Rhizobia evaluation and the use of AMF in soybeans (Glycine max (L.) Merrill)

Main Article Content

Abstract

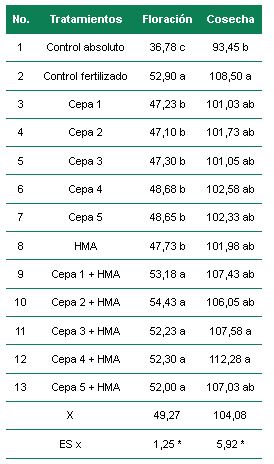

The experiment was developed under field conditions on a Lixiviated Red Ferralitic soil in the central experimental area of the National Institute of Agricultural Sciences, in order to evaluate strains of rhizobia and a strain of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, on the growth and development of the soybean cultivar INCAsoy-27, sown in summer. For this, a randomized block design was used with four repetitions per treatment, which consisted of the inoculation of microorganisms, in their simple forms and the combination of each rhizobium strain with the arbuscular mycorrhiza used, as well as two control treatments, absolute and with mineral fertilization. Results showed a positive effect of the use of the different strains of rhizobia on the growth and yield of the soybean cultivar evaluated, with similar results between them and increases in yield in relation to the absolute control between 11.01 and 14.68 %, those that were made higher when both biofertilizers were co-inoculated (between 31.19 and 38.53 % in relation to the absolute control and between 13.49 and 19.84 % in relation to the fertilized control), with little significant differences between them, regardless of the rhizobium strain evaluated. These results demonstrate the synergistic and beneficial effects of rhizobia- arbuscular mycorrhizal co-inoculation in this culture.

Article Details

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Those authors who have publications with this journal accept the following terms of the License Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0):

You are free to:

- Share — copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format

- Adapt — remix, transform, and build upon the material

The licensor cannot revoke these freedoms as long as you follow the license terms.

Under the following terms:

- Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use.

- NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes.

- No additional restrictions — You may not apply legal terms or technological measures that legally restrict others from doing anything the license permits.

The journal is not responsible for the opinions and concepts expressed in the works, they are the sole responsibility of the authors. The Editor, with the assistance of the Editorial Committee, reserves the right to suggest or request advisable or necessary modifications. They are accepted to publish original scientific papers, research results of interest that have not been published or sent to another journal for the same purpose.

The mention of trademarks of equipment, instruments or specific materials is for identification purposes, and there is no promotional commitment in relation to them, neither by the authors nor by the publisher.

References

Falconi-Moreano IC, Tandazo-Falquez NP, Mora-Gutiérrez MC, López-Bermúdez FL. Evaluación agronómica de materiales de soya (Glycine max. (L)Merril) de hilium claro. RECIAMUC. 2017;1(4):850-60. doi:10.26820/reciamuc/1.4.2017.850-860

Ghani M, Kulkarni KP, Song JT, Shannon JG, Lee J-D. Soybean Sprouts: A Review of Nutrient Composition, Health Benefits and Genetic Variation. Plant Breeding and Biotechnology. 2016;4(4):398-412. doi:10.9787/PBB.2016.4.4.398

FAO. Estadísticas mundiales de producción de soya [Internet]. 2018 [cited 08/11/2021]. Available from: https://blogagricultura.com/estadisticas-soya-produccion/

Departament of Agriculture(USDA). World Agricultural Outlook Board [Internet]. 2018 [cited 08/11/2021]. Available from: https://www.usda.gov/oce/commodity-markets/waob

Sembralia - Cefetra Dijital Services. ¿Que son los bioestimulantes agrícolas y cómo pueden ayudarte? [Internet]. 2023 [cited 08/11/2021]. Available from: https://sembralia.com/blogs/blog/bioestimulantes-agricolas

Delgado H. Análisis de la combinación de microorganismos bioestimulantes (Micorrizas y Rhizobium) en el cultivo de soya (Glycine max). Universidad Técnica De Babahoyo [Internet]. 2019; Available from: http://dspace.utb.edu.ec/handle/49000/6129

Ibiang YB, Mitsumoto H, Sakamoto K. Bradyrhizobia and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi modulate manganese, iron, phosphorus, and polyphenols in soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merr.) under excess zinc. Environmental and Experimental Botany. 2017;137:1-13. doi:10.1016/j.envexpbot.2017.01.011

Hernández-Jiménez A, Pérez-Jiménez JM, Bosch-Infante D, Speck NC. La clasificación de suelos de Cuba: énfasis en la versión de 2015. Cultivos Tropicales [Internet]. 2019;40(1). Available from: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?pid=S0258-59362019000100015&script=sci_arttext&tlng=pt

Fernández F, Gómez R, Vanegas LF, Martínez MA, de la Noval BM, Rivera R. Producto inoculante micorrizógeno. Oficina Nacional de Propiedad Industrial. Cuba, Patente. 2000;22641.

Rodríguez-Yon Jy, Arias-Pérez L, Medina-Carmona A, Mujica Pérez Y, Medina-García LR, Fernández-Suárez K, et al. Alternativa de la técnica de tinción para determinar la colonización micorrízica. Cultivos Tropicales. 2015;36(2):18-21.

Trouvelot A, Kough JL, Gianinazzi-Pearson V. Mesure du taux de mycorhization VA d’un systeme radiculaire. Recherche de methodes d’estimation ayant une signification fonctionnelle. Physiological And Genetical Aspects of Mycorrhizae. 1986;832.

Herrera-Peraza RA, Furrazola E, Ferrer RL, Valle RF, Arias YT. Functional strategies of root hairs and arbuscular mycorrhizae in an evergreen tropical forest, Sierra del Rosario, Cuba. Revista CENIC. Ciencias Biológicas. 2004;35(2):113-23.

Hernández AF. La coinoculación Glomus hoi like-Bradyrhizobium japonicum en la producción de soya (Glycine max) variedad Verónica para semilla. Cultivos tropicales. 2008;29(4):41-5.

Hernández M, Cuevas F. The effect of inoculating with arbuscular Mycorrhiza and Bradyrhizobium strains on soybean (Glycine max (L) Merrill) crop development. Cultivos Tropicales. 2003;24(2):19-21.

Corbera Gorotiza J, Nápoles García MC. Efecto de la inoculación conjunta Bradyrhizobium elkanii-hongos MA y la aplicación de un bioestimulador del crecimiento vegetal en soya (Glycine max (L.) Merrill), cultivar INCASOY-27. Cultivos Tropicales. 2013;34(2):05-11.

Sauvu-Jonasse C, Nápoles-García MC, Falcón-Rodríguez AB, Lamz-Piedra A, Ruiz-Sánchez M. Bioestimulantes en el crecimiento y rendimiento de soya (Glycine max (L.) Merrill). Cultivos Tropicales [Internet]. 2020;41(3). Available from: scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0258-59362020000300002

Tovar-Franco J. Incremento en invernadero de la calidad y cantidad del follaje de la alfalfa (Medicago sativa l.) variedad Florida 77 causado por la combinación de fertilización biológica y química en un suelo de la serie bermeo de la sabana de Bogotá. Universitas Scientiarum. 2006;11(Esp):61-71.

Granda-Mora KI, Alvarado-Capó Y, Torres-Gutiérrez R. Efecto en campo de la cepa nativa COL6 de Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae sobre frijol común cv. Percal en Ecuador. Centro Agrícola. 2017;44(2):5-13.

Chipana V, Clavijo C, Medina P, Castillo D. Inoculación de vainita (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) con diferentes concentraciones de Rhizobium etli y su influencia sobre el rendimiento del cultivo. Ecología aplicada. 2017;16(2):91-8.

Cantaro-Segura H, Huaringa-Joaquín A, Zúñiga-Dávil D, Cantaro-Segura H, Huaringa-Joaquín A, Zúñiga-Dávil D. Efectividad simbiótica de dos cepas de Rhizobium sp. en cuatro variedades de frijol (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) en Perú. Idesia (Arica). 2019;37(4):73-81. doi:10.4067/S0718-34292019000400073

Rivera R, Fernández F, Ruiz L, González PJ, Rodríguez Y, Pérez E. Manejo, integración y beneficios del biofertilizante micorrízico EcoMic® en la producción agrícola. INCA. Mayabeque, Cuba; 2020. 155 p.