisis de la estabilidad del rendimiento, se utilizó el Modelo de efectos principales aditivos e interacción multiplicativa (Modelo AMMI). A partir del primer componente principal y el resto de los componentes, en caso de representar un porcentaje aceptable de la interacción (60 %) con el programa Excel biplot01, se generó una Figura (biplot) para representar las similitudes de genotipos o de ambientes.

El modelo AMMI está representado por la siguiente ecuación 8:

donde:

Yij = Rendimiento del i-ésimo genotipo en el j-ésimo ambiente (época)

Los parámetros aditivos son:

μ = media general

Gi = Efecto del i-ésimo genotipo

σj = Efecto del j-ésimo ambiente

λk = Valor propio del componente principal K

αij * ɣjk = Valor del componente principal k de genotipo y época

Ɛij = Error experimental

Aceptación Campesina. Resultados de la selección participativa de variedades

Para verificar la aceptación campesina del cultivar de frijol ‘Odile’, se realizaron tres ferias de diversidad, con el uso de la metodología descrita 9, donde expusieron diferentes genotipos. Todas las ferias se efectuaron en la Finca de producción “El Mulato”.

Para la primera feria se realizó una siembra en septiembre, 2015, la segunda en enero de 2016 y la tercera siembra se hizo en noviembre de 2017. Todas las siembras fueron en parcelas experimentales formadas por cinco hileras separadas 0,60 m, a cinco metros de longitud, para un total de 15 m2 para cada material a seleccionar.

El material vegetal varió en cada una de las siembras. En la primera consistió en siete cultivares comerciales, uno precomercial (‘Velasco Largo’, ‘Cuba Cueto 25-9N’, ̒Engañador ’ (BAT 93), ̒Chevere’, ̒ICA PIAJAO’, ‘M 112’ y ‘CUT 53’) y seis líneas experimentales provenientes del Centro Internacional en Agricultura Tropical (CIAT) y del programa de investigación (PIF) en frijol, en Honduras (‘SCR 16’, ‘SCR 21’, ‘SCR15’, ‘SCR 3’, del CIAT y ‘X0104-45-5-1-4’, ‘X069157-14-4-5-5’, ‘X0104-52-5-5-3’ del PIF). En la segunda feria, los materiales utilizados fueron ‘SEN 81’, ‘SEN 74’, ‘SCR 5’, ‘SEN 95’, selección de ‘SCR 15’ (‘Odile’) del CIAT; ‘SURU’, ‘RBF 15-70’, ‘XRAV 40-4’, ‘MHN 322-49’ del PIF y ‘Cuba Cueto 25-9N’, ‘ICA PIJAO’ y ‘BAT 93’ cultivares comerciales. En la tercera siembra el material vegetal fue de 23 cultivares que están en la producción comercial en Cuba, que incluían al cultivar ‘Odile’ 10.

Cuando los genotipos estaban en la etapa R8 (madurez fisiológica), se invitó a agricultores de cooperativas agropecuarias del territorio para participar en una feria de diversidad. Participaron 13, 28 y 26 agricultores, para las siembras de septiembre, noviembre y enero, respectivamente.

Los genotipos solo tenían un número y a cada agricultor se les dio una boleta para seleccionar hasta cinco materiales de los expuestos en la feria. Cada material tenía una muestra de las semillas para que se observara el color, el tamaño y la forma de los granos.

Se determinó el porcentaje de selección de los diferentes genotipos y se verificó la relación existente con el color del grano, dado que este es un criterio importante en el comercio de los frijoles en Cuba. Este estudio se hizo a través de un análisis de proporciones de X2 de los diferentes materiales mostrados con el paquete estadístico SPSS versión 19, sobre Windows.

RESULTADOS Y DISCUSIÓN

En la Tabla 2 se puede apreciar el resultado del análisis de varianza del rendimiento de los genotipos estudiados a lo largo de las épocas de siembra temprana, óptima y tardía. Se pudo apreciar diferencias estadísticas entre los ambientes, representado en este estudio por las épocas de siembra, asimismo entre los genotipos y la interacción de los dos factores (genotipo*ambiente). Ello indica que estas épocas constituyen ambientes diferentes para la siembra del frijol en Cuba, lo que muestra la existencia de interacción genotípica por la variabilidad ambiental existente entre los momentos de siembra en estudio.

Tabla 2.

Análisis de varianza del rendimiento de seis genotipos de frijol común en diferentes momentos de siembra (8 de septiembre de 2016, 11 de noviembre de 2016, 20 de enero de 2017 y el 23 de enero de 2017)

*** (significativo al 0,001 de probabilidad respectivamente), ns (no significativo para p≤0,05)

Tal variabilidad se atribuye, principalmente, a las diferencias en las precipitaciones ocurridas durante el desarrollo del frijol y las temperaturas, que son superiores en el momento de la siembra de septiembre, que es el segundo mes, después de junio, de mayores precipitaciones en esta localidad (Figura 1).

Este resultado indica, que en el programa de mejora genético, se debe tener en cuenta este aspecto para la obtención de variedades adaptadas al periodo recomendado (septiembre-enero) para la siembra de frijol o con adaptación específica a cada uno de los momentos recomendados. En este sentido varios autores han identificado una respuesta agronómica diferente entre cultivares de frijol, al ser sembrados en diferentes ambientes donde el régimen hídrico es diferente 11, este aspecto determina el rendimiento en muchas regiones productoras de esta especie y determina la incidencia de otros factores como las plagas 12.

Es por ello que, para la formación de nuevos genotipos, se requiere evaluar los materiales genéticos en diferentes ambientes y medir su interacción genotipo-ambiente (G x A), la cual da una idea de la estabilidad fenotípica de los genotipos ante las fluctuaciones ambientales y es necesario para el desarrollo de un programa de mejoramiento genético 13.

Las diferencias del rendimiento para las épocas (Tabla 3), corroboraron que el momento óptimo de siembra de frijol es noviembre, donde se obtuvo los mejores rendimientos, que difieren significativamente de los obtenidos con las siembras de septiembre y enero. Esta información está en concordancia con lo informado anteriormente por otros autores 1, que han desdoblado el periodo de siembra temprano, óptimo y tardío, así como las recomendaciones de cada uno de ellos en función del acceso que tengan los agricultores al riego.

Tabla 3.

Rendimiento promedio por época de siembra de seis genotipos de frijol común

| Época | Rendimiento |

|---|---|

| Septiembre | 1501,15 b |

| Noviembre | 2165,28 a |

| Enero | 1582,59 b |

| p | 0,011* |

Medias con letras iguales no son estadísticamente diferentes (Tukey, 0,05)

Estos resultados justifican la evaluación de cada nuevo cultivar, en las diferentes épocas, como es el caso del cultivar ‘Odile’, del cual se debe conocer si es de amplia adaptabilidad o de adaptación especifica dentro del periodo septiembre-enero.

En la Tabla 4 se muestran los rendimientos promedio que obtuvieron cada uno de los genotipos empleados en el ensayo comparativo. Se puedo apreciar que el rendimiento osciló entre 605,7 y 2643,1 kg ha-1. El cultivar ‘Odile’ fue el que mayor rendimiento promedio produjo (2643,1 kg ha-1) sin diferencias estadísticas con ‘Delicia 364’ (1938,7 kg ha-1), ‘CC25-9N’ (1695,8 kg ha-1) y ‘BAT-93’ (2063,6 kg ha-1). Esta respuesta agronómica justifica su introducción en la producción, ya que su rendimiento es superior a cultivares que son altamente demandados en la actualidad, dado fundamentalmente por su alto potencial de rendimiento, adaptabilidad y resistencia a plagas 1,14,15, así mismo, es válido destacar que en evaluaciones anteriores 14, donde se icluyó el cultivar ‘Odile’ y algunos de estos cultivares comerciales utilizados en este estudio, se evidenció la existencia de variabilidad, lo que constituye un aspecto importante en los programas de mejora genética 16,17.

Tabla 4.

Rendimiento promedio seis cultivares de frijol común en tres épocas de siembra y dos ambientes de un ensayo comparativos de adaptación y rendimiento entre épocas de siembra

| Cultivares | Rendimiento (kg ha-1) |

|---|---|

| ‘Delicia’ | 1938,7 a |

| ‘Velasco Largo’ | 605,7 c |

| ‘Cuba Cueto’ 25-9N’ | 1695,8 ab |

| ‘Engañador (BAT 93)’ | 2063,6 ab |

| ‘Odile’ | 2643,1 a |

| ‘ICA PIJAO’ | 1550,9bc |

| CV | 44,68 |

| p | 0,000*** |

Letras distintas significan diferencias significativas para prueba de Tukey p≤0,05; *** significativo para p≤0,0001

Respuesta ante enfermedades

La respuesta ante enfermedades de los diferentes cultivares comparados en este estudio se muestran en el la Tabla 5. Se pudo apreciar que los sistemas patogénicos que se manifestaron durante los diferentes momentos de siembras fueron: Bacterisis común (Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. phaseoli), el virus BGYMV (por sus siglas en ingles Bean golden yellow mosaic virus) y la roya (Uromyces appendiculatus). Estos patógenos son de gran importancia en la producción de este grano en la región donde se realizó este estudio 14,18,19) y sus implicaciones pueden ser catastróficas, con pérdidas importantes en la producción, ya que cada día se identifican fuentes genéticas diferentes dentro de estos patógenos, que pueden ser más agresivas sobre el cultivo 18, lo que deriva la importancia de obtención de resistencia como alternativa económica, social y ambientalmente viable para el manejo integrado de plagas.

Tabla 5.

Respuesta ante la incidencia natural de las enfermedades que manifestaron seis cultivares de frijol común durante tres momentos de siembra

BGYMV= virus del mosaico amarillo dorado del frijol. Bc= Bacteriosis común. Letras distintas significan diferencias significativas para prueba de Tukey p≤0,05. ***Significativo al 0,001

Se muestran resultados promedios de la evaluación por medio de las escalas de nueve grados, para cada enfermedad, propuesta por CIAT (7) cuyos valores son: 1 a 3 es resistente, 4 a 6 intermedio y 7 a 9, susceptible

La enfermedad que mayor severidad mostró fue la roya (promedio 4,2) en siembras de enero, seguida del BGYMV en la siembra de septiembre (promedio 4,1) y de la bacteriosis común (Bc), en la siembra de septiembre (promedio 3,6). Así mismo, se detectó que tanto BGYMV como Bc se manifestaron en todos los momentos de siembra; sin embargo, la roya solo se presentó en las siembras de enero, al parecer ello está relacionado con las condiciones climáticas que requiere este patógeno para desarrollarse, las cuales persisten en esta época como se aprecia en la Figura 1.

El cultivar ʻOdileʼ mostró muy buena respuesta ante los patógenos que se manifestaron, donde se destacó por su reacción de resistente ante la roya, al no detectarse síntomas visibles de la enfermedad en las siembras que se realizaron en enero, al igual que el cultivar ʻBAT 93ʼ que es frecuentemente utilizado como testigo resistente a este patógeno 14. Asimismo, ante el BGYMV, tuvo buena respuesta, según la escala del CIAT 7, con reacción de resistente (entre 1,3 y 1,7 valor de la escala de 9 grados) sin diferencias estadísticas con ʻDelicia 364ʼ, cultivar que ha sido informado como resistente y con la presencia del gen bgm-110 que le confiere resistencia a esta plaga.

El cultivar ʻOdileʼ fue la que menor incidencia mostró ante Bc entre todos los cultivares que estaban en el ensayo comparativo, lo que evidencia su buena respuesta ante estos sistemas que tanto afectan la producción de esta leguminosa en Cuba y el trópico húmedo en general 11.

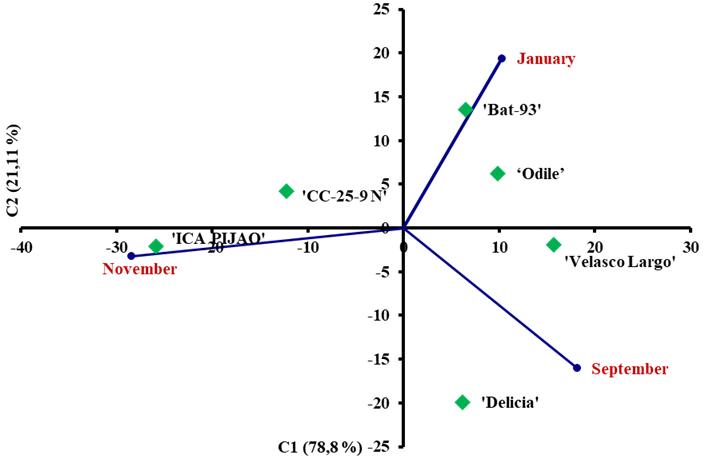

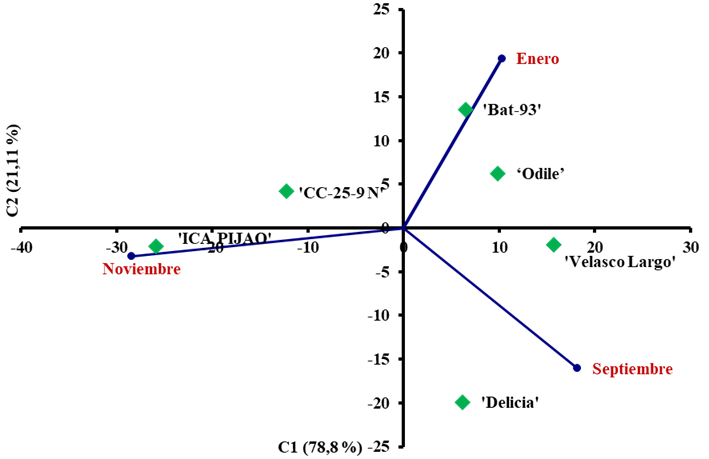

En la Figura 2 se muestra la representación biplot del análisis de varianza para el modelo AMMI, de la variable rendimiento, en los seis genotipos evaluados en la prueba comparativa. En la primera componente se explica el 78,8 % de la varianza total y el segundo componente mostró el 21,11 %. Se diferencian bien los tres ambientes y se aprecia que hubo adaptación específica de los genotipos en estos ambientes.

Figura 2.

Representación biplot de la asociación de seis cultivares de frijol común con las épocas de siembra particulares, respecto a los dos primeros ejes de componentes principales del análisis AMMI del rendimiento evaluado en tres épocas de siembra

El cultivar ‘BAT-93’ se destacó con alta adaptabilidad a la época de siembra de enero (tardía), lo que está en concordancia con la respuesta que muestra este cultivar ante la roya (Tabla 5), que es la enfermedad que más se manifiesta en esta época. El cultivar ‘ICA PIJAO’ muestra mayor adaptación a la época óptima (siembras de noviembre) y el cultivar ‘Delicia 364’ para la época de septiembre, estando en concordancia con la reacción ante BGYMV. Sin embargo, los cultivares ‘Odile’ y ‘CC25-9N’ mostraron mayor estabilidad del rendimiento entre épocas, lo que corrobora el uso de estos genotipos en la localidad de Tapaste, en cualquiera de los momentos de siembras recomendados para este cultivo.

Aceptación del cultivar ‘Odile’ en el escenario productivo de Tapaste, San José de las Lajas

En las Tablas 6, 7 y 8, se presentan los resultados de la selección participativa que se efectuó en materiales que fueron sembrados en septiembre de 2015, enero de 2016 y noviembre de 2017. Se pudo apreciar una alta aceptación de la diversidad mostrada en las tres ferias. La diversidad efectiva (porcentaje de genotipos seleccionados) fue de 92,85 %, 83,33 y 82,60 % para las siembras que se realizaron en septiembre de 2015, enero 2016 y noviembre de 2017; respectivamente.

Tabla 6.

Porcentaje de selección efectuado por agricultores de los cultivares de frijol común sembrados en septiembre de 2015

NA (número de agricultores), R (rojo), B (blanco); C (crema); N (negro); ns: no significativo para p≤0,05

Tabla 7.

Porcentaje de selección efectuados por agricultores de cultivares de frijol común sembrados en noviembre de 2017

NA (número de agricultores), R (rojo), B (blanco); C (crema); N (negro) ns: no significativo para p≤0,05

Tabla 8.

Porcentaje de selección efectuados por agricultores de los cultivares de frijol común sembrados en Enero de 2016

NA (número de agricultores), R (rojo), B (blanco); C (crema); N (negro)

Asimismo, se pudo apreciar, al analizar la aceptación por parte de los seleccionadores según el color del grano, que en la feria que se efectuó en septiembre de 2015, los cultivares de color de grano negro fueron más seleccionados con un 63,33 % y los rojos, blancos y crema en un 36,74 %, sin diferencias estadísticas entre ellos (Tabla 6), criterio que concuerda con los gustos culinarios de la población cubana 15, que mayoritariamente consumen, en mayor cuantía, los frijoles de grano negro y se ajustan más al acceso de los ingredientes necesarios para su preparación.

En la feria efectuada en noviembre de 2017, los cultivares de color negro fueron seleccionados en un 38,49 %, los rojos 21,43 % y los blancos y cremas 3,57 % sin diferencias estadísticas entre ellos y con la misma tendencia de los genotipos sembrados en septiembre (Tabla 7).

Sin embargo, en la feria efectuada en enero de 2016 los cultivares de color de grano blancos y rojos fueron los más seleccionados con 79,0 %, respecto a los negros (58 %), sin diferencias estadísticas entre ambos grupos (Tabla 8).

Aun cuando la tendencia fue de mayor selección para los frijoles de grano negro, entre los genotipos sembrados en septiembre y noviembre, el nuevo cultivar ‘Odile’ fue altamente seleccionado con 100 y 96,43 %, respectivamente, en esas ferias. Así mismo, en las siembras de enero, la selección fue de un 96,31 %. Estos resultados muestran la alta aceptación por parte de los agricultores dado que, en general, más del 96 por ciento de los seleccionadores prefieren este nuevo cultivar ‘Odile’.

Con este criterio se hace evidente que este nuevo cultivar puede tener éxito en la zona productora de Tapaste, dado su mayor estabilidad del rendimiento respecto a los demás cultivares comerciales con los que se comparó en las diferentes épocas en que se siembra el frijol en Cuba, así como el criterio de los agricultores que representan el sector no estatal, donde más se produce este grano de alta presencia en la cultura culinaria cubana.

CONCLUSIONES

El nuevo cultivar ‘Odile’ presentó buena respuesta agronómica, expresando un rendimiento superior a las 2000 kg ha-1 y estabilidad entre épocas, lo que justifica su extensión/generalización.

El cultivar ‘Odile’ presentó alta aceptación campesina, con porcentaje de selección superior al 96 % asociado a su respuesta agronómica.